What are the joys and what are the challenges of translating within the conventions of genre? How does translating commercial fiction differ from literary fiction, from translation to publication? In this event chaired by Dr Jacky Collins, translators Alex Fleming, Rosie Hedger and Megan Turney explore translating genre fiction – from Scandinavian noir to horror to speculative fiction and fantasy.

All three speakers are alumni of our Emerging Translators Mentoring Scheme.

This is event was co-programmed with BCLT as part of the BCLT Advanced Scandinavian Translation Workshop, supported by the Danish Arts Foundation, NORLA and the Swedish Arts Council.

![]()

![]()

Discover the recording and transcript below.

Translating Genre transcript

With Dr Jacky Collins, Alex Fleming, Rosie Hedger and Megan Turney

JACKY: Hello everyone. A warm, warm welcome to this translation studies webinar, Meet the World: Translating Genre. It’s part of the advanced Scandinavian Translation Workshop series run by the British Centre for Literary Translation. It’s wonderful to have you all with us for this session and before we begin quizzing the translators, I wonder if we can say that we’ll take questions throughout the session. So if you’d like to put your questions in the Q&A at the bottom of your screen, we’ll take those as we go. And I’d like to say, before we begin, a huge thank you to Kate Griffin and also to Martin Watters for steering us in this session. So without further ado, let me just say very briefly, I’m Dr Jacky Collins from Sterling University. I work in the Spanish and Latin-American Studies department but I began my academic journey many years ago at Newcastle University, where I did Scandinavian Studies, so it’s wonderful to be here for this session talking to translators who deal with those Scandinavian texts. Anyway, without further ado, let me introduce you to the translators. First of all, Alex Fleming. Hi Alex and welcome. Alex is a literary translator from Swedish and Russian into English, working across a range of genres, and her recent translations include

Anders de la Motte’s The Mountain King, Camilla Sten’s The Resting Place and Maxim Osipov’s Kilometer 101, co-translated with Boris Dralyuk and Nicholas Pasternak Slater, and Katherine Kielos-Marcal’s Mothers of Invention. She’s also editor of Swedish Book Review, a journal of new Swedish writing. Alex, I wonder if I could just start by asking you about the experience of co-translating. Could you talk to us about how that’s been for you?

ALEX: That particular project, Kilometer 101, and its predecessor, Rock, Paper, Scissors, are both collections of short stories that we worked on in groups of translators, from Russian, I should also say. So while we split up the stories in quite a straightforward way – we each took one and then looked over each other’s – it was actually a really rewarding way to work. You didn’t have those kinds of clashes in the actual translation itself but at the same time I took so much, especially working with translators that are more experienced than myself, from how they deal with the same sorts of problems and how you work together to capture that authorial voice in a similar way and make sure it’s consistent. So it was a wonderful experience and I really took a lot from it.

JACKY: Thank you for that. The translator’s journey can sometimes be a lonely experience and it’s great to work with others and have that chance to discuss things with others. Thanks Alex, I will be back to you. Next, Rosie Hedger, and I have to say a thank you to you, Rosie, because I’ve read some of the translation work that you’ve done. Born in Scotland, you completed your MA in Scandinavian Studies at the University of Edinburgh, where you graduated with a distinction in Norwegian. Rosie has translated works by authors including Marie Aubert, Helga Flatland and Agnes Ravatn and her translation of Gine Cornelia Pedersen’s Zero was shortlisted for the Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize in 2019. Her translation of Agnes Ravatn’s The Bird Tribunal won an English PEN Translates Award in 2016. And again, from me, a huge thank you for The Bird Tribunal. Rosie has lived in Norway, Sweden and Denmark but is now based in the UK. Rosie, I was going to ask you about the Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize because I’ve not heard about that. Could you tell us a little bit about that prize?

ROSIE: There were about ten of us who were longlisted and I think for me the best part of the event – I didn’t win the award – was that there were so many other translators there. Everybody who was longlisted came. They also had professional actors who read out excerpts of the text, so that was amazing, to see your text really come to life in front of the audience, and I think it was such a unique experience to see that and actually it didn’t feel like a competition. We were all just kind of sitting there and as translators we were like, ‘Oh, look at our work being read out!’ and saw how much life was being put into it. So when I think back to that award I immediately think of the event and all the people I met and it was just such a nice experience to come together and talk about things that we’ve been doing and things other people have been doing. I think that’s something that’s so communal. Events like this and a seminar we’ve been doing these past few days. We just like to talk about what we do because, as you pointed out, it can be lonely. I think part of it is that you are on your own and you are making a lot of decisions on your own. So to co-translate or to just get together with others is a huge part of it.

JACKY: Thank you, Rosie. Our third translator, Megan Turney, is a Stafford-based literary and commercial translator and editor, working from Norwegian and Danish into English. She was the recipient of the National Centre for Writing’s Emerging Translator Mentorship and holds an MA (Hons) in Scandinavian Studies and English Literature from the University of Edinburgh and an MA in Translation and Interpreting Studies from the University of Manchester. Megan, it’s wonderful to meet you, thank you for being part of this. I wonder if you could talk to us about that mentorship in 2019 that you received, the Emerging Translator. What did that do for you? How has that changed who you are as a professional?

ROSIE: I know Rosie and Alex are both alumni of the same programme, so we probably feel the same way, that it just completely opens doors for you as a professional. In literary translation, in particular, the industry just seems impenetrable, it seems so cryptic from the outside. You’ve just got no idea how you even get your first job and to me it just meant I got to hone my skills with an excellent tutor, Kari. And you get to meet all these people as well, so I don’t think I’d have gotten my first full-length novel translation had I not been in there because that’s how I met West Camel from Orenda Books and got my first novel and how I got the rest of my novels. So yeah, a huge difference and just great fun as well. All round, an excellent thing to take part in and I heartily recommend doing it, as I’m sure Alex and Rose do too.

JACKY: Wonderful that you were all part of that scheme, the NCW Emerging Translator mentoring scheme from the National Centre of Writing and the supportive network that has come out of it. Even in these first few minutes that we’ve begun to discuss your profession, the things that you’ve been involved in, these repeating ideas. Okay, so here we go. You have that Scandi link in common and I wonder where your desire to be translators came from? Were you drawn into Scandi Noir, which is where my passion lies, or were you drawn into translation from a different genre or style, either literary or commercial. Alex, where did it all begin for you?

ALEX: My interest came from reading a lot and I’ve always loved languages and I’m really lucky that I was brought up in a house where, although many languages are spoken, there was that constant interest in different cultures and different literatures. So I studied languages at university, not Swedish, but then life took me to Sweden and after university I was working there and obviously learning the language. I was working part-time so I had time on my hands and I was looking for other things to keep me busy. Swedish Noir or Scandi Noir were the books that I was reading as I was learning Swedish. They were the first books that actually became available to me in Swedish, partly because that was the boom and also because I think they gave a great insight into the culture and language, though, admittedly, they are very specialist and they may or may not be useful to you in your later life. So literary translation just sprung from a love of language and being able to play with words and language all the time.

JACKY: Thanks Alex. There’s a question from Helen that I’ve seen, but if we can hear from the translators first then I’ll come to your question. Megan, was it very clear when you were at university that you would be the translator that you’ve become?

MEGAN: It’s funny. Ironically, I was terrible at languages at school. I think if my French teacher were watching this and had seen what became of me, he’d be gobsmacked. I also really didn’t enjoy languages either but I think I felt a bit of an affinity for the Northern climes, so Scandinavian Studies was an option at university alongside English Lit, which I’d already set my heart on, and then it wasn’t until the end of second year, after we’d actually completed our first translation module taught by Ian, who I know is here, and it was the perfect mix of mechanical and a process and the creative because I could never imagine myself writing a book from scratch. But playing around with someone else’s words is perfect for me.

JACKY: I think what we can see is how the passion has certainly grown and developed. It might not be what you started to think about but then you had that experience at university that took you forward. So thank you. Apologies for any of the sound stuff there, no worries. We’ll keep moving, if that’s okay. Rosie, were you set on this from a tender age or did you also come to it in a roundabout way?

ROSIE: I think I have a very similar experience to Alex and Megan. Always a big reader, even started off at university doing English literature, took Norwegian as my third outside subject and just really enjoyed it. It was such a small group of people, a really small class, and that was just lovely, to come and feel like you knew everyone in your class when I compare it with when I learned French and there were three hundred of us in a lecture theatre. It’s just not the same experience and you can’t learn a language as well in those kinds of settings. So that kind of started it for me, doing a bit of translation, really finding enjoyment in that creative process. But, like Megan says, not having to come up with the entire plot yourself is very helpful. So, you know, just kind of following that path and being helped into that. I started translating before I did the mentorship scheme and Kari, who was my teacher as well, was very helpful in linking me up with people who were looking to have samples done, so I took it nice and slowly and worked in that direction. But I don’t think I would ever have imagined that. I didn’t come from a background where translator was on my radar, even though I think if someone had said to me you could do this, wow, that would be amazing.

JACKY: I think what comes out of the experience of the three of you is that sense of you never know when that moment might present itself and it’s not necessarily set in stone, that from the get-go this is what I’m going to be. Kate’s kindly put up the link to information about the NCW Emerging Translator mentoring scheme, so please, people that are with us, do avail yourself of that really useful information. Helen has asked a question, so I will throw it out to whoever would like to start this. She says, ‘I’m intrigued to find out more about the mentorship scheme but could you please point me in the right direction. I’m a newbie who’s emerging from teaching French and German and trying to establish a specialist area.’ So if we put that to the translators, how did you take those first steps of going into a specialist area and which area was that first specialist area that you went into? Rosie, do you want to set us off on that?

ROSIE: I think I did the opposite, actually, picking a specialist area, and how much picking was involved is another thing because when I started out I was doing short samples, so it was very much a case of being connected with someone, somebody giving my details and in this case it was Kari. She put me in touch with an agent, for instance, so it kind of went from there. But what I found helpful at the time was just to do as many different kinds of texts as possible. We’re speaking about genre today, but I did children’s literature, I did cookery books, I did a lot of commercial stuff, I did a catalogue about banisters that go down stairs, I did a diabetes survey, anything that was offered to me, pretty much, and by doing that I was able to find out what am I good at, not so good at, not so fond of, what am I willing to do for the money anyway, that kind of thing.

JACKY: Thank you. Megan, was it the same for you or did you go straight into that specialist area?

MEGAN: No. I’m laughing because that was word for word the exact same for me, for the commercial side as well. It’s a difficult industry in some ways and it’s just so fragmented, so getting the work is really about building a portfolio. So for me it was about honing my skills through all of the work that I was getting in, that I was desperate for, and then that meant I was guided as to where I felt my passions and interests lay and I think you’re very lucky if you can get straight into specialization but I certainly did try. I was certainly doing a lot of passion projects on texts that I really loved on the side, but of course not paid, so it’s difficult.

JACKY: I’d like us to come to that point as well of going from the training to actually being able to present a piece of work, that you know that that hard work is recognised by being published and being paid for that work. Alex, just to make sure that we hear from you about getting started and if you were able to work in a specialist area.

ALEX: I don’t have too much to add because my trajectory was exactly the same. I started off with commercial work, doing everything, knowing what I absolutely could not do, so no medical stuff or anything like that, but it took me time. I think Megan has touched upon how difficult it can be to get your foot in the door of literary translation but actually it was really good having that long period of honing my craft because then I knew what I could bring to the table.

JACKY: What strikes me from what the three of you have said is that willingness to serve that apprenticeship time and almost like watch and wait, but we will come back to that. Thanks again Helen for your question. I hope that’s helped and maybe in the sense of it’s not just going to come and happen, that time that’s needed. Just for an anecdote, I wonder if you could give us the funniest thing that, either as a passion project or as paid work, you have done. I like the banister text, but something that you never ever thought that your life would ever be involved in but you immersed yourself because that’s what’s needed and you came away with a bank of knowledge that feels like you’ll never be free from what you experienced. Alex, can you think of something?

ALEX: Actually, I am free of this knowledge but there was a while when I translated a pet shampoo website and so I knew all about the various allergens and things like that and I was quoting it for ages whenever anyone had a pet. But five years down the line it’s gone.

JACKY: It’ has washed away the allergy!

ALEX: Yeah, all these deaths and murders have it washed away.

JACKY: Megan, is there something that was part of your life for a while that was like, ‘What is this?’ and maybe you’ve managed to be free from it now?

MEGAN: It’s so funny because it’s constant in this job and I’m sure Alex and Rosie will say the same. For me one of the best parts of the job is deep-diving into a topic I’d never have looked into. In terms of funniest, I’m sure there are so many other funny ones I’ve got but I would say, with crime fiction, a lot of the time when you’re trying to really get something right and there’s someone describing how to load a gun or how to make a bomb and you’re doing this deep dive and you just know that you’re going to be on some sort of government watchlist and then your flatmate walks in and looks at your screen and you’re watching a video on how to load ammunition into a revolver. I’d say that’s probably mine.

ROSIE: Sorry, just to jump in. One of my authors was speaking about that very thing. She feels that after she’s been searching how to kill people with a dagger, she has to type into Google, ‘Don’t worry, I’m just an author, I’m just researching it.’

MEGAN: You just add ‘translation’ onto the end.

JACKY: It’s purely for research purposes, nothing sinister at all. Rosie, was there anything crazier than the banisters that you’ve been involved with?

ROSIE: I can’t remember much. I think the turnaround on commercial jobs is often so quick that it’s like it’s in one ear, out the other. I wasn’t thinking or getting involved but then when Megan talks about deep-diving for a literary translation it’s a very different story because you’re living with that novel or short story collection or whatever it is for months, it could be like six months, so you do have the opportunity to think and then think again and think again. I remember I was doing a really difficult project, a co-translation with Olivia Lasky, who might be watching this, and it was very old Norwegian, it was Danish basically. It was some travelogues by an author and they were so hard. We accepted the project and had no idea. We were just clueless and we were in different time zones at the time so we were writing to each other and I remember that I sent an email to Olivia. I was just like, ‘This project is awful, it’s pickling my brain, I don’t know what I’m doing’ and the author was copied into the email. Not the author, sorry, the person who commissioned the project and it was like you said, I just suddenly realised and I didn’t have the recall on to undo the email. I was like, ‘What have I done?’ I can’t remember but I think I just wrote an email like, ‘Oh, I’m sorry, I think you might have been copied into that email.’ Luckily, I think it was such colloquial English that she didn’t quite cotton on to it. But I just remember at the time thinking, that is easily the most embarrassing thing ever. I’m sure I’ve done more embarrassing things since then in translation but that one sticks with me.

JACKY: Yes, so be careful with those emails.

ROSIE: You know where you can undo it for thirty seconds? I turned that on immediately.

JACKY: Yes, very wise. Never mind translation skills, remember those technical skills. We have another question. Kathy, thank you so much for your question. ‘When we talk about genre, can you explain the difference between literary fiction, up-market fiction and commercial fiction?’ She says, ‘I feel like agents use these terms but it is a mystery to me.’ So, as translators, these three terms, when we say them, what do they mean to you? Are they distinct for you and how would you separate them? Alex, can you separate literary, up-market and commercial fiction?

ALEX: I understand why the categories exist and they serve an important purpose. But at the same time I think the barriers or the boundaries between them are impossible to set and they’re pretty arbitrary. Literary fiction borrows from genre or borrows genre tropes all the time and vice versa. Genre can be written in the most exquisite language and even genre breaks down into so many different types of categories or interests. I struggle to find a direct, exact definition that you can put your finger on to get a sense of the themes that are involved in different ones. Short answer. Maybe Megan or Rosie have a better one.

JACKY: Megan, Rosie, can you make the distinction and say what it is or are these boundaries not as fixed as we might think?

ROSIE: I think you hit the nail on the head there about it not being fixed and I think the one thing that makes me say that is that I have translated work which has been published and marketed as a very different genre from what it is marketed in its own country and what I would necessarily say that it is. In a sense, it’s not my fight to have, it’s not my battle to have, you know, ‘You’re getting this all wrong.’ So when I see the jacket, for instance, if I see that in advance, I can maybe say which one I think would be more suitable, based on my reading of the novel, my experience, but that’s a decision made by the, in this case, UK publisher and that’s on them and if they want to market a book a certain way then they can do that. They know things that I don’t know about sales, about all those aspects, so I would say that it’s not fixed and this idea of literary fiction is more a kind of gatekeeping term, I think, that it’s actually quite exclusive. Again, like Alex says, I know why these things exist but I think that you would struggle to find an agent who didn’t consider what they were pitching to you to be literary fiction. I think they would all say it’s literary fiction because that’s up here, we all want to be doing literary fiction, that’s the way they see the world. I work in a library and I’ve got to say people don’t come in looking for literary fiction, on the whole. They read a whole range of things and I think that being more open to the different types of genres that people are interested in and importing more of them from abroad might be something that would bring the numbers of translated books up.

JACKY: Thank you. Megan do you wish to add anything to what’s been said already?

MEGAN: I think that’s so accurate. I think it’s really a system level kind of thing. It’s a publishing industry market that translators don’t necessarily consider unless it’s in the marketing. I think an argument could be made that in literary and commercial fiction it’s all about the language that you use, but I think any translator that enjoys their job and knows what they’re doing is having fun with the language regardless of what kind of text you’re working on. We’re all trying to make the best text possible, so literary or commercial doesn’t really play a part for us. Having also worked in a library, of all the books I have scanned in, the absolute majority are crime fiction novels. People love them. And the way they talk to you about them, I think there’s no point in making them a hierarchy at all.

ROSIE: They’re so unfairly scorned, I think, or talked about in a withering manner.

MEGAN: Yeah, they’re popular for a reason. People love them, I’ve loved them. Similar to Alex, I started reading Scandi Noir when there was the big boom right before starting university and they were amazing. I think I bought a book a week because I was just so obsessed with them. I couldn’t wait for them to come out in the library so I just ordered them.

JACKY: Thank you, translators, thank you for that. There are a number of questions that have started to gather, which is wonderful, thank you for those questions, and just to respond to Lupa, if you could type out your question, because we’re not going to take live questions, if that’s okay, so just take your time typing out your question. I’m going to try and take these in the order they were put in the questions. So Rachel has the next question. Rachel, thank you so much. Rachel says, ‘Thanks for the discussion. I wonder do you ever worry about being typecast as a translator? That you will only ever be approached to translate crime novels because you’ve translated a number of them.’ So, getting pigeonholed because of the work that you’ve done. Does it bother you or do you not care because it’s a paid job? And that was my question on the end, not Rachel’s.

MEGAN: I don’t necessarily mind but I also think that while your name might be out there in the public and people are seeing what kind of books you’re reading or translating, behind the scenes you’re probably also doing a lot of samples for publishing houses and agencies and your name is getting about in other places just by virtue of doing these different samples. So I think even if you make a name for yourself on the outside doing certain texts, people don’t necessarily always consider that as the be-all and end-all because I think that a lot of what drives the publishing industry is money, so they see a good translated sample and hopefully then you’ll get through in different ways.

JACKY: Alex or Rosie, are you worried about being typecast?

ROSIE: I have seen trends in the kind of work I get but not from publishers, more in the samples that I do. Megan mentioned samples from Norwegian publishers or Norwegian agents. When I started out I got loads of children’s literature and then all of a sudden it stopped and then I had quite a lot of crime stuff come in. So I think in their mind you do something and it’s good and whenever they have that kind of thing they think of you and they send it to you. And that’s fine, that doesn’t bother me, although I did something that was a bit more experimental once, which is quite difficult, and now I keep getting sent quite difficult ones and I’m like, ‘Stop sending me the hard ones!’ So I think you can get typecast but I don’t think there’s any kind of logic behind it. I just think it’s literally like somebody thinks, ‘Oh, I’ve got a sample that needs doing, it’s similar to such and such’ and possibly that would happen with publishers but I think it depends if you’re working with the same publisher a lot or if you’re working with others and in my experience, when I have been working with various publishers, the books are similar, so I think it comes from whether it’s been commissioned through a sample.

JACKY: Thank you. I’m going to take the next question and Alex I’m going to start you off with this one. It’s Greta that’s put this question in. ‘Do you work on books that a particular publisher wants to have translated or do you find a book you want to translate and end up taking it to a publisher?’

ALEX: A bit of both but I would say that the majority of the books that I’ve done have been commissioned, initially at least, by an agent, a Swedish agent, and similar to what Megan and Rosie were saying in the previous question, I’ve done samples that may then have been picked up by a UK or US publishing house and then they’ve taken me on to do the rest of the translation. Especially earlier on in my career, I did a little bit of pitching and I still do occasionally try to give time to books that I really would love to work on that haven’t yet been translated into English but it’s just the demands of time and money. I stick mostly to commissions and I’ve been lucky to have had quite a variety of commissions so far. So that keeps the different sides of my brain or the literary muscles working.

JACKY: Thank you. Megan, have you ever gone to a publisher and said, ‘This is a great text, I’ll translate it. Will you publish it?’

MEGAN: I have so many texts lined up that I would love to pitch, some that I’ve done samples for and some that I’ve just read and can’t believe that they’ve not been published in English. But it’s similar to what Alex was saying. Time constraints and the fact that a lot of the time you are preparing this text for free, which is fine when you’re very passionate about it, but when you need to make a living out of it it’s quite difficult to find that time and pitching is just so difficult anyway. It’s very much about the network and it’s hard when you just don’t know how to contact the right people. So it’s pretty much always commissioning work for me as well.

JACKY: I think it’s an interesting point you raised, that idea of knowing the network, knowing who to approach, how do you get into that? And then even when you’re in, when there’s so much traffic, when do you get a chance to you say, ‘Excuse me, what about this one?’ Alongside the idea of ‘I have to take this next job because I have a mortgage or various things that need to be paid.’ Rosie, have you got a book that you found and were successful in pitching to a publisher?

ROSIE: No, I’ve never really properly had a go at that and I think it’s just the case that when I started out I was doing part-time translation alongside my other jobs. I was teaching for a number of years and doing translation on the side, and then I did a bit less teaching, a bit more translation, it kind of went back and forth, and nowadays I do part-time translation around family and around another job but basically, over the years, I’ve never really felt like I’ve got loads of time and I really want to pitch this passion project because you only have so many hours in the day, you have to do paid work and translation doesn’t pay particularly well. So for a lot of people that means having other jobs, which is nice. I actually think it really benefits translation to get out and do another type of job but I’ve never felt like it’s going to be healthy for me to sit in and do a load more translation on top of all the other jobs, which always tend to come in huge waves. It’s like buses, you wait and they all come at once and you’re churning through all of those and then they go and then it’s dead quiet but you just need a bit of a break and then it’s the same process again. So personally, for me, I work when I’m commissioned to do texts. I don’t think the success rate in pitching is that high. I don’t think it’s a good way to spend your time unless you have a very good contact and you have a very good chance of a particular text going somewhere. I just think it’s a really difficult way to do things.

JACKY: Thank you. The next question is from Ruth and she has been asking about a specific genre: graphic novels you have written with simpler language or less text. As people who are translating, do you feel they are growing in popularity? Megan, do you want to talk to us a little bit about that?

MEGAN: I’ve had an influx of them and they’re really fun to work on. I see the publishing house that sends me them posting a lot about their popularity in Norway and it’s incredible. I would love to translate one if there’s a publishing house watching. I don’t know about translated graphic novels in the UK but on the whole they’re really growing in popularity.

JACKY: Rosie, Alex, have you had any experience with graphic novels?

ALEX: I’m afraid I don’t, so I don’t have anything to add to this but I have seen more coming through.

ROSIE: I did a sample few years ago and then I extended the sample. It was published by Words Without Borders and it was so much fun to do. But the one challenge I hadn’t thought about in advance is not writing too much to fit in the bubbles. This was something that is so unique to graphic novels compared to a novel. You only have that space to work in and with Norwegian to English it does tend to be longer in English, just naturally, so that was a challenge that I hadn’t anticipated. That was a really interesting learning experience, just thinking, ‘How can I get everything in that I need to in a really short and snappy way?’

JACKY: You saying that makes me think about subtitling as well. You’ve got that box and you have to convey the message in the frame within the box. It might be fewer words to translate but then there’s that getting the message in. Charis has asked a question, this is lovely. A book recommendation from each of you. Presumably it can be one that you yourselves have translated but maybe a book that has yet to be translated, we could take that, or a book that you know that should definitely be in translation. Megan?

MEGAN: I recently read Cursed Bunny by Bora Chung. It’s short stories and I love short stories and it was incredible. I heartily recommend that. Translated by Anton Hur.

JACKY: Thank you. Love the sound of it, thank you. Alex you were going to ask a question.

ALEX: I have a couple of options but does it need to be in a particular genre or just any book?

JACKY: I think the question is a book recommendation, there’s no stipulation.

ALEX: One book that I’ve been reading recently is Ia Genberg’s The Details in Swedish that has recently come out in the States in a translation by Kira Josefsson and it’s a wonderful book about a life viewed through its fragments and portraits of people that were central in that person’s life. That’s a really lovely book. In suspense or crime, I really love Stina Jackson’s work and she’s been translated into English as well.

JACKY: Thank you. Rosie, recommendations?

ROSIE: It just came to me randomly there because I read it a few years ago, but Roy Jacobson’s The Unseen, translated by Don Bartlett and Dawn Shaw – I was just checking it was definitely who translated it – I thought that was really great. I read a lot and books kind of come and go but some linger and I think for that one the setting really lingered with me and the characters. There was a lot of clever stuff in the translation as well. So that would be my recommendation.

JACKY: Beautiful, thank you. Just to people putting your questions in, it’s really good, you’re saving me an awful lot of work here and it’s lovely because it’s good to know what you’re wanting to hear about. Kasia Beresford says, ‘I’m translating a thriller with a realistic setting. I spotted some inaccuracies relating to the setting and emailed the author with them. I got a friendly and useful reply but also a list of issues raised by a geeky fan that need to be reflected in the text. The author is asking me how would I like to approach this? So what would you recommend? Author rewrites in source language and retranslate? Work on it together in the English – author speaks decent English – via Zoom?’ So, dealing with these issues with the author, how would you advise to go about that?

ROSIE: I think it depends if there’s a publisher involved or not. I can’t tell from the question, I was just reading it there. If this is going to be published and there’s a publisher in the language you’re translating into, I would turn to them and ask them because I’ve seen a range of things done. For a translation that I did recently, the publisher felt the ending was not very clear. So I spoke to the author and the author said, ‘Yes, I want this opportunity to clear things up because I’ve had people coming to me in Norway and saying, “What happened at the end? I don’t understand.”’ So the author wrote something in English, which the editor then polished up. I didn’t play any part in that but there were other options as well, the kind that Kasia suggests. So yeah, ask the publisher, the editor, I think. That would be my first protocol.

JACKY: Megan, Alex, have you worked with an author like that where you’ve been on Zoom with them or you’ve discussed things in English with them? Alex, how have you done that?

ALEX: Yes, and actually for one of the more recent books that I’ve translated, which is coming out next year in English, some of the references were far too Swedish and the jokes just weren’t hitting home, so he actually wrote entirely new segments. We’re talking quite short segments, only a couple of paragraphs, but just so the chapters flowed in a nice way and you weren’t left wondering. The focus was on the story rather than just on an English language reader being puzzled by what’s going on. So he actually wrote sections in Swedish and I translated. But I think if a publisher is involved in the project then you need to be clear about what your responsibilities are. If it involves significant rewrites then that needs to be compensated for and you also need to be really clear what it brings to a text. Yes, corrections need to be made and those sort of editorial changes should be caught with the help of an editor. But it’s really good to have an open sort of communication with the editor and with the author as well and I’ve always found that very beneficial in my work.

JACKY: Megan, would you like to add anything?

MEGAN: I’ve been in a similar situation where I found inconsistencies in works that I’ve translated that have obviously been missed in the editorial stage in the source country and I found that when it comes to actually working with the authors, a lot of the time they have been far too busy to get on a Zoom call with the likes of me. So I’ve generally sent them emails back and forth discussing options and sending solutions because at least then I’m providing something that I think would actually work in English. I think one of the risks is that you could send something and get something back with the same kind of an issue because if it’s there in the source it might still be there, it might not be fully comprehensible for a non-English speaker. So I would say if you need to talk and work with the author, go with the options, go with the solutions.

JACKY: Thank you. Kasia said the publisher has been involved. Translators, thank you so much for the advice there, that’s been really helpful, thank you. The next question, if we scroll down, this is absolutely wonderful, these questions, I’m loving it. It’s from Charlotte. Charlotte says, challenge here for the three of you now, ‘Where do you see yourselves in two years with regard to translating? Editing literature that has been machine-translated or AI-written, or some other variant, and will genre be a factor?’ Some aspects that I wanted to ask you about as well, about the looming shadow of AI and what that means. So, Megan, where do you see yourself in two years’ time?

MEGAN: I would love to be working on more children’s and young adult fiction and speculative fiction because I know it exists in Norway. It would just be nice to work on more of it. And graphic novels, obviously. I’d love to still be working on those and having them published. I do not want to be post-editing machine translation in fiction. I think that’s more of an issue in fiction than it is in commercial translation, although I still think it’s an issue there as well for many reasons. I just think with fiction there is so much lying in each word choice and at the end of the day it just takes away entirely from the craft and from the joy of reading and having transferred something from one language into another without it just being word for word. I think doing that is kind of disrespectful to what it actually takes to translate something. So none of that in fiction, please.

JACKY: Okay, thank you. Rosie, for yourself, two years’ time?

ROSIE: The mention immediately of AI is interesting because it will impact what I do. Like Megan, I would be opposed to editing things that have been machine translated, not because I am particularly anti-AI but more because I’ve edited other people’s translations. For example, in a case where somebody did a translation and the publisher wasn’t happy, they gave it to someone else to improve and it was a nightmare, so much more difficult than just doing it yourself. So I think for me, if the industry moved in that direction, I would probably move away. But doing more of the same, I guess. In a sense, translation is a hard job because there isn’t a natural career progression. It would be nice to think you might get paid more the more experienced you are but I think that’s wishful thinking. Maybe picking and choosing jobs a bit more than I currently do. But it’s only two years so I don’t think that much is going to change in the space of two years. In terms of genre being a factor for AI, I do think some genres are going to be more susceptible to being put through AI. Some publishing houses might think, for instance we talked about crime fiction, ‘Oh, crime fiction is pretty straightforward, we could machine translate that and have someone post-edit.’ I don’t think they would do that if they bought a novel that was a literary fiction novel but again I think that these are all arbitrary terms. I don’t think you’re going to get a good AI crime novel where you would get a bad literary fiction one. I don’t think any of them would be particularly great. So it’s going to be interesting to see how it unfolds with things that are AI-generated, AI-assisted. They are arguably already AI-assisted if we are using things like online dictionaries, word reference, whatever.

JACKY: Thank you. Alex?

ALEX: I completely agree with what’s being said but I would just say as well that that sort of technology is really good at conveying information on the large part but when it comes to translating fiction, any fiction but especially suspense and crime, I don’t see AI being able to build up the rhythms in the text and the flow and the tension. I’m no computer technician but when I’m translating fiction, that’s so important and I don’t see something having the same kind of grasp of that as a human.

ROSIE: We had some discussions in our seminar group earlier where we all worked on translating the same text and then we compared. The level of discussion that went into the shortest of sentences, it was really interesting and obviously that can’t be replicated by a machine. I think a lot would be lost. It makes you think again about maintaining the author’s voice.

JACKY: I’m sure AI will get to the point of ‘Write a novel in the voice of …’ and out it comes. But let’s not go there, it’s slightly scary. Thanks again for the questions. We’ve got one from Caitlyn. It says, ‘Do you have a favourite UK Publishing House, one who is keen to take on translated Scandinavian fiction that you’ve enjoyed working with in the past? This is always difficult, isn’t it, because if you mention someone and leave someone out, it’s a bit tricky. But I just wonder, from your experiences, is there a house that you just think, ‘Oh great, they’ve asked me again.’

ALEX: I’m going to have to step out of this question! I have no books published with UK publishing houses so far, they’ve all been US, so I get to sort of step out.

JACKY: Nice, Alex. You get to sit back. Megan?

MEGAN: When it comes to crime fiction, I’ve always worked with Orenda, on all four of the ones I’ve done, a huge publisher of translated Scandinavian fiction. Another publishing house I really like in the UK that publishes a lot of translations and international non-fiction is Comma Press based in Manchester. Obviously also a Northern publishing house, which is just great all around. I heartily recommend all of their texts, they’re wonderful.

JACKY: That’s great. And Rosie?

ROSIE: I’ve worked a lot with Orenda Books as well. They do like Scandinavian fiction and they have very established contacts in the Scandinavian market. But again, when I think of who else I’ve worked with, it’s a real mix of different publishers, so I don’t think I could pick one in particular. I’ve had good experiences with all publishers and I think that once you find a publishing house, if you’re looking to pitch something, that does something like what you have, that would be the way to go.

JACKY: I am aware of the time and I don’t think we’re going to get through all the questions, sadly. Translators, if you have a chance to get in and type responses then please do respond to the questions. I’d like to return to some genre questions, if we might. We’ve talked about crime fiction but if we could put that to one side, it’s a wonderful genre, but what about other genres in which you’ve taken tremendous delight? What has it enabled you to do with language that other genres haven’t? If somebody comes along and says, ‘Will you take this job because it’s out?’ and you think, ‘Yes, wonderful!’ Alex, you talked about those different mental muscles. What would you choose?

ALEX: I would probably choose something that I haven’t worked on before. In terms of genre, I have really enjoyed working in horror. I don’t go in for gore or blood but I really love a kind of creeping sense of dread, even though that’s quite hard to live in for months, but I really like figuring out what makes that tick. Otherwise, I love playing with language, so I would also choose a strong sense of voice, whatever genre that comes in. I love getting under the skin of a text and trying it on for size.

JACKY: I love what you say, ‘trying it on for size’.

ALEX: That was a horrible mixed metaphor, getting under a skin!

JACKY: I love it. Rosie, is there a text that you would inhabit if you had a choice?

ROSIE: If I had the time, no deadline, no pressure, then something humorous. I think humour is a real challenge. So if it was for the fun of the challenge, then humour, definitely, because it doesn’t always translate directly. Different people in different countries laugh at very different things and express things in very different ways and I think that would be a real challenge. And you don’t see a lot of it, you do see some, but you don’t see a lot from the Scandinavian languages because I don’t think it always lands. So that would be something challenging and fun to work with. Whether I could actually make it work would be a different thing.

JACKY: I love what you say about having the time to be able to do that, just being in the text and not having that constraint that says, ‘Come on, come on, come on, there’s a deadline.’ And Megan?

MEGAN: Yeah, similarly, without a deadline. I would love to work on a massive fantasy novel, something with really strong word-building where you can just make stuff up. Like with all of the made-up words in Norwegian where you get to make up the alternative and have it fit in with the story and the overall vibe and setting. I would really love to do that. It’d be a challenge but it would be fun.

JACKY: Thank you. Maybe if Kate will allow me one more question because I can see the clock is not our friend this evening. We’ll stick within genre and this might be a bit of a tricky one. We’ve talked about the idea of when a job comes along and it’s paid and so that’s good. But of all the genres that are available, could you talk to us about one that you wouldn’t choose and why? Is there somewhere where you just do not feel that you want to set foot and why might that be?

ROSIE: For me, horror. I know Alex mentioned horror. Not my thing. I just get creeped out too easily. So for me that’s an easy one. I’m too much of a wimp.

JACKY: Okay. So no horror, no gore. Thank you. Alex?

ALEX: I struggle with gore as well. So, although I do love horror, if anything is too graphical, I struggle with that.

JACKY: You talked about humour, Rosie, and of course each culture has its own humour and I wonder also about gore and horror. Within the Scandinavian family, are the Norwegians gorier than the Swedes? Are the Danes quite mild? But first, Megan. We’ve not allowed you to talk about the genre that just makes you think, ‘Oh no, please don’t, not that. I don’t know if there is anything.’

MEGAN: I would guess maybe a full-on Mills and Boon romance. I would not be particularly keen to work on that but I’d probably work on anything.

JACKY: I get the sense from the three of you how much joy and delight you take in what you do. The three of you have been so open and generous with your responses. There’s been a lot of smiles as we’ve talked and I wonder, maybe one last question and it’s a really simple one. What is the most important aspect that you’ve learned about translating genre fiction since you began? Things you wish you knew when you started.

ROSIE: To ask questions. That goes for translating anything. When I started out I thought that if I asked questions I would reveal that I didn’t know things or that I was just an imposter, that I wasn’t qualified to have the job, and actually that’s not true at all. And having the confidence to ask questions or to say that you don’t understand something. That shows you do know what you’re doing because you understand that there are levels to things. So yeah, don’t be afraid to ask questions.

JACKY: Okay, ask questions. Megan?

MEGAN: I would say the exact same and also to take some time away from the text to do something else because it’s in those moments when you’re doing something really mundane or you’re lying in bed about to go to sleep that you suddenly remember the very specific word that you needed to use. So make sure you have some time off. Let your brain just sit and think for itself.

JACKY: Thank you. Alex, would you add anything different to this?

ALEX: Those are two top pieces of advice. I’d also just add, do whatever you can to allow you to come at the text as a reader rather than as a translator. For me it’s standing up, taking a walk, changing font sizes or fonts, printing it out, anything that can bring you to the text with fresh eyes because then you’ll get a real insight into what is working and what is not.

JACKY: Wonderful. I have so many more questions and I know we had other questions from the audience. Sadly, I feel we must draw this to a close. I hope we get a chance to meet again. Before I thank you individually, we should say that this session has been kindly supported by the Danish Arts Foundation, Norwegian Literature Abroad, the Swedish Arts Council and Arts Council England and we’re most grateful for that. Megan Turney, Alex Fleming, Rosie Hedger, it has been an absolute delight to be in your company this evening and to hear from those people who bring us texts that we take great delight in. May your careers be long and illustrious, may we always see your names there as the people who’ve translated and may that recognition of the translator just keep growing. It’s becoming more and more prevalent and it’s so important. Bless you. Everybody who’s joined us, thank you so much. Enjoy your translating and enjoy your fiction in translation. Goodnight everyone and thank you.

You may also like...

Watch ‘Meet the World: Translating Arab graphic novels’

In this Meet the World event, four writers and translators of recently published graphic novels from the Arab world discuss the translation process as well as identity, language and representation.

27th September 2023

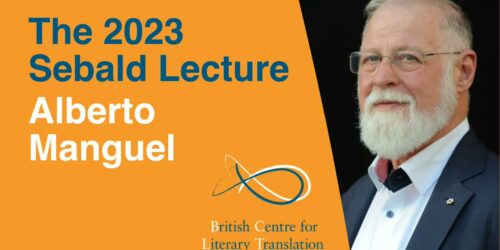

Watch the W.G. Sebald Lecture with Alberto Manguel

Our annual lecture on literary translation is available to watch online

11th May 2023

Five great tips for getting started as a literary translator

Thinking about a career in literary translation? International Booker Prize-longlisted translator Sophie Hughes offers some early advice

4th May 2020