Sawad Hussain is an Arabic translator and litterateur who is passionate about bringing narratives from the African continent to wider audiences. Here, she reflects on her experience during her Visible Communities virtual translation residency with National Centre for Writing, from May to August 2021, and explores the particular challenges of translating humour.

During the months of May to August 2021, I was one of the virtual translators in residence at the National Centre for Writing. During that residency, one of the key projects I worked on was translating Najwa Bin Shatwan’s short story collection, Catalogue of a Private Life. This collection won an English PEN Translates grant in 2019, and is published by Dedalus Books under their Africa imprint.

During the months of May to August 2021, I was one of the virtual translators in residence at the National Centre for Writing. During that residency, one of the key projects I worked on was translating Najwa Bin Shatwan’s short story collection, Catalogue of a Private Life. This collection won an English PEN Translates grant in 2019, and is published by Dedalus Books under their Africa imprint.

The blurb for the collection (which I wrote) reads:

A grandmother who takes on a thief trying to seduce her daughters. A guard who fantasises about killing his general while locked in battle with a non-existent enemy. A film script about Libya’s traffic problems improvised at a workshop. A woman’s letter from her old school, which is now a makeshift refugee camp. A cow straying into a field, breaking an age-old truce between warring factions. The eight stories of Catalogue of a Private Life feel like oft-recounted folktales, where the ordinary has been softly twisted several degrees. Najwa Bin Shatwan navigates the tensions between loyalty and betrayal, ambition and regret, and tenderness and cruelty to weave a portrait of family, war and nation against a stark backdrop of the completely absurd.

I’ve worked on Najwa’s short stories before, and have published a number of them on short-form outlets such as Words Without Borders, Arablit, The Offing and Adi Magazine. However, this was the first time I’d be working on an entire collection of hers to be published. This was in equal parts thrilling and daunting. Thrilling, because Najwa’s work is what makes me happy to be a translator today. Her prose is dark, witty, full of emotional tension, sprinkled with the fantastical – plainly put, a breath of fresh air on the Arabic literary scene. For all those exact reasons, it was daunting, too. As we all aim to do, I wanted to do the collection justice. I’d never had to deal with a work though where humour is the foundation. I’ve done some books where there are a couple of jokes here and there, some wordplay, but nothing like the minefield that is Catalogue of a Private Life.

So, where to start?

During the height of the pandemic, I came across Katrina Dodson’s challenging yet oh-so-marvellous talk at the Center for Fiction, where she outlines how to be more purposeful and intentional in your translation practice. If you haven’t seen it, you can watch it here. If you don’t have time to watch it, then just read this accompanying PDF.

Yes, it takes time to work through all the questions, but it’s definitely worth the effort. Katrina asks, ‘What are my blind spots and limitations in relation to this project and how might I remedy these?’ For this particular project, without a doubt and in flashing lights, mine were how to translate humour while making sure that I didn’t miss the layered allusions to Libyan culture and history. I could remedy the former through research and talking to other translators who have an established practice in dealing with humour – such Emma Ramadan and Jessica Cohen, who were so generous with their time and advice. The way I usually addressed the latter was by asking Najwa questions – sometimes a lot of questions! However, as the author was ill during this time, I also relied on one of her colleagues, Masoud Saleh Masoud, to read through my translations in case I was missing any embedded Libyan song lyrics or poetry, for example. We agreed that he would be paid for this work, and I’m extremely thankful to him for all his patience. I think it’s important to recognise when and where you need help as a translator. For me, every act of translation is a collaboration in some way or the other.

As a result of all the research I carried out on how to translate humour, I ran a three-week course at the British Library on ‘Translating Humour in Arabic Literature’. I’m delighted that it had such a good response, and hope to run it again in the future.

I had originally planned to do instalments of a translation diary while I was translating, à la Danny Hahn – HOW DOES HE DO IT?! – but it was nigh impossible. So, this is more a reflection after the fact, as the collection is going to the printers as I write. (Hooray!) I did keep notes while working though, recording what I could possibly touch upon here.

Decisions, decisions, decisions

As with all literary translation, you’re always faced with what to bring across and what to leave behind. But I find when translating humour, it’s that much more difficult to decide what to leave behind. Some helpful advice Jessica Cohen gave me was that you have to prioritise what needs to come across when translating humour. I’ve applied that uniformly, whether it be for a specific joke or an entire text.

From the very first line of the first story in the collection (The Burglar in White Socks), I’m faced with what to do with الله بقر (Baqrallah), one of the main characters. Najwa always plays around with her characters’ names, but not even all Arabic language readers pick up on it. In this case, بقر الله is a play on عبد الله (Abdallah). Abdallah means servant of Allah, a very popular name in Arab communities. But ‘baqr’ means cow, so the character’s name here means ‘cow of Allah’ or simply ‘Allah’s cow.’ When I asked Najwa to clarify her decision behind this name, she explained that it chimes with the character’s personality: someone who will follow Allah blindly, never questioning or thinking for himself, whilst also being remarkably, stubbornly set in his ways. There’s already a lot happening linguistically in this story with word play, etc., so I left dealing with this till I had finished translating the entire story. Sadly, I decided to just leave Baqrallah as it is, and to rather just amp up the character’s personality in certain scenes. I could have put in some sort of stealth gloss or clue, but as there’s a lot for the reader to unpack from the first sentence, I settled on just leaving this out. I probably will feel different about this next week and will be kicking myself because the perfect solution will have come to me by then.

I find when translating humour, it’s that much more difficult to decide what to leave behind

One of my favourite examples of the linguistic gymnastics I partook in during this collection is in the story Convention for the Protection of National Pestles. I already talk about the title (which is slightly different from the Arabic) and the difference between sexual innuendos in Libyan culture and English culture – which features at the end of the story – on the Translation as a Creative Act panel as part of Meet the World. So I won’t get into all of that here! The example I’m thinking about is the following sentence:

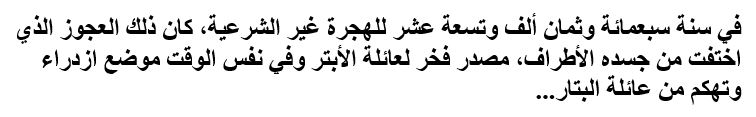

A literal translation of this is:

In 8719 of the illegal hijra/migration, that old man whose limbs had vanished from his body, was a source of pride for the Al-Abtar family, and at the same time an object of scorn and ridicule to the Al-Bittar family.

Okay that’s a bit messy, so let me tighten it up (cutting out any repetitive synonyms, for example, clarifying some concepts), so we can focus on the challenge at hand.

Take two:

In 8719 of the illegal migration, the old man whose limbs had been lopped off was a source of pride for the Al-Abtar family, but an object of ridicule to the Al-Bittar clan.

The underlined part is what we’re going to sink our teeth into now.

In 8719 of the illegal migration.

Najwa likes to play with time and space, sometimes merging the two together. Here, she is just playing with time. Usually, to signify the Islamic calendar in English you use AH, which in Latin is Anno Hegirae, meaning in the year of the journey (hijra) that the Prophet took from Mecca to Medina in 622 AD. Here, instead of saying just ‘in the year of the hijra’, Najwa throws in ‘illegal’. So she’s inventing a way to quantify and signal a time period. (Lucky me!) This is a lot of cultural knowledge that I’m assuming my reader possesses. But if you’re familiar with the Middle East or the Arabic-speaking world, a historian, or just well-read, you’ll know what AH means. Or even if you don’t, the fact that it appears after numbers probably signifying a year in history, you’ll know it’s akin to AD/CE or BC/BCE. So what am I trying to get across here to the reader? In the Arabic, this is something that isn’t laugh-out-loud funny, but it will make the reader crack a smile. And that’s what I’m going for.

I want to bring across that this is a time period marker, that Najwa is playing with words here, and that it adds a speculative element to this already fairy tale-esque story. I started thinking of adding the word ‘illegal’ in Latin to the already existing Anno Hegirae. But that’s a lot of Latin, and it might just completely go over the reader’s head. Illegal Hijri Year of 8719? Nope, too wordy. After a few other permutations, I got stuck and asked some colleagues for help. Lawrence Schimel came to the rescue here. I explained the situation to him and he promptly said, ‘Maybe use “in the Annulled Hegirae”? So it still looks/sounds like “Anno Hegirae?”’ I absolutely loved the idea of ‘Annulled Hegirae’, for the reasons he stated. He also suggested scrambling the ‘Hegirae’ to possibly ‘Anno Herigae’ or ‘Anno Hegari’, but again, I thought that was making this all more complex than necessary, and more than what it is in the Arabic. So I wrote the beginning of the sentence as:

In 8719 (Annulled Hegirae)

I submitted the manuscript and was pretty happy with what I had until it got to proofreading. Till that point, two editors hadn’t questioned it, but the proof-reader was completely lost and the head editor was in agreement with them. They asked me to provide a footnote. I pushed back and said I’d rather we cut the time reference altogether. Providing a footnote for a joke is akin to performing an autopsy on it – and who finds that funny? I then thought some more and suggested the following to provide the reader with more scaffolding:

In 8719 AH (Annulled Hegirae), or Anno Hegirae rather, the old man whose limbs …

After conferring with some of my Arabic-English translator colleagues (thanks Marcia, Nari and Nashwa!), I sent in my suggestion with the justification that nearly every reader will understand that two letters after a year signifies something like AD/Anno Domini, and if they miss that then they’ll still get the play on words of “Annulled” v. “Anno.”

I was relieved that the editors agreed to keep in this unique time reference while forgoing the footnote. SCORE!!

Providing a footnote for a joke is akin to performing an autopsy on it – and who finds that funny?

Now that we have done the first few words of this lengthy sentence, let’s move onto the next hurdle.

What we have so far:

In 8719 AH (Annulled Hegirae), or Anno Hegirae rather, the old man whose limbs had been lopped off was a source of pride for the Al-Abtar family, but an object of ridicule to the Al-Bittar clan.

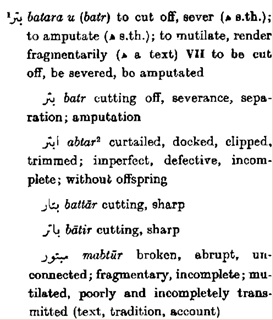

The context for this sentence is that, in the story, the main character gets his body parts cut off by two warring parties who are torturing him for information. Al-Abtar means the family that has had its limbs cut off. Al-Bittar means the family that did the severing. Both family names are from the same root in Arabic, b-t-r. A quick glance at the invaluable Hans Wehr illuminates us:

Spoiler alert: I’m not going to share what the final outcome was for this, because I’d like you to read it in the story itself and see what you think! As in … did you get the joke? But I will share here the considerations I had to take into account when thinking about how to bring this across into English.

What’s happening in the Arabic?

- Wordplay. You have two similar sounding words that have two different meanings. So I’m going to have to see if I can keep that relationship between those two words.

- The first family name has to call forth individuals who have had something cut off.

- The second family name has to signal the people who do such cutting.

- Cultural relevance. One of these is actually a real family name. So you could go with something like Al-Stubb and Al-Chopper (which is where I began), but it doesn’t fit within the Libyan cultural framework – that families would have names like that.

I’d love to hear how you would deal with this! Feel free to tweet me @sawadhussain.

Italian?

I surprisingly learnt some Italian words and Italian-inspired Libyan colloquial terms while translating this collection, because in Libyan Arabic there are flashes of Italian due to colonization in the first half of the twentieth century. A few times I was really stumped by certain words until I realised belatedly that they were in fact Italian or Italian-based. Over time, I got better at identifying these.

Final Thoughts

What I have discovered when translating humour is that sometimes you have to wildly depart from the text to find what you’re looking for. I definitely went too far sometimes and had to reel myself back in, but I found the courage to experiment in the first place after having chats with Jessica Cohen and Emma Ramadan.

I really love reading translation diaries, and I hope you have enjoyed these musings of mine. I have a newfound respect for people who keep them because one has to expose a part of their practice that they usually don’t – kind of like looking behind the curtain in Oz. I hope more translators write memoirs or diaries, as this is currently one of my favourite genres to read. To add my two cents to that body of work, I’ve written about my experiences as a translator of colour for the upcoming Decolonising Translation anthology to be published by Tilted Axis Press in July 2022. If you’d like to learn more about my practice, mosey on over there!

Sawad Hussain is an Arabic translator and litterateur who is passionate about bringing narratives from the African continent to wider audiences. Her translations have been recognised by English PEN, the Anglo-Omani Society, the Short Story Day Africa Prize, and the Palestine Book Awards, among others. She has lectured at IAIS at the University of Exeter, taught KS3 & KS4 Arabic in Johannesburg and Dubai, and run workshops introducing translation to students and adults under the auspices of Shadow Heroes, Africa Writes and Shubbak Festival. She holds an MA in Modern Arabic Literature from SOAS. Sawad was virtual writer in residence at National Centre for Writing from May to August 2021.

Sawad Hussain is an Arabic translator and litterateur who is passionate about bringing narratives from the African continent to wider audiences. Her translations have been recognised by English PEN, the Anglo-Omani Society, the Short Story Day Africa Prize, and the Palestine Book Awards, among others. She has lectured at IAIS at the University of Exeter, taught KS3 & KS4 Arabic in Johannesburg and Dubai, and run workshops introducing translation to students and adults under the auspices of Shadow Heroes, Africa Writes and Shubbak Festival. She holds an MA in Modern Arabic Literature from SOAS. Sawad was virtual writer in residence at National Centre for Writing from May to August 2021.

Read: Sawad Hussain’s five tips for pitching to publishers →

You may also like...

Five tips for pitching to publishers

Visible Communities virtual writer in residence Sawad Hussain shares her advice.

15th October 2021

NCW Emerging Translator Mentorships 2021-2022

The National Centre for Writing is delighted to announce the mentees selected for the 2021-22 Literary Translator Mentorships Programme

4th October 2021

Five great tips for getting started as a literary translator

Thinking about a career in literary translation? International Booker Prize-longlisted translator Sophie Hughes offers some early advice

4th May 2020