Explore a series of interviews and reflections on the use of language by British-Nepali families living in the UK from NCW Visible Communities resident Rabi Thapa.

Read on for thoughtful considerations on the practice of languages across generations, and changing conceptions of diasporic identity, community and belonging.

This piece was commissioned as part of Rabi’s Visible Communities virtual residency.

When I first started looking into the role of language in living in the UK, I aimed to ‘translate’ the lived experience of British-Nepali Gurkha families in Brecon, a military market town in south Wales. Despite the fact that (dwindling) British Gurkha recruitment has historically drawn from half a dozen discrete ethnolinguistic groups in Nepal, the trajectories of these soldiers and their families presented to my eye a cohesiveness that illustrated the typical challenges faced by migrants to this country.

To generalise – a serving Gurkha soldier or veteran who came to the UK in the last half century might speak good Nepali and passable English, although his spouse might only have a limited grasp of English. Depending on the generation they were drawn from, both might speak the language associated with their own ethnicity – Gurung, Rai, Magar, Limbu, Tamang. Back in Nepal, they may have used this language within their community, but in the UK, dissolving within the broader Nepali diaspora, Nepali would have taken precedence alongside English. But what of their children, now twice removed from their ancestral language, struggling with Nepali, and living in English?

Khusiman Gurung, Brecon

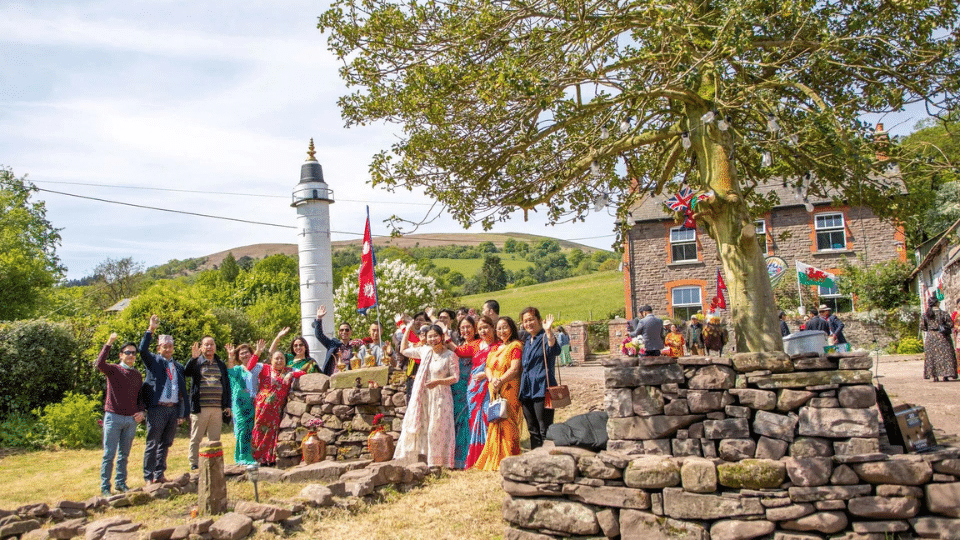

Retd. Major Khusiman Gurung, who came to the UK in the early 1980s before settling in Wales upon retirement in 2008, is one of two officer-level retirees based in Brecon. The Gurkhas are well-regarded in Brecon: in 1985, they were declared honorary citizens of the town, a “Gurkha Walk” is maintained by local veterans and their families, and there is an annual parade in the town centre. Khusiman has been here long enough to enjoy the comforts of a strong diasporic community and endure the burden of being at its centre, as the chairman of an active Gurkha organisation with 1,100 members: ‘Kunai kām hudaina khāli khāney, nāchney!’ No work gets done, it’s just eating and dancing!

But Covid-19, he says, exposed the diaspora for what it was – a loose network that could not and did not want to hold fast in the face of lockdown. With leaders reluctant to reach out to the community at large, it became clear that the Nepali diaspora could not look after its own. This failure on the part of the older generation, which had invested so much time and energy in binding Nepalis old and new, only justified the attitude of the younger generations. Caught up in education or full working lives, they simply did not have the time to spend ‘being Nepali’ outside of their homes, including lobbying for English language classes for adults and organising Nepali language classes for their children.

Perhaps this was why Khusiman decided to chance his legacy by setting up an institution that could outlive his efforts to perpetuate the culture of his homeland. In 2021, he led a campaign to raise over a million pounds from 200+ (mostly Nepali-origin) shareholders to purchase a farmhouse and 24 acres of land around it. The planned renovation and redevelopment was registered as Nepali Village UK, a multipurpose cultural centre that will eventually serve as a camping site, holiday home, visitor centre, meeting venue and meditation hall. In Khusiman’s words, ‘If we don’t celebrate and exhibit our culture, then how do we transmit it to the newer generations?’

The site certainly has commercial possibilities, tucked away as it is in the national park of Bannau Brycheinniog (latterly the Brecon Beacons), but even if it obtains planning permission (a big If), how would a development that includes a faux ancestral forest dotted with sculptures of faux Nepali identity mesh with the cultural history of a place that in rebranding itself is leaning harder into its Welsh roots? I fear that the planners will not understand Khusiman’s impassioned spiel on cultural preservation; they will not understand the language he is speaking. Or they will understand it too well, as a purely commercial concern.

The site certainly has commercial possibilities, tucked away as it is in the national park of Bannau Brycheinniog (latterly the Brecon Beacons), but even if it obtains planning permission (a big If), how would a development that includes a faux ancestral forest dotted with sculptures of faux Nepali identity mesh with the cultural history of a place that in rebranding itself is leaning harder into its Welsh roots? I fear that the planners will not understand Khusiman’s impassioned spiel on cultural preservation; they will not understand the language he is speaking. Or they will understand it too well, as a purely commercial concern.

Either way, my initial explorations around Gurkhas living in Brecon were rudely interrupted: first by a racist incident an hour south, in Merthyr Tydfil; second by the news that Khusiman (with his contact book) was travelling imminently to Nepal to tend to his gravely ill mother; and third, by an outbreak of Covid in my own household.

These sudden inconveniences, in particular the experience of being racially abused, compelled me to rethink the project and consider for the first time in a long time how I stood in relation to my own cultural identity, and what role language played in this. I decided to focus on Nepalis closer to my own experience, and close at hand.

In a certain sense, I had had it easy in the UK, where I was born. It was in Nepal that I had been presented with the problem of assimilation, after arriving at the age of six with parents who had not, ultimately, assimilated to their satisfaction. Largely lacking the language and completely unappreciative of the food, climate and myriad relatives on offer, I was dubbed ‘Englandoo’ at primary school and true to expectation, excelled in English at the expense of Nepali. When I returned to the UK in my early twenties, I simply slotted back in.

Perhaps all immigrants who struggle significantly with the native language are ‘unhappy’ in the same way. They face similar practical challenges. But what of those who may have benefited from an English-language education prior to the experience of migration? Are they all ‘happy’ in their more streamlined assimilation, or do they present with different kinds of cultural unhappiness, also linked with the use of language? To what extent does language determine who they are, and can be?

Mahendra and Cheryl Upadhyay, Machynlleth

The Nepali diaspora around where I live, between the coastal university town of Aberystwyth and the medieval capital of Wales, Machynlleth, is by no means extensive. But it does include an intriguing strain of Nepalis from the state of Assam in northeast India. My long-deceased father-in-law, Hari Upadhyay, was from Assam, and the ghosts of his past are scattered across Wales and the midlands, from Cardiff and Swansea up to Birmingham.

One such survivor is Dr. Mahendra Upadhyay of Machynlleth, a distant cousin and close friend of Hari. They travelled down from the Tezpur hills, on the banks of the Brahmaputra, first to medical college in the state capital Guwahati, then to Delhi for their first assignments, and thence to Wales in the early 1970s. While Hari returned briefly to wed Junu Dhungana, a recent medical graduate from the border town of Biratnagar in Nepal, Mahendra married a local nurse from Borth, Cheryl Parry, with whom he has three children.

Hari and Mahendra’s journey to Wales would not be considered remarkable now. My father was also a doctor who worked in England for a decade before returning to Nepal with us, like one of my mother’s brothers. Until Nepalis of other stripes began arriving in much larger numbers, there were chiefly two categories of Nepali professionals here – doctors and soldiers.

What is remarkable is the waxing and waning of language(s) in Mahendra’s life. As a child in Assam, he spoke Nepali at home and within the Nepali community, but he was conversant in Asamiya and Bengali, also Sanskrit-derived languages spoken by majority communities in the state. Mahendra and Hari studied medicine at an English-medium institute, and when they moved to Delhi upon graduation they moved without too much trouble to daily use of other related languages more prevalent in the capital, such as Hindi and Punjabi.

But the move overseas changed everything. From the melting pot of caste and creed and language that India represented, the two young doctors found themselves in a country that was 99% white and largely English-speaking (Welsh speakers were at a low of 18.9% in the 1981 census). Educated in English, they would have got along fine at work. But what happened to the linguistic multiverse in which they had existed?

Quite simply, it faded away. Then, there were far fewer immigrants from India (or Nepal). Mahendra’s Asamiya-speaking peers, who moved to the UK around the same time, were a few hours’ drive away. His closest friend was Hari, so he spoke Nepali with him and Junu, forming a close-knit linguistic community of three that endured until Hari’s untimely death in 1990.

Cheryl was from a Welsh-speaking family, so Mahendra could have learned the language and have it taught to their children alongside Nepali. But as he explained: I was worried I wouldn’t be able to keep up with the children if they learned Welsh, with their schoolwork. I wouldn’t have known what was going on! So the children attended an English-medium school, and spoke English at home. Neither Welsh nor Nepali was seen as a language for the future, not an unusual perspective for the time and the space they occupied; neither Cheryl nor Mahendra express any regret that their Welsh-Nepali-Assamese children grew up monolingual (all have since moved to England and have English-speaking children).

Mahendra converses with me in English – I’ve forgotten all my Nepali, he claims, somewhat ruefully. Over Christmas (he doesn’t celebrate Dasain or Diwali), I overheard an exchange between him and my mother-in-law. She spoke Nepali, and he spoke English. I know that he speaks regularly with his family back in Assam, in Nepali, and he still visits every couple of years. So is he content with this studied monolingualism and monoculturalism in the place he has settled in?

Vikas Newar and Sunita Pradhan, Aberystwyth

Vikas and Sunita moved to Wales from Assam a dozen years ago on a more temporary basis, because the former’s short-term contract as a software engineer for the Welsh Government, first in Delhi and then in Aberystwyth, has always been subject to renewal. Yet they have bought a house and are raising two sons here. They are also British citizens now, although when I ask them if they feel British Sunita laughs and says, ‘Not yet,’ before adding somewhat dismissively, ‘It’s just a passport, isn’t it?’ Vikas adopts a more conciliatory tone: ‘Because I’ve lived here so long I’d like to identify myself as Welsh…especially now that I see my son learning Welsh and identifying as Welsh.’

However, neither parent is learning Welsh, and they echo, decades on, Mahendra and Cheryl’s attitude towards the language within the larger British (and global) polity; they have enrolled their older son Vihan into an English-medium school, where he is learning Welsh only as a subject (apparently quite well). We wouldn’t be able to help him with his schoolwork, they repeat.

But speaking to this younger couple gave me an idea of the changing sensibility of immigrants towards their mother tongues. Vikas and Sunita are also from the Nepali diaspora in Assam, and now work and live in primarily English-speaking environments. Nonetheless, they have refused to discard the languages they were born into for the sake of children that they want to succeed in an Anglophone world.

It makes a huge difference that they are both from the same cultural stock, and that there are more Nepali and Hindi speakers in their social circle today than there were in Mahendra’s time. They speak Nepali with each other. It’s also worth noting that neither retains any linguistic traces of the language attached to their specific, shared Newar-Nepali ethnicity; Nepal Bhasa is widely spoken where Newar communities live in Nepal, but mirroring what happened to the ethnic languages of British Gurkhas once they dispersed into the Nepali diaspora abroad, the Newars who migrated to northeast India tended to lose Nepal Bhasa, bolster their Nepali, and gain the language of the host communities, be it Asamiya, Bengali or Hindi. Vikas sums it up, ‘I think you find that when you move to a different country, you have to mix with other people. There will be some mixing – some will be lost and some will be added.’

It makes a huge difference that they are both from the same cultural stock, and that there are more Nepali and Hindi speakers in their social circle today than there were in Mahendra’s time. They speak Nepali with each other. It’s also worth noting that neither retains any linguistic traces of the language attached to their specific, shared Newar-Nepali ethnicity; Nepal Bhasa is widely spoken where Newar communities live in Nepal, but mirroring what happened to the ethnic languages of British Gurkhas once they dispersed into the Nepali diaspora abroad, the Newars who migrated to northeast India tended to lose Nepal Bhasa, bolster their Nepali, and gain the language of the host communities, be it Asamiya, Bengali or Hindi. Vikas sums it up, ‘I think you find that when you move to a different country, you have to mix with other people. There will be some mixing – some will be lost and some will be added.’

Does this also apply to their children? ‘We are mentally prepared,’ Vikas chuckles. Vihan may lose some of his linguistic heritage – Asamiya, Hindi, et al – but he stands to gain English, Welsh and Nepali.

Unlike Mahendra Upadhyay, whose Nepali-Assamese-Indian identity can appear attenuated, Sunita and Vikas project their cultural and linguistic inheritance even as they engage fully in modern professions and build their lives here in Wales with their children. They may be British citizens now, but they claim to feel first Nepali, then Assamese, then Indian. It is an irony, of course, that many Nepalis from Nepal would not consider them real Nepalis.

Junu Upadhyay, Aberystwyth

One person who has managed to fit in just about anywhere, not least because of her superlative ability to pick up the language of choice, is Junu Upadhyay, my mother-in-law. Although we tease her for her occasionally idiosyncratic English, she is comfortable with Nepali, Hindi, Asamiya and Welsh as well. In short, she is more assimilated into multiple linguistic communities than we could ever hope to be.

Junu came to the UK in 1977, a year after she married Hari. Growing up in an extended household of land-owners in Biratnagar, she was familiar with the language of the farm labourers, Maithili, and learned Hindi and Sanskrit at a Nepali-medium school. These served her in good stead at Benares Hindu University, where she completed her secondary education. She is clear that being exposed to so many languages at a very early age ‘does help you grasp the sense of different languages – or at least to accept that there are other languages other than your mother tongue.’

The language of instruction at medical college in Patna was English, but many graduates from India migrating to the UK struggled with the PLAB test, the English listening comprehension test that had just been introduced for incoming doctors when Junu arrived. In fact, she has at least two close friends, both women, who failed the PLAB test repeatedly – three strikes and out – and were thereby barred from practicing in the UK. Imagine being a medically qualified doctor forced to be a housewife!

Junu passed the PLAB, spoke to Hari in Nepali, and Asamiya soon became part of her life in Swansea, where there were regular gatherings of his friends. She remembers how difficult it was at the beginning but, she laughs, ‘Automatically, somehow, it started to come.’ She adds, ‘Everyone used to gather and speak Assamese … sabai jāna lāi English boldā boldā dikka lāgyā hunthyo.’ Everybody would be sick of speaking English.

Welsh didn’t enter the picture for Junu until they moved to Aberystwyth in ’88. Still, their first daughter, Dipti, started at a Welsh-medium nursery in Swansea, which is not notably Welsh-speaking. When I ask why, Junu offers two explanations. One, that they lived close to a Welsh-speaking family with whom they were friendly. Two – and I find this really rather interesting – as they wanted to keep Nepali as the ‘home’ language, they reasoned that ‘if they sent her to an English-medium school, she would speak it there, and outside the house, and through the media, and this and that, and we thought it would be a lot more difficult to keep Nepali.’ By introducing Welsh, they felt they could keep English within bounds, and carve out a space for Nepali. Junu was also keen on knowing the local language and culture, and took lessons that proved invaluable as a travelling local paediatrician throughout mid-Wales.

Welsh didn’t enter the picture for Junu until they moved to Aberystwyth in ’88. Still, their first daughter, Dipti, started at a Welsh-medium nursery in Swansea, which is not notably Welsh-speaking. When I ask why, Junu offers two explanations. One, that they lived close to a Welsh-speaking family with whom they were friendly. Two – and I find this really rather interesting – as they wanted to keep Nepali as the ‘home’ language, they reasoned that ‘if they sent her to an English-medium school, she would speak it there, and outside the house, and through the media, and this and that, and we thought it would be a lot more difficult to keep Nepali.’ By introducing Welsh, they felt they could keep English within bounds, and carve out a space for Nepali. Junu was also keen on knowing the local language and culture, and took lessons that proved invaluable as a travelling local paediatrician throughout mid-Wales.

Both Dipti and her younger sister Jyoti went through Welsh-language education, and Junu feels vindicated by their decision. Whether the strategy to mark off the home as Nepali territory was aided by a barricade of Welsh or not, today both her daughters speak and understand Nepali to a reasonable degree, and are fluent in Welsh as well as English. ‘So many of my friends’ children don’t speak their languages, be it Nepali or Hindi or Bengali. I think they regret it now,’ she concludes. And why wouldn’t they? Language is so central to the cultural inheritance that once the children move out, and certainly once the parents pass on, they have far fewer avenues to find their way back to the festivals, the literature, the music and, finally, the homeland – if they still consider it as such.

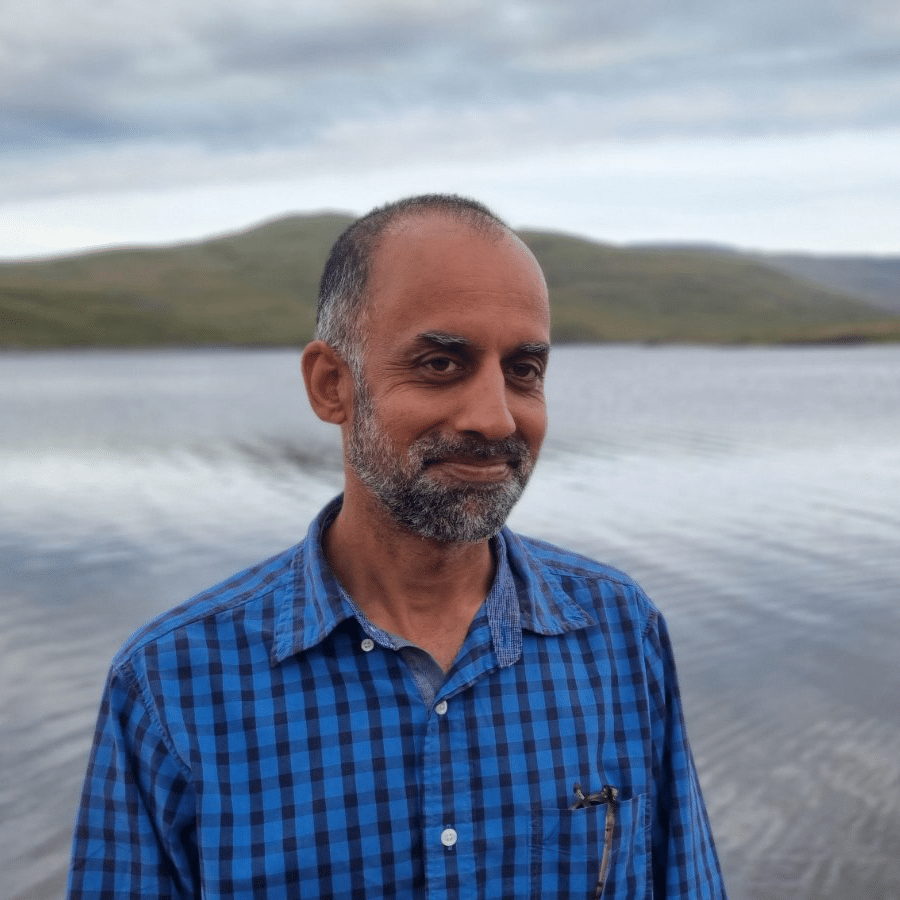

Rabi Thapa, Jyoti Upadhyay and Kian Hari Idris Thapa, Talybont

Every generation, of course, has to choose its own linguistic battles. Dipti went on to marry a Telugu-speaking Brit, but the lack of a shared language other than English is probably why their children speak neither Nepali, nor Telugu, nor Welsh. Jyoti went on to marry me, and we lived in Nepal for a decade. So though we use mostly English at home, since the arrival of Kian three years ago we have taken on clearly defined roles to advance his linguistic chops: Jyoti speaks English to him and I speak Nepali. He speaks English, understands Nepali, and is set to outpace my Welsh in due course through a Welsh-medium education. The conversation continues.

So do I feel British? Will I ever feel Welsh? Such is the power of one’s formative wonder years, I will probably always feel fundamentally Nepali, no matter that I am more at home in the English language than in Nepali. But what of Kian? Like Jyoti, he will probably feel Welsh and British, and y Gymraeg will play a foundational role in this identity. If he spends any length of time in Nepal, like his mother, he may come to feel Nepali, too, not least because his command of the language will aid and abet this development. So I don’t worry too much that he doesn’t actually speak Nepali back to me – all I can do is lead him to the water.

But there’s a curious footnote here. For the sake of our narrative, I made the positive claim that both Dipti and Jyoti speak Nepali ‘to a reasonable degree’. This conceals a warp in the development of the ‘home language’ as envisioned by their parents. When I first met her sister and mother, I was bemused to discover that while Junu spoke perfectly standard southern Nepali to her daughters, they responded in what I can only describe as a pidgin Nepali, which to my ears sounded like a mishmash of Nepali and made-up words. Jyoti explained that this is a modified and simplified Nepali with Welsh syntax that the siblings invented and deployed exclusively with each other and their mother. As far as I can tell, it is a practical, elison-heavy pidgin, useful for relaying domestic information about comings and goings and doings.

With spouses and children in the picture, this is used less and less, although Jyoti complains about one-on-one conversations to this day – ‘I just can’t speak to my mother in English’ – as if there is some sort of cultural forcefield in play. This also appears to restrict the kinds of things they can talk about, as pidgin Nepali is, after all, a pidgin restricted to three. Oddly, Junu never corrected her kids, satisfied perhaps that she was talking to them in Nepali, that they understood, and that they communicated with her perfectly well.

All this makes me wonder whether, in equipping my son for a culture he may never live in, I am limiting the development of our own relationship, here and now. I speak to Kian in Nepali; he replies in English. He should have no difficulty expressing himself to me, but how does that work for me, as a Nepali writer who works better in English? Am I stunting our relationship from the get-go by taking on the approved mantle of cultural guardian? So long as we are grounded in doings and wantings and simple feelings, my Nepali will be perfectly adequate, and much more so than my wife’s pidgin Nepali could have been. But what of the future? In leading my son to the shallows of my explorations in Nepali waters, am I neglecting the deeps of the English I have taken on as my own? Will there be a confluence where these sources blend with each other, and can we navigate them together?

Watch ‘Meet The World: This is my ******* country!’ moderated by Rabi Thapa →

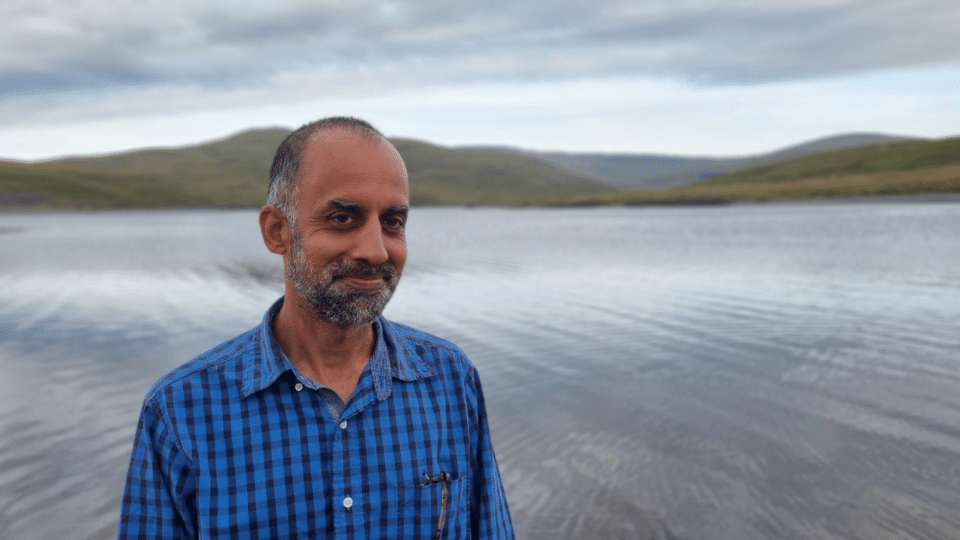

Rabi Thapa is a writer, editor and translator from Nepal, now working out of a village in mid-Wales. He is the founder Editor of La.Lit (www.lalitmag.com), and the author of Thamel, Dark Star of Kathmandu (Speaking Tiger Books). For Visible Communities, Rabi is proposing to “translate” the lived experience of Nepali-origin families in Wales through oral histories, with a focus on how they navigate language(s) across work and art. Rabi also undertook a Visible Communities residency at Dragon Hall in June 2021, during which he worked on a translation of Boni (1991) by the pioneering feminist writer Parijat (1937-1993).

Rabi Thapa is a writer, editor and translator from Nepal, now working out of a village in mid-Wales. He is the founder Editor of La.Lit (www.lalitmag.com), and the author of Thamel, Dark Star of Kathmandu (Speaking Tiger Books). For Visible Communities, Rabi is proposing to “translate” the lived experience of Nepali-origin families in Wales through oral histories, with a focus on how they navigate language(s) across work and art. Rabi also undertook a Visible Communities residency at Dragon Hall in June 2021, during which he worked on a translation of Boni (1991) by the pioneering feminist writer Parijat (1937-1993).

You may also like...

‘Sharing Stories, Connecting Lives’ digital zine

Discover this bilingual zine, created by writers and translators in collaboration with PEN Myanmar, on our cross-cultural online short story course.

23rd January 2024

Watch ‘This is my ******* country! Bad language and good living in the UK’

Watch this Meet the World panel discussion, exploring the experiences of Nepali Gurkhas living in the UK through the lens of language, cultural expression and identity.

9th November 2023

PODCAST: In Conversation with Rabi Thapa

On the Katmaundu literary scene, bridge languages and the 123 languages used in Nepal.

25th April 2023