Today is the day. You’ve committed to writing a novel, the novel, the story you’ve had burning and building in your brain for so long.

It’s a big project but you know that mountains are climbed one step at a time, just like a trip to the kitchen, so it’s not impossible, you just have to do it.

But you need to know how. You’re a reader – and possibly already writing – so you know that writing a novel takes more than an idea and a pen.

This comprehensive guide to writing a novel gives you the steps you need to start and finish your novel. Many of the insights and advice in this article come from our course tutors – find out more about our creative writing courses.

It is important to note that while this guide is comprehensive, there is no one single way to write a novel, so we have included steps that may not apply to all writers and all writing. As you learn what kind of writer you are and what kind of novel you are writing, you will know how to apply each of these steps and which, if any, do not apply.

You, the writer

Read books in your genre

Understanding the genre you want to write in is one of the most important parts of being an author and will help you write your novel. To do this, you do need to read a lot of books.

What books do you wish you’d written? What genre are they? Research and read ‘the greats’ in that genre. Make notes on these books – the good, the bad and the ugly.

Work through the books paying attention to the major story and style elements. Make notes on what you read, where it happens in the book, and how each element is linked to the others around it. Read online reviews and see what people say they like about these books. This will give you a good idea of how to write that type of book well.

The more books in a genre you read, the more you will start to understand the relationship between the various aspects of the story: character, plot, language, etc.

Read beyond what you like

Dutch writer Thomas Heerma van Voss says: “Read as much and as widely as possible.

“See how other writers construct their scenes, tease the reader, build tension.

“Don’t be afraid, especially when starting out, to steal or imitate – all arts begins with imitation. One of the Netherlands’ most famous writers began his writing career by copying out stories by Ivan Turgenev in an effort to master his rhythm and way of writing.”

Read writers who do not write like you

Trinidadian-British poet Vahni Capildeo says: “Make friends with writers who do not write like you. Swap books. Show each other work. Take the long view and the wide view.

Trinidadian-British poet Vahni Capildeo says: “Make friends with writers who do not write like you. Swap books. Show each other work. Take the long view and the wide view.

“Writing adds your lifetime to the lifetime of everyone else who has written or read, or who will read or write, including non-‘literary’ folk. All sorts of people work carefully or lovingly or effectively with words. You may find inspiration in a law report (ancient or contemporary) or a tide chart, or in an ‘unplayable’ play…”

Get the knowledge

Are you ready to write? Do you have the skills to take on the project and make it a success?

Consider taking a writing course to build and hone your skills. There are broad fiction and non-fiction courses, as well as ones that focus on many of the specific aspects of writing included in this guide.

We run a range of courses for writers with different needs:

- 12-week online tutored courses

- Short, self-paced courses

- Creative writing workshops

- Creative writing evening classes

Research

Critically acclaimed novelist Guinevere Glasfurd says: “Writers are often exhorted to ‘write what they know’. But what if your protagonist is a fourteenth-century nun? Or a drag queen from Kentucky (and supposing you, the writer, are not)?

Critically acclaimed novelist Guinevere Glasfurd says: “Writers are often exhorted to ‘write what they know’. But what if your protagonist is a fourteenth-century nun? Or a drag queen from Kentucky (and supposing you, the writer, are not)?

“Start by reminding yourself why you want to tell the story. What drew you to it? What interests you about it? Is there anything unresolved? Something that niggles or snags? What other questions come to mind? Identify the gaps in your knowledge. Is your character a doctor? Of what? What is their specialism? Your research might set out to answer quite basic questions or it might be something more forensic, requiring you to piece together disparate sources, or conflicting opinions, before you can form your own view.

“Research can be frustrating; sometimes the archive is silent, the answers are not there. There’s a reason for that and that should spark other questions. Research can also be enormously rewarding. It can, and likely will, reveal something unexpected. It is important to remain alert to that, to be attentive and open to surprise. Research is an iterative process. Research a bit, write a bit, research a bit more. Allow your writing to remain fluid at this point, open to question, encouraging of further enquiry.”

Access our Early Career Writers’ Pack on Research

Read Guin’s full article – which includes 8 places to do your research.

Don’t prescribe your writing style

Thomas Heerma van Voss says: “Don’t think: I am going to write something ‘literary’, so I’m going to have to use all kinds of metaphors, complex syntax and (semi-)philosophical musings to tell my story. Write the way you speak.

Thomas Heerma van Voss says: “Don’t think: I am going to write something ‘literary’, so I’m going to have to use all kinds of metaphors, complex syntax and (semi-)philosophical musings to tell my story. Write the way you speak.

“Never start by thinking you have to write something complicated or deliberate, or because you think you have to develop your own sophisticated style, but simply because you want to tell a particular story or describe a specific scene. Your style will appear all by itself. It always does. All text betrays the writer.

“For example: for years no one knew the real identity of the writer behind the successful Dutch pseudonym Marek van der Jagt. Eventually, a computer identified Arnon Grunberg as the author on the basis of language use and the length of the sentences. Style always reveals the DNA of an author.”

Define what kind of writer you are: Pantser or plotter

‘Pantser’ – a writer who has an idea for a story (maybe just a scene, a ‘what if?’, a setting or a person) and just starts writing, writing “by the seat of their pants”.

‘Plotter’ – a writer who has an idea and works out what happens, when and how – and how it all ends. Many plotters will then write all this down and plan it into chapters and even detail what needs to happen in each scene/chapter before sitting down to write.

It is important to note that many writers will be somewhere in between these two poles. UK science fiction writer Peter F Hamilton says that he will spend six months just working on the world and the story idea before starting to write.

Many writers also like to have a plan, but acknowledge that, as they get into the story’s telling, it can veer off in new and unexpected directions. So, even if you have a plan, be flexible.

Decide how you’re going to write your novel

Some writers still use pen and paper – especially for first drafts. Others use old-fashioned word processors – as they say, it reduces the distractions of modern computers, especially in the internet age. Some writers have even written novels on their phones. Most, however, use a computer and software such as Microsoft Word (for planning many also use Microsoft Excel spreadsheets to help organize and structure chapters).

Microsoft Word – and today’s Microsoft Office 360 – costs money, but there are free alternatives, for example Google Docs. This cloud-based software has many of the formatting options of Word and, because it’s in the cloud, you’re never in danger of losing your work.

Other software created specifically for writers has been created, and you may find you like one of them, for example:

Access our Early Career Writers’ Pack Method

Get the right technology

From the quill to the spellcheck, technology has always played an important role for writers. Today digital technology is helping writers to research, plan, write, improve, share and store their stories, for example a piece of software called Scrivener, designed specifically for writers.

Read our article 11 Digital Essentials Tips for Creative Writing for advice on hardware and software to help you:

- Plan and write (Scrivener)

- Manage your project (Trello)

- Record ideas

- Store your writing

- Set up a comfortable workspace.

Writing advice: Don’t Create in Front of a Computer

Icelandic writer Valur Gunnarsson, says: “Like many or most writers, I was in lockdown mode before everyone was. And it had taken me a long time to learn how to manage my day. At first I treated writing a book like I was taking an exam, working long into the night until the point of exhaustion and getting up in the late afternoon, usually to redo what I had done the previous night. But this is no way to live or, indeed, to write.

Icelandic writer Valur Gunnarsson, says: “Like many or most writers, I was in lockdown mode before everyone was. And it had taken me a long time to learn how to manage my day. At first I treated writing a book like I was taking an exam, working long into the night until the point of exhaustion and getting up in the late afternoon, usually to redo what I had done the previous night. But this is no way to live or, indeed, to write.

“You see, writing should take up very little of a writer’s day. Sitting in a room in front of a computer screen is not the best way to be inspired. Worse, most ideas that you manage to squeeze out tend not to be very good, inviting yet more long hours of rewrites.

“The creative part of a writer’s day should go into thinking about the work in question. This can be done anywhere, ideally when getting exercise often missing during times of lockdown or writing. Go for a walk, go for a swim, even step hamster-like on a treadmill. While doing just that, think about what it is you are trying to say. That way, when you do sit down in front of the computer, you know (almost) exactly what you want to be doing.”

Create your writing space

Writers need a space that’s conducive to productivity. Because everyone is different, this will vary from writer to writer. This section, like many others, will guide the principles of best practice, the desired results, rather than define exact desk heights, types of drink or music.

Much is written about writers and their writing spaces, because they can massively impact the writer’s productivity. Whether simply rooting out noisy distractions, or meticulously manufacturing that specific yet indescribable ambience, many will work hard to create their perfect writing environment. Roald Dahl famously – as well as many others – write in their shed, from Virginia Woolf and Philip Pullman to our own Julia Crouch. What is your ‘shed’?

Here are some things to consider when setting up your writing space:

Distractions

-

- It is important to maintain the flow states that we all seek: when the ideas are flowing and the words arrive on the page as if piped in from the divine. It is also important that thinking can happen without interruption, allowing thoughts to probe, imagine and build.

- Avoiding distractions is essential, especially in the omni-connected internet age and our ever-busy lives of children, work, friends, pets and chores. As such you should seek and/or build a space without distractions.

- As well as the space, you should let your friends and family know that when you are in that space (or during certain times, or ad hoc) you would prefer not to be disturbed. This means that not only will you not be disturbed, but you can work knowing that you will not be disturbed – not writing in fear of the calm being broken at any moment, an anxiety that itself can occupy our brains and inhibit creativity

Equipment

-

-

- Define what you will need to allow you to write for an hour or more without disruption – and ensure that it’s at hand. The obvious essentials are writing equipment: do you have your laptop, PC, tablet or pen and paper? Or some combination of these? Beyond this, do you have water, tea-making equipment, snacks, music player, notes nearby?

-

Comfort

-

-

-

- It is important that your desk setup is comfortable. This is not only so that you are not distracted by discomfort, but because it is important for ongoing health that your workstation is ergonomically designed to reduce the chances of strain injuries, back pain etc. If your workstation is comfortable, you’re also far more likely to want to work in it, and return to it.

- Relating to this, consider:

- Chair (back support, height in relation to desk)

- Desk (height)

- Lighting

-

-

While a good writing environment is powerful, it is important to add that we can write anywhere. Don’t make your writing routine restrictive, don’t assume that it’s the only place you can write. While you may prefer the quiet of your shed, you may find trains or cafes work too.

Preparing your novel: story and plot

Grow your idea

Award-winning Trinidadian-born British writer and NCW course tutor Monique Roffey says: “All novels start with a grain of sand, an idea. But, in order to turn that grain of sand into a pearl, time is needed. Pearls grow slowly. The good news is, time plus active research is a winning formula. Don’t just wait for your idea to grow by itself, also do some research.

“Books are made from other books, and so read, read, read around your subject. Let your idea mate with other ideas. I own a very large cork board that sits above my desk. My novels, as I research them grow visually, especially, as I start to do research. I find ‘looking at my novel’, as it starts to grow, extremely helpful. It makes me think, it keeps the novel alive, it gives the novel images to work from. Images are scenes.

“I grow my novel for some time, by reading and creating images until the novel starts to write itself before I’ve even written a word.”

Writing advice: Conflict

Creating a clear central conflict will anchor your plot and give your narrative focus. If you’re a first-time novelist or new writer, look to thrillers, fantasy or adventure stories for examples of compelling good guy versus bad guy conflict.

Conflict is good because it can make motivation clear.

Refine, clarify and nail down your story idea

‘Idea’ can be an ambiguous word within writing. What is less ambiguous is that, at the start of the whole process, you will need some sense of what your novel is going to do, how and even why? What is your story, and what does it mean to the characters/world? This is because we need some sense of where we’re heading when we write: where are we driving the story? Even if the direction changes, we must start with that ‘north star’.

There are some universal stories, and you may find them useful as starting points to help describe your particular idea, for example rags to riches, love story, succeeding against the odds, rebirth, voyage and return. Some novels are more than one of these, when including subplots.

If this is still vague, try defining the ‘idea’ of some of your favourite novels.

Now do the same for your story. See if you can condense it into two or three sentences. Now expand this to about 500 words. Keep this and refer to it if you get lost, have writer’s block. You can also amend it if the story changes in the writing process.

Writer advice: Stepping stones

Writer advice: Stepping stones

Writer and NCW course tutor Monique Roffey says: “Most writers have, at the very least, sketched their story out before they start writing. This isn’t a hard and fast rule, though; but it’s one that works for many. To just start writing and ‘fly by the seat of your pants’ is almost asking to fly your plane into the ground.

“Try working out the basics of your story first: beginning, middle and end. Look at Freytag’s Triangle and have a think about your rising action, climax and falling action. Do you have the five parts of the triangle mapped out? They are the minimum you need to be starting with.”

Structure your novel

Once you have a clear idea of your story concept, you will need to define an essential aspect of how you’re going to tell it. This is the story’s structure – what happens when. While this may seem simple if not obvious, the structure must be carefully considered to ensure that the story makes sense as well as compelling the reader to read on. There is no specific ‘best structure’, but there are devices and methods to guide yours.

At the highest level, most stories have a beginning, a middle and an end. This has been translated into the three-act structure:

- Inciting incident

- The journey, rising action, challenges

- Resolution

Novelist and NCW tutor Ian Nettleton explained on our podcast, that structure can also be driven by genre, for example, crime fiction tends to have quite a formulaic structure, while more experimental works may buck this trend.

Consider the following devices that can be used within the wider structure to compel readers throughout and deliver a satisfying end.

- What is the setting? Where are we, what’s going on and to whom?

- The promise. Suggesting what the story will deliver if the reader reads on

- The trigger/inciting incident. Something happens or changes and something needs to be done about it

- The quest. What must be done?

- Raising the stakes. Make the quest more important, weigh it down with potential repercussions

- Heighten the drama with surprises and twists by subverting their expectations

- Critical choice. The protagonist commits to doing something

- The quest reaches its peak; the culmination of the action

- Things finally start to go the protagonist’s way for once (though you might choose to subvert this and have things get even worse)

- The results of the climax and reversal; delivering the promise.

While you don’t have to stick to this structure, you might want to see how your story idea maps onto this, and what might be happening in your story to deliver these.

Other structural story elements that you can use, include:

- Refusal of the call

- Meeting the mentor

- Crossing the threshold

- Tests

- Approach the innermost cave

- The ordeal

- Reward

- Road back

- Ressurection

“Usually, I have about 20 scenes imagined before I start any book,” says Monique Roffey. “They are like stepping-stones and I like to have them on cards pinned to my board. There’s nothing more satisfying that ripping these cards up as you write the scene. Many writers plan much more carefully and precisely, including Hilary Mantel. Most genre writers plan very carefully indeed. But doing a lot of research and having a plan or plot outline before you write is one way to make sure you are more likely to succeed when you do start writing your first draft.”

Access our Early Career Writers’ Pack on Structure

Listen to our How to Structure a Novel episode with Ian here.

You can go direct to the RSS feed here.

Writing advice: Don’t divide into chapters at first

Once you’ve created your structure, it may be tempting to divide it into chapters. Refrain.

This is because chapters can start to become prescriptive and therefore restrictive, not least because the chances are high that whatever you write in your first draft will get mixed up, divided and added to other sections, or just removed.

Don’t worry about sectioning your story into chapters until you’ve completed your first draft – during which you will probably feel where they should go as you write.

The best time to correct flow, pacing, and logic is once you’ve written your story. Only now should you decide how to structure the chapters so that they not only complement but enhance the reader’s journey.

Start your novel in medias res (in the midst of things).

In medias res is Latin for ‘in the midst of things’. By focusing on action and activity, you will grip your readers more than if you have pages and pages of back story, scene setting, description or world-building. All of this may be important, and you’ll get to it, but it’s more important to grip your reader first. And by making them feel like they’re in the middle of something, they are more likely to be gripped.

Choose a world you want to spend a lot of time in

Novelist, Neil Gaiman advises us to set our novel in a time and place where we want to spend a lot of time in. He says this, for two reasons:

- If you want to spend time there, it’s more likely that your readers will also want to spend time there “Your novel will require your readers to immerse themselves in a specific world for the hours that they spend reading.”

- You will have to spend a lot of time there as you write your story “[Writing] will require you, the author, to immerse yourself for weeks, months, and even years in this world.

He also adds: “Don’t overstuff your novel with location changes.”

Plot your novel

Story idea, structure and plot have an alchemical relationship – sometimes scientific, sometimes ‘magical’.

- Plot: the series of events that make up your story, when they happen and how they’re linked

- Structure: the overall design or layout of your story

While we have put plot after structure in this list, this is not a rule of thumb. This is because writing and revision may drive changes to one or other of them. For example, your plot may stay the same, but you may decide to change the order in which you reveal certain facts.

If you have worked up the structure of your story, you need to outline the specifics of the plot. For example, your story might be, ‘Mary is kidnapped and taken into space. Ben goes after her’. The plot needs to define how these things happen. ‘Having been mistaken as someone else because of a costume party, Mary is kidnapped. Only after not being able to get in touch with her does Ben discover the facts’.

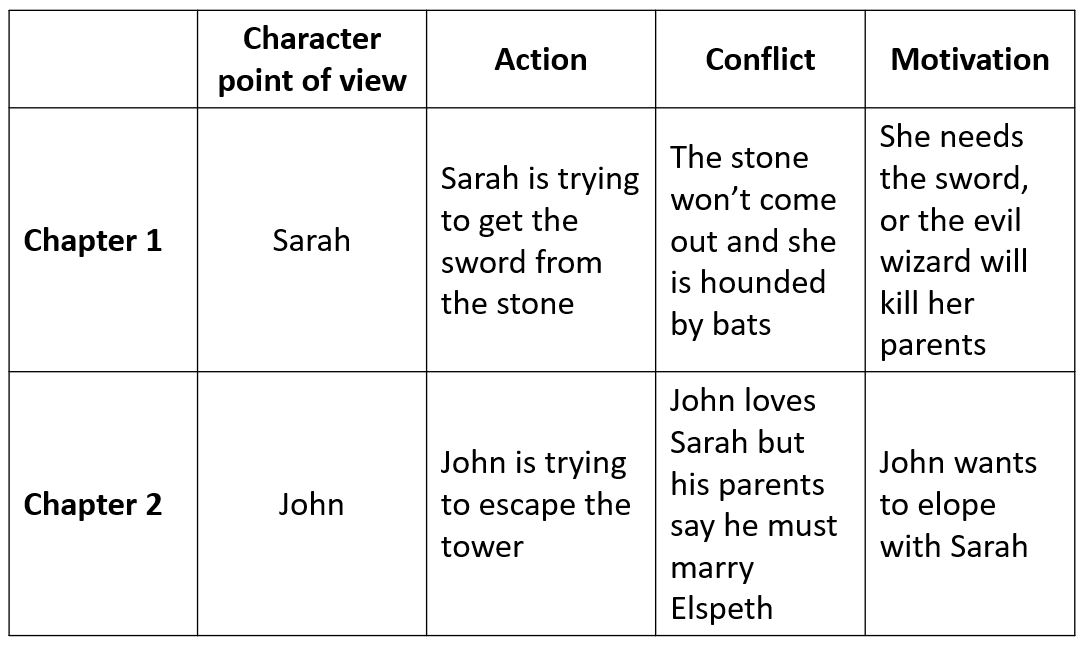

You may find that using a table or spreadsheet helps to organize your plot and structure. For example, by having columns on ‘conflict’, ‘purpose’, or ‘motivation’ you will ensure that sections a directed and don’t become meandering. Many new writers find this valuable as their early chapters can often be too heavily focused on exposition and world-building which slows the pace and delays the inciting incident or conflict.

Access our Early Career Writers’ Pack on Plot

Novelist Ashley Hickson-Lovence discusses the relationship between story and plot in our podcast.

You can go direct to the RSS feed here.

Introduce subplots

Secondary subplots are not essential, and there are many great novels with singular plots. However, subplots can provide readers with interesting counterpoints and distractions from the main plot. For example, while the main story might be of the ‘save the world’ variety, there might also be a love story or journey and return subplot for one or more characters.

For each subplot, define:

- Inciting incident

- Journey and challenges

- Crisis

- Resolution.

Create and explore your characters

Arguably, characters are the most important part of story. Humans care about what humans do, and they’re active so their actions will drive the story.

Readers experience the world of your novel through your characters, and whatever happens in your story will impact its players, so we’re invested in both.

As such, there’s a lot to cover with character and we have created lots of handy tools to help you create compelling characters.

Even if you don’t include much physical description of your characters in your book it can still prove helpful to have an internal image of the people you’re writing about.

Access the physical description template in our Early Career Writers’ Resource pack

It is useful to dive into a character’s past. Understanding where they came from can inform what they do in the present. Again, you don’t have to reveal all – or any! – of this information explicitly to the reader, but having it in the back of your mind can add layers and depth that would otherwise be missing. Here’s an example backstory template you can download to get started.

Access the character backstory template in our Early Career Writers’ Resource pack

Other character resources:

- Article: Developing characters

- Podcast: Creating Characters With Michael Donkor

- Video: How Sarah Perry develops characters

Establish the setting

The setting of your novel is important because it provides the reader with the story’s context. By developing and communicating a detailed and compelling setting – whether real or imagined – you help the reader understand the world of your characters and embed them in it. A rich setting will of course also help your reader to visually imagine places and people.

To help build your novel’s setting, provide information about time and place using the senses: sights, sounds, and smells as well as how things physically, mentally and emotionally feel.

This is particularly important if you’re readership is unfamiliar with the setting, for example, far-flung places or imagined worlds or times.

Speculative fiction writer China Mieville is a master at creating interesting settings, but also bringing them to life through the senses. For example, his novel, Perdido Street Station is set in an imagined world of steampunk technology and magic. Within this, the sprawling city is almost alive with its parasitic inhabitants and layers of filth and rubbish as it’s reused and discarded.

You might do the following:

- Make notes on interesting places you’ve been

- Write a fictional travel diary of your own visit to the place

- Collect photos or illustrations to create a collage of setting ideas

- Create a timeline for the history of your setting (Peter F Hamilton’s huge Night’s Dawn space opera trilogy includes a 700-year history that helps to explain the technological progress to the 27th century).

Read: Turn your setting into a character

Create an outline

There are many forms of outline, from a one-page written document to a comprehensive visual representation of the plot using diagrams and/or tables.

If you’ve completed all of the preceding steps in this list, you’re ready to create your outline – in fact, you’re almost there.

-

-

- Distill your novel’s idea into one sentence

- Decide on a story structure for your novel

- Get to know the characters in your novel

- Flesh out your novel’s plot

- Decide on the setting for your novel

-

All that remains is:

-

-

- Synopsize the chapters of your novel.

-

Bring this together into your preferred format.

Choose your book’s point of view

How you tell your story – who’s viewpoint you use – has a big effect on how your novel will be received by readers.

- First person – ‘I’, where the narrator and protagonist are the same

- Second person – rare and difficult

- Third person – a story told by an invisible/non-existent narrator

Here’s how to choose which point of view to choose:

- How much distance do you want to put between the reader and the narrator?

- How much information do you want the reader to have?

- How trustworthy do you want the narrator to be?

- Do you need to use multiple viewpoints throughout the story?

Writing your novel

Establish a writing routine

Most professional writers will have a routine designed to make them as productive as possible. For those of us who have full-time jobs, it can be a little harder, but arguably, all the more important to make the small amount of time we have count.

A set writing routine will help:

- Motivation

- Improve your writing

- Reduce procrastination

- Finish your novel!

Monique Roffey says: “Everyone ‘feels like’ writing at different times of the day. While I understand not everyone gets the luxury of using their favourite hours to write, my advice is to try and arrange your working day around favoured hours, often early in the morning or late at night.

“When does the muse most likely strike? For me, I’m best first thing in the morning, while still unguarded and still full of dreams. I write then, and I write till lunchtime, and then I’m done. I write on my laptop and l always have.

“One writer friend writes on her phone, with one thumb, on the way to work. Another friend writes best at 3am, but then he’s an insomniac. Find your time and place and rhythm and try to keep to it and then, slowly, slowly you will find you have writing in your life, as a habit.”

To build your writing routine, define the following:

- What time of day works best

- See Create Your Writing Space above

- Which project you’re going to work on

- What you want to achieve with each session before you start (that way you’ll know when you’ve finished). This might include a word count

- Some people find it valuable to write what you want to do next, when you finish each writing session. Picking up where you left off and getting back into the zone can be a challenge, so a note of what you want/need to do next can help.

Listen to How to Develop a Consistent Writing Habit with Tim Clare

Writing advice: Write every day

Amer Anwar says: “Writing, like any other exercise, gets a little easier the more you do it. Not that the writing itself is easier, it’s just that you become more accustomed to doing it. You’ll be more adept at getting into a writing frame of mind and jumping right back into your story.

“Like running a marathon, it takes regular training to be able to tackle such a mammoth feat. Writing every day flexes your mental muscles and whips your imagination into shape, for the long and arduous task of writing a novel. And, just like a marathon, it’ll still be hard but working at it every day will make it feel just that little bit easier.”

Grip your reader

Crime novelist and NCW tutor Julia Crouch explains how to grip your reader:

- Viewpoint is your friend

- Stories can be told from the point of view of many different characters, each with their own take on the events. Choose who is doing your telling very carefully, work with their voices, character, secrets and lies, reliability or lack thereof, and the spaces between different points of view.

- Hold back

- Your reader doesn’t need to know everything, all at once. In fact, in most cases, the less you can tell them the better. Just give them what they need to know for your story at that particular time.

- Structure is important

- There is a reason that screenwriting gurus bang on about the three-act structure – setup, confrontation and resolution – and that’s because it works.

- Time is not a fixed continuum

- Back story doesn’t have to just sit in the past. While it is being read, it is the present of your story world, as much as the current day scenes are. The reason it is there, though, is to provide causality – to show why things are happening in your present, and that is the engine of any plot. You can start with the back story, end with the back story, distribute it evenly throughout your narrative. Just put it in the place that serves you best.

- Twists

- It is usually important that the reader can’t predict what’s coming, or work out the resolution too early. Holding back, as in point 2, above, helps. But twists that arise out of the narrative are most useful, and even expected in certain sub-genres. A twist has to earn its existence, though. It can’t rely on red herrings, or outright lying by you, the novelist (although unreliable narrators, handled carefully, are permissible). If the reader closes the book away feeling cheated, you’ve lost.

Engage the theatre of the reader’s mind.

Thomas Heerma van Voss says: “Writing is all about engaging your readers. By surprising them, by making them feel connected to your characters and what they go through.

“No matter what you write or how strange your story might be, make sure the reader believes it. And that it keeps you interested, too.

“This is all down to style. Real-life events can become implausible if not described well, and strange concoctions can come across as perfectly logical in a well-crafted story. This is often the essence of good writing.”

Raise the stakes

What is at stake in your novel? The planet, a life or just the love of a good person? Define the stakes:

- What does the character stand to lose?

- What do they stand to gain?

- What do they need to do or get to gain and not lose?

- What stands in their way?

- What are they risking in trying to achieve their goal?

Whatever is at stake, increase it or introduce other things that might now be at stake. This will help to grip your readers, drive them on, as well as deliver greater relief and satisfaction when the resolution comes. Use the list above to raise the stakes at each stage, ie:

- They now stand to lose more

- They now stand to gain more

- The thing they need to do or get has now become harder

- More things, worse things, harder things stand in their way.

Make the predicament appear hopeless

Similar to raising the stakes, making the situation seem hopeless is another great way of increasing the excitement and sense of satisfaction in the final resolution when it comes. Novelist Angela Hunt refers to this as The Bleakest Moment.

How does the protagonist finally solve the problem?

Well, put some new and unexpected obstacles in their way.

Then, at last, remove it.

Many stories lead us down one path of solving the problem, only to have it removed or not work, before introducing something we’d forgotten about to finally solve the problem.

Leave readers feeling satisfied

Novelist Eva Verde says: “For some lucky writers, the ending appears to them long before the story even makes it to paper. For others, (me) the end is more a black hole of avoidance.

“Whatever your writing flow, endings are as crucial to nail as those first opening pages – and just as tricky.

“Tie your endings up too neatly and the reader will feel that they’ve been done a disservice. Leave them too ambiguous and, well… same. Even when I don’t have a concrete vision of how my story finishes, I always stay focused on what I want my ending to achieve.

“As writers, we’ve the glorious privilege of shapeshifting worlds with our words; everything is ours to edit and rearrange. Often, it’s in the working backwards, that we’re better equipped to tie up and intensify our story threads, so having even the loosest sense of an ending helps.

“Try out some different endings on objective yet trustworthy friends (they’re hard to find, so love and treasure them). Often, a different take can open new creative directions, so let your ideas grow. Sometimes the most brilliant breakthroughs happen when you’re showering, lunching, queuing in Tesco. Thinking time is also writing time.

“Question how your story might develop if you were an observer, rather than the creator. What could be foreshadowed that your reader can draw conclusions from, without delivering a heavy-handed finality to your ending?

“A satisfying resolution is important but note also: coincidence. In writing, even the most innocent of coincidences can feel the most contrived, particularly when they’re plucked from nowhere at the very end.

“Consider the build-up to this finish, all the tension and feelings you’ve already created along the way. Relinquish your controlling tendencies – allow your reader the pleasure of doing some of the work.”

Access our Early Career Writers’ Pack on Endings

Bash It Out

Writer Amer Anwar says: “Hemingway is quoted as saying, ‘The first draft of anything is shit,’ so don’t expect yours to be any better. The most important thing is to keep going and get to the end. Don’t worry about editing for now; the first draft is just for you, a guide. Once you’ve completed it, you’ll have a whole novel. Then you can start worrying about editing and revising it.”

Writer and NCW course tutor Monique Roffey says bash it out: “A novel is, on average, 90,000 words. That’s 1,000 words a day for 90 days, so don’t dilly dally, bash it out.”

The initial writing of a first draft is the hard work (if not the difficult work) but it’s only a part of it, so getting it done before the revision stage is essential.

“Aim for 1,000 words a day for 90 days. If that’s too much, then go for 500 a day for 180 days. That’s 3-6 months’ work, that’s a very very energetic and satisfying way to manifest a first draft. Set your alarm clock to an hour before work or two hours before work, get up early and sit to your desk, and then let yourself go.”

The first draft has a role in defining what the final story becomes, so don’t tinker too much at the planning stage and don’t agonise too much; get the first draft written, then you can start to revise and tinker.

Amer adds: “I struggled with this at first, but then switched to writing longhand, pen on paper. Old fashioned, I know, but it forced me to keep moving forward. There’s only so much you can edit longhand, so it made me just plough on.”

Don’t write and edit at the same time

Monique Roffey says: “Write. Let the muse strike and write for your life. Take hours if you need to. Then go for a walk. Leave your words to cool. Hours, or even days later, come back and tidy it up.

“Trying to do both at the same time is a recipe for what writers call ‘writer’s block’. It’s like driving with the hand brake on. Just like a good tennis player can play with their left and right hand, so a writer needs to master writing and editing but they are very different things, one creative, the other more pragmatic and literal.

“You don’t want to be editing every sentence you write. You need to edit your sentences sometime after you write. Otherwise, you can soon become gridlocked, fraught with anxiety over every word. Write; let your fingers fly at the keys. Think of the grammar and spelling and structure of each sentence later.”

Don’t cling to the initial idea behind your book or story

Thomas Heerma van Voss says: “Don’t cling to the initial idea behind your book or story.

“The final version will always be different from what you had in mind at the start. And there’s nothing wrong with that. In fact, it often leads to new insights, the kind you would never have thought of otherwise.

“All my stories and books only ever start to take shape after I am about halfway through writing them, and sometimes not even until the editing stage. Try not to judge your text on the basis of what it ‘should be’ but on how it is, how it comes across, what works and what can be improved.”

Writer’s block

Many writers suffer from writer’s block, but there are steps you can take to tackle it. Award-winning writer Eliza Robertson says:

- Stop thinking about what others will think

- Exercise

- Recognise distractions – both good and bad

- Try to turn rituals to your advantage

- Use reading to break the block

- Type out a passage from a random book on your bookshelf

Read Eliza’s full article: Eight Tips to Cure Writer’s Block

Relax; it’s not a race

Monique Roffey says: “I journeyed home the other night, on the Central line, with a well-known writer who is about to publish her third novel. Her last novel was published seven years ago. “It took its own time,” she said. “I had to relax into it.” And, of course, we have the example of Arundhati Roy’s massive twenty-year break between novels.

“It’s just not a race, it never is. Novels take their own time. They refuse to be rushed. They need research; they need drafts, they need downtime. They need editing. They need a lot of time and space and you need to practice your craft first and be up to it. First practice fiction, then try small things/stories, in your own time, and your own way. Join a peer group of fellow scribes. Open up to constructive feedback, grow and learn and apprentice yourself for a couple of years, then settle. It’s not a race. Write what you want in your own time.”

After you finish your first draft…

Take a break

Writer Amer Anwar says: “OK, so you’ve completed the first draft. It wasn’t great (no surprise there) and you’ve edited and redrafted the whole thing, probably several times. You’re pretty pleased with it.

“Now is exactly the time to stick it in a drawer, or in a folder on your hard drive, and leave it for a while. How long? The longer, the better. I left my novel alone for a whole year, through circumstance rather than choice, but when I did go back to it, I was much more objective. It was almost like reading someone else’s work, which made me a lot more ruthless in finding faults and cutting or fixing them.”

Monique Roffey says: “An artist usually makes sketches or a sketch of what she or he plans to paint or make, especially if it’s a long piece of work. So too, the writer should draft and make sketches.

“Plan and write a single draft, aim to get it finished rather than for it to be a perfect end product. That’s because it’s only the first draft or sketch. Let your first draft settle; give it six weeks before you read and edit it in hard copy form, then make notes and start draft two, and likewise draft three.”

Revision: rewrite and redraft

You must revise your novel’s first draft. A first draft is a raw and unfinished document, that will need layers of amends, words, line, paragraph, sections and even whole chapters may need to be moved and changed.

- Step 1: Read through your first draft and make notes

- Step 2: Consider the timeline, pacing and structure – does it all hang together and make sense

- Step 3: Ensure that all characters feel rich, real and alive – build out where necessary

- Step 4: World-building. Ensure that your world – real or imagined – has been built out

- Step 5: Tighten pace and dialogue at a scene-by-scene level

- Step 6: Copy edit for typos, literals, punctuation and grammar.

Here are some questions you might want to ask of your work-in-progress, inspired by screenwriter and tutor, Douglas Dougan. Start at 1, apply to your text, move on:

- Understandability – does the story make sense / is it complete?

- Structure – do the mechanics work / is it character that flips those mechanics?

- Character – does each character have a journey / is it consistent?

- Conflict – is there conflict? / is it enough?

- Dialogue – does it communicate character/individuality?

- Theme – what is your piece really about?

Above all strive for unity, everything working together to reveal your story’s beating heart.

Writing advice: Revision

International Literature Showcase-selected writer and author Mary Paulson-Ellis says: “My debut novel, The Other Mrs Walker is notoriously tricksy. Two narratives, multiple timelines, objects traversing past and present. The agent who took it on wanted changes. I anticipated a long list. Instead, I got three sentences: let go of the architecture; follow the objects; change the ending. I was disappointed. This was not the intricate set of notes I’d been hoping for. Nevertheless, I applied her suggestions to my text.

“Amazingly all its problems became suddenly clear, along with their various solutions. At first, I thought the agent was a witch. Then I realised after forty years in the business she had learned to fix on the heart of the thing and direct her writer straight to it. She trusted me to do the rest.”

Editing

Assistant editor Hannah Chukwu from Penguin Random House explains how the editing process works.

This video shows how you can make real improvements to your first draft through simple self-editing techniques.

Listen to: The value of editing with Georgia de Chamberet

Access our Early Career Writers’ Pack on Editing

Writing advice: Never compare

Monique Roffey says: “It’s fatal to compare your work to that of others. Never compare your journey to anyone else’s and your writing style to that of another. Having a competitive streak, or a mindset that is constantly trying to compare and assess your work to others is unhelpful. While there may be the ever-hoped-for book deal as a goal, really, in my experience being goal orientated about writing is anti-creative. It doesn’t help. It puts the cart before the horse.

“Instead, make the work, quietly, and let the work develop. Keep it sacred, stay humble and conscious and instead be conscientious and regular in your writing. One day, over time, something will come of your pages. Show it to an editor, get some sound feedback and then write some more. A writing career is a slow, long haul, career; it suits bookish, studious types who like reading. Nerds. Don’t look over your shoulder. Be the nerd that you are, feel into it, and write your own thing. If a person in your group does well, fine.

“As Gore Vidal said, famously, ‘every time I hear that a friend has done well, a part of me dies.’ This is funny and true, especially true of writers. Stay cool. Wish your friend well and keep writing and never worry or compare your work to theirs.”

Get feedback from beta readers

Amer Anwar says: “After all the work you’ll have done on the book by yourself, it’s a good idea to get some other opinions on it. This is hard.

“What you need to do is find, say, three or four people whose opinions you trust and let them read it. Make sure they’re people who read a lot, preferably the genre you’re writing in, and who won’t simply tell you it’s great because they don’t want to hurt your feelings.

“I picked a few friends that I knew would like the type of book I’d written and specifically told them to focus only on anything they didn’t like or that they felt wasn’t working and to let me know. I made it clear that by doing this, they’d be helping me improve the book, which was all I wanted. Receiving any negative feedback is difficult but it’s very necessary.

“You don’t have to accept all of it. Some you’ll know is right and, if most of your readers comment on the same parts, then you’ll know there’s something that needs fixing. If it helps to make your book better, it’s definitely worth it.”

Level up

Once you’ve reviewed and revised your novel’s first draft, you may see that you need to build on certain skills: characters, plotting, structure, dialogue, world-building etc.

Explore courses, workshops and mentorships that will help you build the specific skills you need.

For example, we run a range of courses for writers with different needs:

You may also like...

17 tips for writing creative non-fiction

Writers and editors give their advice on writing non-fiction and tackling its challenges.

30th July 2022

25 essential tips for writing gripping crime fiction

Crime writers and creative writing tutors offer their crime writing tips to help writers of crime fiction, mysteries, thrillers and noir.

19th July 2022

5 common scriptwriting mistakes (and how to fix them)

Molly Naylor shares her top tips and techniques

16th March 2022