How has language affected how Nepali Gurkha-origin individuals and communities integrate, dissociate or simply live life in the UK? How does this vary across generations and genders? How is this intertwined with cultural or artistic expression? This Meet the World panel explores the experiences of Nepali Gurkhas living in the UK to understand how the use of language – or the inability to use a specific language – defines their identities in the fraught multicultural realities of Britain today.

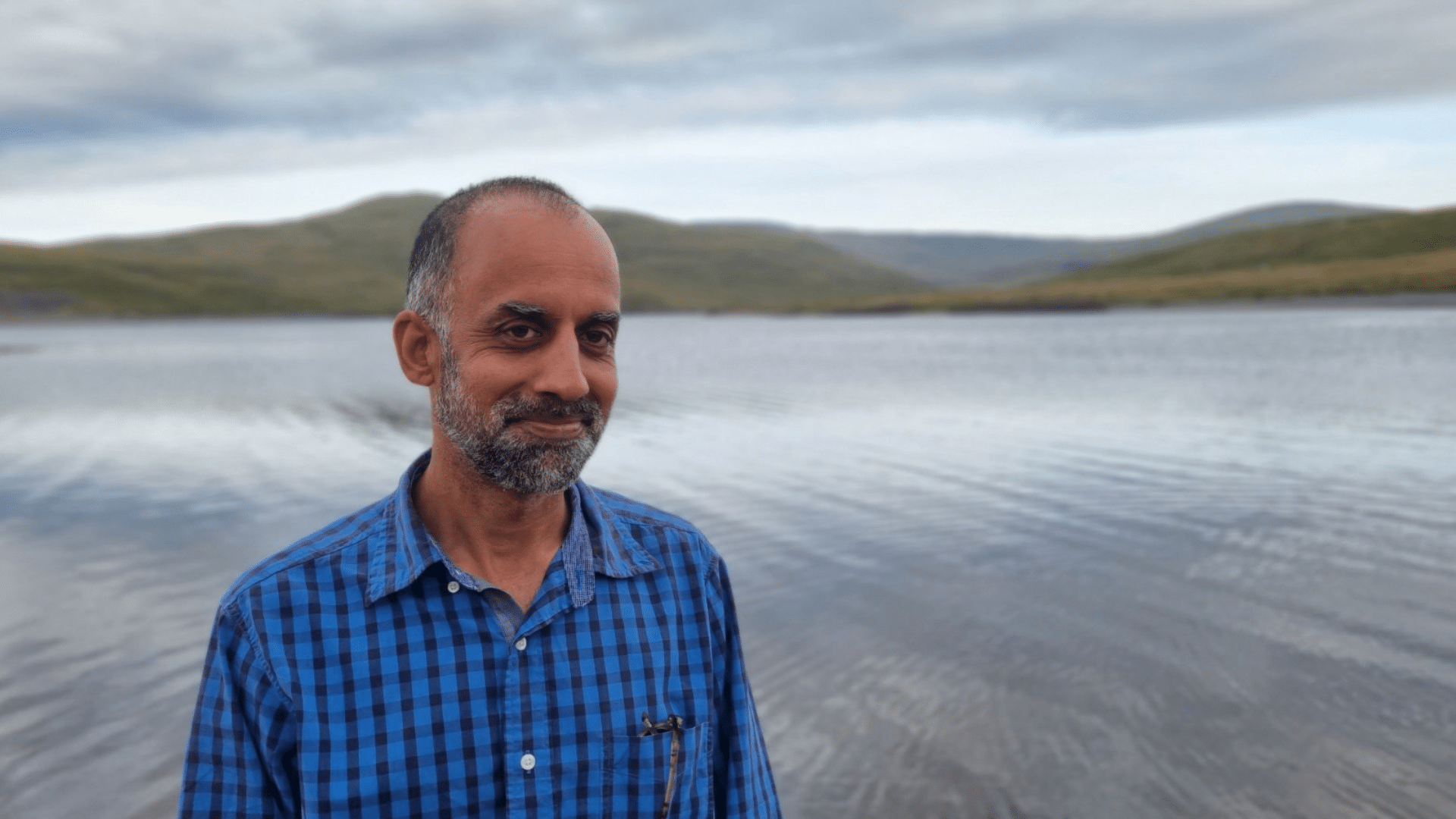

The panellists for this Meet the World session are Premila van Ommen, a researcher on Gurkha youth culture in the UK; Mukahang Limbu, whose debut poetry collection ‘Mother of Flip-Flops’ was published by Out-spoken Press in 2022; and Sanjay Sharma, a researcher on the transnational histories of Gurkha women. The session was moderated by Rabi Thapa, NCW virtual translator in residence for summer 2023, a UK-born, Nepal-bred writer/editor/translator who lives in Wales, hoping one day to be one of the Cymru Cymraeg.

Rabi’s residency forms part of our Visible Communities programme, which offers a range of professional development opportunities to UK-based Black, Asian and Ethnically Diverse literary translators, and literary translators working from heritage, diaspora and community languages.

Discover the recording and transcript below.

This is my ******* country! Bad language and good living in the UK transcript

With Mukahang Limbu, Premila van Ommen, Sanjay Sharma and Rabi Thapa

RABI: I’d like to welcome everybody to This is my bleep bleep country! Bad language and good living in the UK and I’d like to wish everybody a Happy Dashain because today is a big day, not just because we’re doing this panel but because Nepalese across the world are marking the celebration of the victory of good over evil by traipsing over to their relatives, getting their blessings and making merry. And because I happen to be in Wales in the UK, I’m not quite part of that but I’m happy to be here celebrating language. Thanks to the National Centre for Writing for hosting this panel under the Visible Communities programme and today we’re going to be talking about language and how language has affected how Nepali-origin individuals and communities live life in the UK. So, how does this vary across generations, across genders, how is this mixed up with cultural or artistic expression and, specifically, this Meet the World panel is exploring the experiences of Nepali Gurkhas living in the UK to understand how using a language or being unable to use a language affects their lives in this difficult multicultural reality of Britain today.

So I’d like to welcome and introduce our panellists for today. We have Sanjay Sharman, who has recently completed a PhD in Sociology from the National University of Singapore and his thesis was titled Patriarchy on the Move, Transnational Experiences of Gurkha Women and he also runs the Instagram and Facebook pages Gurkha Women. We also have with us Premila van Ommen, a researcher on Gurkha youth experiences in the UK, as well as an activist for Gurkha rights, and we have Mukahang Limbu as well, who’s a poet whose debut poetry collection, Mother of Flip-flops, was published by Out-Spoken Press last year and he’s a three-time Foyle Young Poet. I’d like to welcome all three of you here, great to have you, and I look forward to our chat today. Premila will be talking about the role of rap and hip-hop in the youth culture of British Nepali youth, Mukahang will be talking about how he and Nepali youth are using poetry and prose to express their lives in the UK, and Sanjay will be telling us a little bit more about how he’s used oral history methodologies to record the often hidden lives of Gurkha housewives and Gurkha women in general. So before we actually start, welcome to the audience as well. There is an opportunity throughout to ask questions. If you have any questions for our panellists, please type them into the Q&A box and we will address them as we go along and at the end, depending on how many we get. So please feel free to type in your questions and we will deal with them in due course.

Before we go to the panellists, I’ll take this opportunity to give you a bit of context on the Nepali diaspora, particularly the Nepali Gurkha diaspora in the UK. Some of you may not know that less than 1% of Nepalese in the UK were here before 1981. The 2001 UK census recorded only about 6,000 Nepali-born people in the UK but ten years later this had already shot up to about 50,000 and today the Nepali Embassy in the UK claims that there are about 150,000 Nepalese living in the UK, which probably includes Nepal-born as well as UK-born Nepali-origin individuals. So that’s a huge rise in the Nepali diaspora and about two-thirds of this diaspora is made up of Gurkha soldiers – veterans and their families – and they’re based mostly in the southeast of England and army bases scattered all across the UK, including Wales, where I am. There are obviously some key factors behind this massive rise in the Nepali diaspora in the UK, particularly the Nepali Gurkha diaspora, and it relates basically to the UK government. Until 2004, Gurkhas who had served in the British army were not allowed to settle in the United Kingdom. Thereafter they were allowed to settle in the United Kingdom with their families if they had served in the British Army after 1997, which is when the Gurkha Brigade headquarters moved from Hong Kong to the UK, and after a huge campaign in the UK, a highly publicised campaign, Gurkha soldiers and their families who had served before 1997 were also allowed to settle in the UK. So basically, most Nepalese who came to the UK have settled here between 2004 and 2011. Premila and Sanjay, you can correct me if I’ve gotten things wrong. So we have a huge Nepali diaspora in the UK and they’re very active. By an approximate count there’s probably about 500 Nepali-based organisations in the UK at the current time and some of them are religious, some of them are ethnic, some of them are based on the region in Nepal these Nepali have come from, and some of them are professional. We’re not actually going to be going over what these organisations do in the UK because that would take more than one session, but we’re going to look into how various subcultures and sub- communities within the Nepali diaspora in the UK get by in the UK, how they live life, how they express themselves and, in particular, we’re going to be looking at language and the role of language. How important is Nepali as a language to being Nepali in Britain, to being British Nepali? How important are the other languages that certain ethnic groups that make up the Gurkha recruitment speak, such as Gurung, Tamang, Limbu, Magar, Awadhi? How important is English to their lives? Not everybody, particularly the Gurkha housewives, speaks English to the same level as the rest of their family. Indeed, in Wales we have Gurkha children who are learning Welsh at the moment. So how do their lives translate through language? What do they lose of their home cultures and what do they gain from the host culture in the UK?

We’re going to be ranging across quite a broad set of groups and our panellists will help us navigate this sometimes contentious terrain. I’m going to start with Sanjay. Welcome, Sanjay. Just to begin with the basics of how language can help or hinder survival in a new place, we’re going to start with the real basics and then we’re going to go on to artistic and cultural expression. We know that Gurkha men who served in the British army would have picked up English to varying degrees, depending on when they served, where they were posted and where they retired, but as a broad generalisation it may be safe to assume that what served them in the Army would have been sufficient for life in the UK and many of them would have retired after fifteen years or so when they were still relatively young or just in middle age, so their command of the English language may have been sufficient for them to embark on a second career in the UK. But what about their wives? Obviously there’s a difference between the Nepali Gurkha women who served as midwives, who served in the Army increasingly, but maybe you can give us a bit of an overview of who this group is that you cover in your Instagram and Facebook pages, the hidden Gurkha women, and how they have survived or faced challenges as regards language. So over to you, Sanjay.

SANJAY: First of all, thank you for having me. All the information that I share today is based primarily on women in their sixties, seventies and eighties. I talked to a lot of those women during the lockdown. So when we talk about Gurkha women, it’s a general understanding that it is mostly the wives of the Gurkha soldiers, which is largely true. But there are also women who were part of the British Army itself. For instance, the QAs, who were nurses. Radha Rawat was a major in the British Army. She was actually a nurse and served in various countries with the Gurkhas. So what I’m trying to say is that while there is a big chunk of the population that is Gurkha wives, there is also another group of the population that is often ignored and overshadowed, which is the population of the professionals. But let me begin with an anecdote about the role of language when it comes to Gurkhas, especially Gurkha wives. In 1971, a woman from Nepal went to Hong Kong. It was her first overseas trip and she was living in the Hong Kong barracks and her husband was out for his day duty and an inspection visit came in. The inspection visit was accompanied by a Gurkha major and a few white British soldiers. The Gurkha major noticed that the woman, Indra Gurung, had kept chickens in her quarters and the major said, ‘You cannot have chickens in your quarters,’ and the woman said in Gurung, ‘Okay.’ But then when her husband came back later he said, ‘Why did you speak in Gurung? You should never speak in Gurung in the barracks. You should speak in Nepali.’ That is how language was policed in the yesteryears. It is being policed nowadays as well. For instance, the focus on English, primarily because most of the Gurkhas are in the UK and English is their primary language and they have to learn English to sustain their lives in the UK. But we have had rough histories learning one particular language because they belonged to a particular language group and were forced to learn a different language in the yesteryears and it continues in a different state now. So when I see this – I’m talking about the old generation of women, there are younger women who are able to switch between English and Nepali or English and other languages with ease – but this group of older women, who were primarily uneducated and had no formal education, struggled a lot when it came to their lives in the UK. So what does the Gurkha women’s history look like? It was in the mid-1950s that the first group of Nepali women came to the UK. As I mentioned earlier, it was Radha Rawat and Bimala Dewan who started their journey from Nepal via Malaysia and Singapore to the UK. They went there as nurses and a lot of other nurses followed. Then, in the early 1960s, there were women who came with their husbands, who worked in Buckingham Palace as guards, and the women lived in the vicinity of the palace. Then, in 1962, there were 1,700 workers stationed in the UK. However, there were only quarters for ninety-six families out of the 1,700 workers. Those ninety-six families and the others lived mainly in Lyneham in Wiltshire, where the Army base was then. And then, as Rabi already mentioned, after the Second World War a lot of Gurkhas went to the UK after winning their residency and citizenship rights. I think that is what I have to share about the movement and the language-related history.

RABI: Thanks Sanjay, that’s great. It gives us an overview of older generations, older women, and the difficulties they may have faced and probably continue to face in the UK. So just to leapfrog over to the younger generation, I’d like to go to Premila. I’d like to ask you about how younger people, the kids of these women or in some cases even the grandkids with Nepali and or Gurkha affiliations, through the medium of hip-hop, how have they managed to express themselves in their day-to-day lives in the UK? Through a talent in using language, say if you’re a rap artist, how is language setting them free and what languages are we talking about exactly? Can you give us a sense of this subculture as practiced by young Gurkhas in the UK today?

PREMILA: Yes. In terms of the different languages that the youth are navigating, you could call them different dialects of English. Most of the youth are based around the south of the UK, so it’s very much a Southeast English accent. You don’t really hear much rap in Scottish or Northern accents. Not just with the Nepalese youth in the UK but basically all spectrums of different migrant youth and British youth in general, the music that they tend to follow that becomes popular is British urban music and so they use the language which is often a mixture of what they call Roadman dialect. Roadman dialect co-ops a lot of Jamaican Patois and then they mix that with South London slang and together that forms this Roadman dialect and that’s the most prevalent language that the youth are using in their music. There are some youth who are much better in just rapping in pure Nepali and then there are those who will mix Nepali and English together. Often it’s a mixture and what I’ve noticed with the youth, in terms of their language proficiency, is that it depends on what age they came to the UK. That shows how good their grasp of English or Nepali is and those who are younger find it more difficult to be very proficient in Nepali.

RABI: Great, thanks Premila. I think with these, as with many other things, it’s very difficult to get a sense of what exactly you mean when you talk about a mix of languages. It’s probably a good idea for us to play this very interesting clip that you’ve made up for us. So let’s have a look.

[Clip]

Thanks so much, Premila, for putting that together. It’s beyond entertaining. It sent me down several rabbit holes of so-called research. I’ve been playing these Gorkhali Grind things and my wife would come in and I’d say, ‘Yeah, I’m working, this is part of my work.’ It’s really quite incredible, the range you can find and you can just look this up and go through YouTube and come across all sorts of things. You can’t really make out what’s from Nepal and what’s from the UK. In this clip there’s some songs which are very obviously speaking about the racism faced by Nepalis, those of Gorkhali origin being equated with Southeast Asians and subjected to that genre of racism. There’s clips in there where they’re talking about their elders, maybe not something that you get in mainstream hip-hop. There’s even references to children’s alphabet rhymes, and of course there’s lots of reference to the so-called Gurkha bravery, which we might talk about later if we have time. One clip that wasn’t included that was part of my research has this rapper called Goli, who I believe is based in the UK, and he says,

[speaks Nepali]

Essentially he’s saying, I love all languages and cultures but they don’t understand my lingo, they’re laughing at me, so my heart is Nepali but I’m a foreigner in a foreign land and I’m a foreigner in my own land, by which he means Nepal. So there’s a very keen sense of resentment and regret going on there, which I find very interesting because this particular rapper, to my mind he speaks Nepali fine, just perfectly, but he still feels like he’s a foreigner when he goes to Nepal. And then, you might watch a clip and not really make out that it has anything to do with Nepal and suddenly there would be a reference to Wai Wai in the middle of a song, something that most Nepalis can relate to – this particular brand of instant noodles which is kind of ubiquitous in Nepali diasporas across the world. So yeah, it’s really interesting and I’d like to move over to Mukahang now, thanks for being patient. What Premila was talking about and what we saw in the clip, how do you relate this to your own experience of writing poetry in English and the use of language to express yourself or mixing up languages? How do you relate to this in general?

MUKAHANG: I think one thing that really stood out to me is the use of slang, especially the amalgamation, because I grew up with that road talk. I grew up in that Southeast kind of community where the Nepali youth were using that kind of slang. I didn’t feel comfortable using that kind of slang because I was meant to be a good boy. I was reading books and it felt like an appropriation of language but I felt it was like a way for them to fit in. My way of fitting in was excelling in academics versus other people who want to fit in with what the common speak is, whatever the lingua franca is. But I think what that translates into is really interesting, especially in the genre of music. That’s not just grind but it’s also Afrobeats, and there are various genres being mixed through English as this middle-ground language, which is very interesting. For my generation, coming here when we were six years old, we pick up the language much more quickly and Nepali becomes a bit more strange for us. There are more gaps and more distance between us and so I think English becomes this anchoring basic language which we then use to understand our Nepali experience, which is in itself so ironic, using English to understand our Nepali way. That’s what I feel is being done in my poetry. And there’s also a difference between what people might consider high art language, so to speak, academic English or academic language, which exists also in Nepali, because I don’t have access to academic Nepali whereas in English I have access to academic English, whereas other groups, other youth might not have the same level of access to English academic speak and so I think there is this interesting juxtaposition between the two. There’s always that fiction, which is a difficulty, especially for young writers and young creatives.

RABI: Thanks for that, Mukahang. We should have an opportunity to hear some of your poetry a little bit later on. I want to switch back to Sanjay. But before I do that I’d like to remind our audience that you can ask questions. Just type them into the Q&A box and we’ll get to them. So please do ask questions. Sanjay, as we said earlier, we know there’s a sense that certain kinds of Gurkha women were kind of hidden, being restricted to the domestic sphere, unlike their men, mostly due to their limited knowledge of English. Do you have examples of these so-called hidden women being able to express themselves artistically and culturally in the UK? Apart from the obvious community-based events where you have Nepali dance, Nepali singing. Do you know of women who have written in English or Nepali in the UK? I think there was a particular example, Memoirs of a Gurkha Wife During Lockdown, which we did an interview on some time ago. Are there examples like this? Maybe you can tell us a little bit about that. Are there women working in other languages, such as Gurung, Limbu or Magari for example?

SANJAY: That’s an interesting question but sadly the literary community is very backward. One of the key reasons is because most of the women I talk to, as I mentioned earlier, didn’t have any formal education. They’re not able to write the way you and I are talking about. But Memoirs of a Gurkha Wife During Lockdown is a key example of how women are expressing themselves, in this case in the English language. Lila Seling Mabo is the author of the memoir and she talks about her own everyday life during lockdown but she goes back in retrospect to when her husband was away fighting in Iraq. So she draws parallels between her life during lockdown and when her husband was in Iraq, the kind of uncertainty that she had during those times. She has also been writing in the Nepali language. There are other people who write in the Nepali language because English is probably the second or third language to them, so writing in Nepali is easier. But if you talk about the younger generation, they are more expressive in what’s written and other artistic forms. But one of the key things that happened recently is the Gurkha women being able to express themselves through social media, for example TikTok, where they do not just showcase their cultural side but also show their artistic side, mixed in with their tradition. The kind of dances they do and the kinds of attire they wear are a marker of the heritage that they carry, the experiences they have brought throughout their travels from Nepal to Hong Kong, Singapore and now finally to the UK. All these experiences that these older women have are expressed. I don’t know if the identifier for artistic would be applicable here, but if you look at the TikToks that these women made, they are profound, they have a lot of research material in there.

RABI: Thanks Sanjay. You make a good point there. I mean, what is artistic? We don’t want to place an arbitrary kind of line between what constitutes art and what’s high art or low art, that sort of thing. But in terms of these older women, obviously there’s these ongoing issues and concerns on the part of the older generation that the younger generation is not able to speak various languages to the same extent. Their kids may be speaking English much better than they did but maybe they’re not speaking Nepali, certainly they may not be speaking Gurung or other ethnic languages. Is there a very obvious sense in which these Gurkha women could contribute towards the younger generation holding on to Nepali languages and keeping them connected with their heritage?

SANJAY: It’s a very good question. Probably a criticism I have of myself and the youths I work with and my friends is that when we work with the older generation of Gurkha women in the UK we generally tend to see them only as receivers. So when we work with them we generally tend to teach them English or teach them the way of life in the UK. We have never thought of working with these women in a mutual exchange manner where we can learn a lot of things from them. For instance, language and the kind of culture that they have been exposed to. We can be critical of the culture as well, but it is important to learn the culture they have been born and raised in and the kinds of histories they have. So whenever I talk to people, generally they are trying to intervene in these women’s lives like these women are only receivers. So I think that using a feminist approach, which I generally do, trying to break the hierarchy, trying to dismantle the power relationship that exists between people who know certain languages, would help a lot in the sense that if we tell the older women that there is something they can give us and we can also give them something in return, then I think the relationship is more powerful. One of things that I’ve noticed is that, as Mukahang and Premila said earlier, the younger generation of Gurkhas are moving towards English and there’s a disconnect between the older generation of Gurkha men and women, who have limited English knowledge, while the younger generation have limited Nepali language. So the disconnect is growing and I think through writings, through literature, even through Tik Tok and social media we can bridge the gap that has been increasing recently.

RABI: Thanks Sanjay. None of us would probably think of our mothers as just receivers because they give us so much. So, Mukahang, reading through your collection, Mother of Flip-flops, it’s so clear to me that you’re not just reaching out to your Nepali heritage, but you’re also reaching out to your mother in so many ways and to your childhood. Maybe you could read one of your poems. Would this be a good time?

MUKAHANG: I can read this poem I wrote when I was in Singapore working on a similar project to what Sanjay is doing, transcribing Gurkha wives’ experiences but through creative means and essays, and this is just a poem about some workers I noticed at a food stall. It’s called Makansutra Gluttons Bay.

Makansutra Gluttons Bay

two Gurkhas are led food stall to food stall

in this fish-sauce heat — smart shirts tucked tight

like a closed mouth. their nepali way of walking

tastes different to the nutty satay on my tongue,

it’s unlike my tart pink drink, but rather tastes

of Dettol soap, sweat & a little bit of pre-cum.

my almost retired sniper uncle points them

out as ‘fresh’ because we see the jhilimilī flash

across their eyes, how their brown faces sweaty

soak in this foreign humidity and their newly

enlisted bodies are awake like cicadas in the bushes —

‘at first you keep looking looking because everything is so glittering glittering’.

i think i saw the skinnier one on Grindr, though

it could have been another trooper with a buzz

cut, another thick-bushed profile with the bio:

a man who is not scared to try anything under the sun

that does not kill me. how often does he let another

man bring him to a little death until a Gurkha becomes

afraid of dying? i don’t want to turn these soldiers

into metaphors for bravery, manhood, migration,

or symbols of hardship so hard it makes your nails

go black. are they fools or heroes running 2.4km

under 9min 45sec? I’m trying hard now not to

imagine these two, beer-bellied after twenty years

of service still smiling like the village idiot, eating sting ray

for breakfast, guarding the Kim Jong Uns, containing terror at

home as eastern fathers might, well-meaning

semi non-verbal fathers. it’s best to deny

them such posey poesy, unwrite their not yet thick-hipped

wives, their fat happy broken-nepali children,

and simply leave them to this heat, with the food in their hands

they don’t know the names of.

RABI: Thanks for that. Great. Interesting mix of bits and pieces of Nepali scattered in there, which I enjoyed. The ‘jhilimili flash’ is nice. In your chapbook, Mother of Flip-flops, there’s a particular poem which talks about your inheritance and there’s a line that goes ‘Nepalese writing you can no longer read.’ So, without wanting to guilt-trip you, is there a kind of regret here or a guilt that you’re separated from your cultural inheritance by being here in the UK or do you just feel comfortable leaning into it and drawing that out into your poetry?

MUKAHANG: What’s really interesting about that question is the fact that what you picked up on was this feeling of guilt and regret and, looking back, I do feel that level of regret of not being able to sustain my Nepali. I was thinking of the last time I was conscious of being able to read Nepali, which is when I came home and my father had written a little note in Nepali on the table when I was seven or eight and that was the last time I was able to use that skill and now it’s been forgotten. But one of the things is I never really felt guilty about forgetting Nepali, nobody ever made me feel guilty, and guilt, perennial guilt, is like a manifestation from some external body. Somebody has to say, ‘You should feel guilty about this’ for you think, ‘Oh, should I feel guilty about this?’ And I think that’s where the tension is. I was never made to feel guilty by my Nepalese family. None of them said, ‘Oh, you can’t read or write Nepalese.’ They didn’t make a huge issue out of it. However, my teachers, who were white, were like, ‘How could you let that part of yourself go?’ which was such a dichotomy in that sense because I think for us, especially for our generation, our parents do the work of getting us there and they want us to assimilate as best as possible for survival, to achieve the things that they aren’t able to. And so in that aspect, I guess not every family is like this, but they do neglect that preservation of Nepali culture or maybe just language versus saying, ‘It’s okay to learn English, it’s okay for English to be the main linguistic tool for you.’ So that’s where that poem also comes from. I’m leaning into that fact. It’s just a fact now that I can’t read Nepali.

RABI: Sanjay, did you want to say something?

SANJAY: Yeah, it’s interesting how Mukahang is talking about his teachers saying how can he forget about his Nepali heritage, especially the language, and then the Limbu language that is not even talked about in these spaces. I just wanted to add that.

RABI: I think those of us who have lived abroad, lived outside of Nepal, Nepali-origin people, have certain bouts of guilt about how we are away from home and in that sense away from our cultures, away from our families, away from our languages because things never stay the same, you’re always negotiating your own position between cultures. We have a comment here which says, ‘Your experiences seem similar to other migrant groups in the UK where younger generations understand English better than older generations and older generations understand their languages better.’ And this participant has also expressed surprise that Farnborough is mentioned in a modern urban rap song, but there you go. I also wanted to ask briefly, Mukahang, whether you feel, as a poet, that the experience of creating poetry is similar to that of other diaspora youth. It’s not unique to Nepali-origin individuals in the UK, obviously. Do you have anything to add on that?

MUKAHANG: I think there aren’t many Nepalese poets in the UK and that’s partly to do with our level of education when we are brought to the UK. So I guess for my generation, I was very lucky that I was able to do well in school and keep that going, whereas I think people who come here a bit older, when they come here in their late teens, that becomes a transitional period which is really difficult for them because they’re stuck in this state where they aren’t able to absorb the new culture so easily and quickly when they’re still hanging on to their cultures from back in Nepal and so they aren’t able to reach their full potential. So I think a lot of the up-and-coming Nepali diaspora poetry community is actually based more in Nepal. I know Word Warriors, which, Sanjay, you worked with. We don’t actually have a specific Nepalese collective, whereas there are South Asian diaspora poetry communities. Like Zindabad magazine, which is a zine that was created for South Asian poets. So I think there isn’t a focalised Nepali. Even within Nepali you have, as you said, Sanjay, Limbu and Gurung, but we’re so diluted in the sense that we belong in the South Asian diaspora community and although our experiences are different, and of course there are always going to be similarities between different groups and how you experience things, I think ours is unique in a sense because of our Gurkha heritage, because of the history. Especially in my mother’s generation, illiteracy is not talked about. There’s so much shame behind the generation before us in terms of being illiterate. You go to a certain shop and you might not be able to order the food you want and there’s such guilt and shame and embarrassment about that and I think that is a generational thing. I just wanted to add, to all the people who are participating, an open call to create this poetry community. So if you do want to be part of this Nepali collective, please send your emails to Rabi or me and hopefully we can create this specific group in the UK, which will help us cultivate and bring our voices to the front and just have more conversations with one another.

RABI: Thanks Mukahang. We already seem to have a request to read your poetry at the Nepalese Community Centre in Aldershot, so let’s follow up on that later. Premila?

PREMILA: Just to put the focus on Mukahang again, I wanted to ask about your relationship with the Limbu language.

MUKAHANG: I was actually going to respond to Sanjay but I was like, I’m taking up so much time by rambling so much, but yeah, I think there are so many layers. So if Nepali is one generation away from me, then Limbu is two generations away from me. Not even my parents speak Limbu very well. They understand it but they don’t really speak it and my grandparents speak it and it’s not just something within Limbu. Groups don’t really pass that down too much either. My parents understand it but they’re not able to converse with it. Actually, a funny anecdote is that my grandparents always switch to Limbu when we’re in the room and they’re talking to me. They always switch to the Limbu language when they’re speaking about me and I’d be like, ‘I’m here, I’m standing right here. I know you’re talking about me by code, switching into a secret language.’ And so that’s why I feel like it’s even more further away from me. There is a sadness about not even having the capabilities right now to pick up that language, so I think there is such a difficulty about that. I don’t know if that answers your question.

RABI: Premila, there’s a few things I want to ask you, I don’t know if we’ll have time for it, but it kind of goes along with a question that we have coming in here. ‘How does the Nepali language and its speakers in the UK negotiate with the specific masculinity construct of the Gurkhas as a martial race, specifically when it comes to the voices and expressions vis-à-vis non-heteronormative gender and sexuality context.’ That’s a heavy question. I was wondering whether we’d have time to get into the whole bravery thing but here we are. So, just in relation to Gorkhali Grind, where this idea of bravery and adversity as demonstrated by Gurkha soldiers seems to fit with the real or imagined gangland lives of Gurkha youth in British towns. We saw a bit of that in some of the clips, though not all. This may be satisfactory to many young Gurkha males living in the UK but how about young Nepali-origin women, do they also engage in this fiction? I’m calling it a fiction, take that as you will, but do they also express themselves in other musical genres or other art forms?

PREMILA: It’s interesting. Masculinity is a very important question and a factor to think about, the sort of art expressions. As we pointed out, the idea of the martial race is something that people start internalising but that is also to do with young men and very heteronormative, so their music tends to be about bravery or fantasy and it kind of mixes well with the idea of gang culture and bravery as well, whereas with the women they don’t have that sort of music. There is one female rapper but she moved from Nepal to Essex and then to Belgium and now back to Nepal. Nepalese female rappers tend to try and take on this bravado but they don’t internalise the martial race. It’s more about female empowerment subjects, but usually the way that women express themselves musically will be often to do with love songs or parental problems or relationship issues rather than fantasies about being drug dealers or gangsters or just anything brave. Yhey tend to stay away from those subjects.

RABI: Thanks for that. It’s interesting because we have Panasha Limbu saying hello to us and she found out about the panels from Premila. She’s doing some research and some freelance writing about the new Gurkha warrior film, which I was actually thinking of mentioning because that’s one of the few things I’ve seen. I’m assuming she’s referring to the 2021 movie Gurkha: Beneath the Bravery, which seems to be totally buying into this idea that if a man says he’s not afraid of dying he’s either lying or he’s a Gurkha. Do we have any responses to that from any of the panellists? Sanjay?

SANJAY: One of the things that is often highlighted when I talk to people – I’m now talking about the Gurkha soldiers. When they talk about their past lives they tend to glorify how they, as soldiers, did this and that. But this should go underneath the nuances of the wars they were involved in. You’d both often end up crying when they explained about the people who died during the war, the friends who died during the war, the people they killed during the war, and when the bullets were being fired they were taken away by the moment but when they reflect about it now there’s a sense of guilt for killing and being killed. So the aspect of bravery is there, which they do not completely distort, but then there’s also the human aspect that is often neglected when the Gurkhas are talked about. Gurkhas are often portrayed as these heartless warriors but then their emotions are not talked about. The psychological trauma they went through during the war years, that is not talked about and I think there’s a niche that we as youngsters can write about, can research, probably portray through the arts, through movies, and then make the larger mass aware of what these men have gone through. And then there’s another layer of women, which I could talk about for the next hour. When the men were at war these women were separated and all the emotionality that they had to go through… but I’ll stop here.

RABI: Mukahang?

MUKAHANG: I just wanted to ask Premila about the notion of bravery and why is there bravery in things like gang violence and drug-dealing and those kinds of activities, when there are so many more complexities about being a soldier and being brave, but why is that so more resonant for the youth, do you think?

PREMILA: It’s an interesting idea, this idea of bravery. There’s this kind of wanting to make your parents proud, make your dad proud. There’s a kind of internalisation that I see generationally because it’s such a revered idea that Gurkhas have been brave for generations so therefore I also have to be brave. I’m not quite sure, it’s more a masculinity thing because often in subcultures, older subculture studies, when you look at things, especially in musical subcultures, often youth is about terms of rebellion. Even if you’re not a drug dealer but if you’re going to be rapping or pretending to be a drug dealer, it’s just a way to piss off your parents. But in the Gurkha context it’s a little bit different. It’s not so much about rebellion but more about ways to internalise bravery and also to connect with whatever is trending and cool around you.

RABI: That’s quite curious, isn’t it? We’re rapidly running out of time but I really wanted to touch quickly on this idea of Romanized Nepali that we spoke about earlier. Maybe you can give us a quick overview of what this means. I also wanted to add this idea that Gurkha soldiers were compelled to communicate with their superiors in Romanized Nepali, so how does this relate to younger Nepalis in the UK today who may not have the Nepali script? Would this be some way for them to be more Nepali by expressing themselves in Nepali?

PREMILA: Yeah, it’s an interesting question. Romanized Nepali is basically Nepali but written in the English alphabet or Roman script and there are two gaps. One is that Gurkha veterans back in the day were not taught Nepalese. They were recruited very young as teenagers, often underage, although they pretended to be eighteen and they didn’t really have that much education to begin with, often coming from rural areas, and when they were in the army they were told to write in Roman script. The elders themselves cannot read or write Nepali very well and that was their form of communication. Now, skip two generations ahead. Their children were able to go to school and their children’s children now in the UK, also not knowing Nepali scripts, they’re using Romanized Nepali. I wonder whether it’s going to be an interesting bridge of communication between the elderly pensioner generation, the grandparents, and the children. It’s also very important because in terms of services in Britain, whether it’s accessing the NHS or whatever, I’ve often had elders say, ‘I can’t read this Nepali translation but if it was written in Roman Nepali I’d be able to read it.’

RABI: That’s really interesting. I think we’re pretty much out of time now. We have a quick shout-out from a participant called Doug Walters who’s generally commending Gurkhas in the UK and I hope he’s enjoyed the panel as well, in all its complexity. I’d like to thank Premila, Sanjay and Mukahang for your contributions, it’s been really interesting. For the questions as well from our participants, I hope you enjoyed this session. I’d also like to thank the National Centre for Writing for hosting this panel under the Visible Communities programme. Special thank you to Kate Griffin and Martin Watters who helped set up this particular panel. So on that note, I wish you all a happy Dashain again and go and enjoy.

You may also like...

Watch ‘Meet the World: Translating Arab graphic novels’

In this Meet the World event, four writers and translators of recently published graphic novels from the Arab world discuss the translation process as well as identity, language and representation.

27th September 2023

Watch ‘Translators with Luv: Collaboration in Translation’

Watch this panel discussion between translators Anton Hur, Slin Jung and Clare Richards about collaborating in literary translation.

21st September 2023

‘In the Language Slipstream’ by Crispin Rodrigues

A commission from our 2022 virtual resident on code-switching, speech acts and biracial-bilingual identity

15th February 2023