Plot and structure are particularly important when writing crime fiction. The mystery must be unraveled at a steady and controlled pace, the clues neatly and deftly distributed, the denouement be suitably surprising, yet satisfying. Around this must be wrapped rich and believable characters in interesting settings.

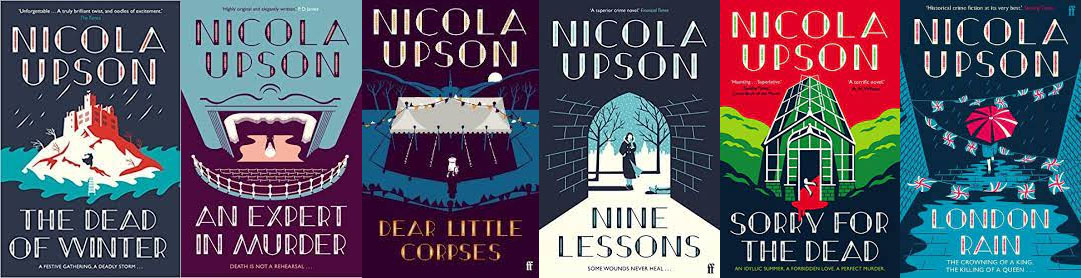

To help answer this question, we spoke to crime writer Nicola Upson on The Writing Life podcast. Nicola is known for her Josephine Tey series and tutors one of our crime writing courses – explore our online tutored courses here. In this edited transcript, she explains how her process has adjusted over time and discusses the unique requirements of the crime genre.

Nicola explains:

- How she moved from plotting before writing to letting the plot evolve as she writes

- Plotting when you need to

- The benefits of not plotting

- Characters vs plot

- Setting and plot

- Pacing the release of clues

- Controlling readers

How much do you like to work on a plot before you start writing? Do you plan ahead of time, or do you write as you go?

The early days

When I started out as a writer, I was less confident that I knew where things were going or that it would all work out, so I planned a lot. As I become more experienced, my confidence in my abilities grew.

Back then, it was quite comforting to me to be writing a crime novel, because at the time I saw that it had a fairly sturdy structure to work around. I’ve since gone on to believe that there are as many different ways to write crime stories as there are books. But the idea of that structure: the murder, followed by the preliminary investigation, followed by a second murder, followed by the denouement, helped me in those early books. These days that’s hardly ever the way the books work out.

Now it varies from book to book, depending on the kind of story I’m trying to tell. In the first few books in the series, when fiction still felt very new and daunting, I mapped out the beginning the middle and the end. It helped me to have some sort of roadmap of where I was going to end up – even if that bit in the middle changed as I went along.

Nowadays I do that less because I’ve become more confident with the books and come to know the characters much better. I tend to be a bit more fluid going into it.

These days it depends very much on the story and how the idea for that story evolves.

The turning point

The turning point

The turning point for me was The Death Of Lucy Kyte, in which Josephine inherits a cottage full of secrets. I wanted to write one of those mysteries that I love to read, one that twists and turns and you never quite feel you have a grasp of what’s going on. Sitting down to write when Josephine went to that cottage for the first time, I wrote a load of questions that she had to answer, mysteries to solve, clues that were planted even though I didn’t know what their significance might be. I didn’t even know whether everything that I was writing in those early chapters, would be left in.

It was amazing how much of it stayed. I solved the mystery with Josephine in real time of the novel. And that was a lovely way to work.

Plot when you need to

It doesn’t always work like that.

When I’m writing, there’s often a moment when I start to panic because there’s so much I want to include: so many scenes going on simultaneously in my head. There are all these moments I want to bring to the reader, but there doesn’t seem to be any kind of sequential order to them. They all seem to coexist.

It helps me to write down all the scenes I want to include and ask myself, what are the connections between those scenes? What is the single most important purpose of each scene? And that in some ways helps me find the order in which they should be told.

The other reason many of my books don’t evolve in a linear way is that sometimes they’re set in different time zones, so I find it very helpful to write one time in one sitting, even if, in the book, it appears more fragmented to the reader. It’s important to get yourself into one part of the book and stay there until you’ve finished that strand of the narrative.

Sorry For The Dead happens in different time zones: 1915, 1938 and 1948. It was important to get the 1915 scenes written completely in one strand because they were the bedrock of the whole book. I wrote it as a whole and then broke them up. They were the scenes the whole thing started from, so even though they appear in two separate blocks within the novel, they should still feel coherent and immediately transport the reader back to that time. I was living through those two parts in one go.

By the end of the book, all of those time zones have to layer up on each other and add something to the mystery that will be picked up in the next book. As such that had to be much more carefully plotted.

The benefits of not plotting

It can help make a book mysterious if the plot is a mystery to you when you’re writing it. And that makes perfect sense: if you don’t know what’s happening or going to happen when you’re writing, then the red herrings will be much more real for your reader as well. It’s less obvious which path you’re going to take.

In another book, I sat down to write an opening chapter, including someone who I thought was going to be just a peripheral character. By the time I’d finished writing that chapter, I knew that person would be at the heart of whatever went on to happen.

I’m less panicky about plotting now. In my early books, I was quite obsessive about knowing where I was going.

For one recent book, I just had a setting, a particular event from history I wanted the story to revolve around and a title. And that’s it. It’s the first time I’ve ever had a title I’m so attached to I just have to find the story that goes with it.

Let the plot evolve

None of my books have been particularly linear in the way they’re plotted. The plot tends to evolve. There’s something magical about the process that I still can’t quite explain.

As you get about halfway through the book, the basic storyline and the themes you want to work on emerge. Then new layers and new depths keep appearing and keep playing into your hands which is fantastic – you can’t explain it and you can’t bottle it, you just have to hope for it.

Characters vs plot

Many writers find that the plot needs the characters to do something, but sometimes that thing is something that character wouldn’t do.

This is less of a problem because of the way I write: plot stems out of character in the first place. Josephine Tey is a real-life person and there is always something real about her life or work that kickstarts the idea and that keeps her emotionally rooted to the plot.

Although she’s the lead character in the book, she’s not a policeman or an investigator or Miss Marple, so she has to be strongly connected to the narrative, but not in an obvious way. Starting with something real about her life helps to cement her into the plot.

Setting and plot

Then there’s always where I want to set the book. That comes very high up the list of priorities when I’m starting out. Setting dictates a lot about the plot: the sort of people who live there, and therefore the type of crimes that are committed.

With a bit of luck, the plots and murders come out of the setting and the world that those characters live in so there aren’t too many miss-beats or changes to be done later on, because the starting point for the story is the people who are going to live through that story.

Ultimately, the story has to be human. Readers have to believe in that world you’ve created. They have to think that those people they’re reading about are the same as living breathing people they meet in their everyday lives. If you achieve that, then you will hopefully carry off the idea of the story that you’re trying to bring to life. Put your characters at the centre of the story and let/make them own the story. I’m more interested in the types of emotions that might make you or I commit murder, it’s more interesting than someone who’s a psychopathic serial killer.

Pacing the release of clues…

It is a delicate balance. You have two types of reader: those who love to guess and love to have figured it out ahead of the book; and those who love the surprise. You have to cater to both.

When you’re writing the scenes down that you want to write, it’s important at that point to define what you’re going to reveal. You don’t want the information to come as an avalanche at the end, and you don’t want the reader to know the outcome in chapter two.

You have to choose early on what the significant reveals will be and when you’re going to give them to the reader through the book and make it as interesting as possible. Also, make sure there are plenty of themes and ideas in the book that spread out from the main idea.

There’s a puzzle and the guessing game and the pact you make with your reader and I try to play fair from that point of view.

Perspective is also important. You have to decide early on, who’s story it is, who’s scene each scene will belong to. What is the best perspective to give the reader what they need from that scene before you sit down to write? Whose eyes a scene is seen through is almost as important as the order of events?

Controlling narrative and information to manipulate the reading experience

There is a double narrative in lots of crime fiction. You’ve got two things going on: you know the beginning, middle and end, but you’ve also got the narrative that you want to present to your reader. You want to manipulate what they’re thinking at any given time within the book and you have to rely on sleight of hand, the character relationships and burying your clues in the most incidental of conversations. More than any other genre, with crime you’re trying to second guess the reader all the time.

I’ve written one novel that wasn’t crime. Stanley And Elsie is about Stanley Spencer and his creation of the First World War Chapel, his marriage and his life. Writing that book it made me appreciate how the crimes in a crime novel are key moments – the murder or the discovery of a body – and orchestrate and underpin the whole book. As a crime writer, you rely on those moments and I hadn’t appreciated that before I wrote my non-crime book.

When writing Stanley And Elsie there were times when I wanted the reader to feel certain things, but it’s not the same as actually manipulating what they’re thinking. That’s hard to do. And you’ll never know how well you’ve done until someone reads the book.

It’s always handy to have someone read your manuscript before you deliver it to your publisher. Sometimes the things that you think are obvious can slip through the net, and other things you think you’ve hidden well are writ large. It’s so hard for a writer to judge because you’re always so close to it.

Become the writer you want to be

We’ll get you writing with a tutored online creative writing course

Nicola is just one of our amazing tutors, for one of our courses. Explore all courses and tutors, including fiction, crime, non-fiction, poetry, historical fiction and scriptwriting.

You may also like...

25 essential tips for writing gripping crime fiction

Crime writers and creative writing tutors offer their crime writing tips to help writers of crime fiction, mysteries, thrillers and noir.

19th July 2022

How to write a novel – a step-by-step guide

This is a comprehensive, step-by-step guide to help you write your novel including advice and guidance from published writers

1st July 2022

Five top tips for writing historical crime fiction

From Nicola Upson, author of ‘An Expert in Murder’

2nd August 2018