Editor and translator Nadiyah Abdullatif has written this commission reflecting on her experience translating Mauritian literature with National Centre for Writing during her Visible Communities virtual residency.

Nadiyah reflects on her formative experiences with Mauritian Creole, or Kreol, and the commonplace negative attitudes to using Kreol, even amongst some Mauritians. She recounts how the NCW residencies have opened up opportunities for her to afford to translate, and the need for more of them, as ‘[s]uch initiatives are vital for making literary translation accessible and ensuring the diversity of both translated content and translators.’

Our Visible Communities programme aims to diversify access routes to literary translation, strengthen links between the literary translation community and diaspora communities in the UK and contribute to the debate around decolonising literary translation. You can read more about this programme here, or learn about our residencies here.

Find Nadiyah Abdullatif’s thoughts below.

Vanilla Sorbet:

My experience of translating Mauritian literature with the National Centre for Writing

Nadiyah Abdullatif

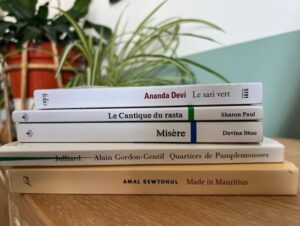

Some of the books I read and worked on during my residency. Not pictured here is Quand montagne prend difé… (1977), the first novel published in Mauritian Creole, which is available to read at the British Library.

Introduction

Over the course of my two residencies with the National Centre for Writing, I embarked on a broad reading of Mauritian literature that had not yet been translated into English and translated extracts from a variety of works with the aim of pitching them to magazines and journals for publication. I also explored the possibilities for working on full-length translations. My aim was to help make Mauritian literature become more accessible to the wider world, as well as to anglophone Mauritians and members of the diaspora, while nurturing my own connection with Mauritius—the country of my birth—from afar.

I selected novels that explored Mauritius’s colonial history, its diverse ethnic and religious groups and inter-communal relations within the country, texts that used Mauritian Creole, and texts that were written by authors who had not previously been translated into English. Some of the works I explored were set in the independence period, the period leading up to it or shortly following it, an interesting time when there was a surge of communalism and identity politics in the country. Others were set well before independence, and explored socio-economic inequalities and societal taboos such as interracial relationships. Themes of societal inequality and questions of identity, belonging and social cohesion amid diversity were a common thread linking all the works I studied. I selected these to fit with the aims of the Visible Communities programme: not only were the protagonists of the stories often members of visible minorities in Mauritius, but by translating their stories and amplifying the authors’ voices, I would be helping to bring more international visibility to the Mauritian community as a whole. I also felt that these texts contributed to the debate on decolonising literary translation and expanded the range of literature published in translation. A key intention of mine was to showcase and promote Mauritian authors, to get Mauritian stories heard, and to have our languages, history and culture represented and acknowledged.

Mauritian Creole: A background—or more specifically, my background

A particular interest of mine was finding texts containing Mauritian Creole, or Kreol, and I spent a significant amount of time seeking the rights to translate the first novel written and published in Mauritian Creole (which sadly didn’t work out in the end). It was an intimidating prospect for a number of reasons. Like most Mauritians, I have never formally studied the language. I find very few opportunities to read or write in it (beyond the occasional newspaper article or WhatsApp message), and I speak it only in very specific situations despite feeling very connected to the language. While this is partly due to me living outside Mauritius, it is also likely due to Mauritian Creole having a long history of stigmatisation, leading to its exclusion in certain contexts. The language only obtained a place in the Mauritian education system in recent years, and officially standardised writing systems for it only emerged following the establishment of the Akademi Kreol Morisien by the Mauritian Government in 2010.

I feel that it’s important to mention that growing up in England, I wasn’t raised to speak Mauritian Creole. I was supposed to grow up bilingual—speaking English and French—but one parent didn’t keep up their side of the bargain. Kreol and French are languages I picked up over years of spending school holidays in Mauritius and later began actively cultivating as my love of languages developed. My opportunities to practise Kreol far outweighed those to practise French, given most of my extended family was primarily Kreol-speaking (they speak English and French too, but many seem to feel most at home with Kreol), and so, in the end, I grew up with the wrong language pair. As a child, it was stressed to me that my first language was English, with the implication that this was a sort of badge of honour. I didn’t fully understand the distinction between Kreol and French and was advised to explain to my friends, who had never heard of Creole, that the language my family spoke was “broken French”. I remember thinking that was a funny name for a language, and it gave me the false impression that I’d be able to communicate smoothly with any speaker of French.

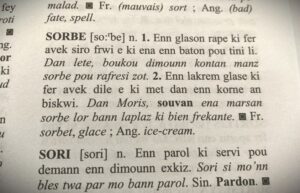

This misunderstanding led to some odd experiences. The earliest I remember was at an ice cream counter at a restaurant in Mauritius, perhaps aged six or seven, when I asked for some “sorbe vani”. The man at the counter did a double take, repeating my words back to me incredulously, as if what I was saying was the stupidest thing in the world. Sorbe, in Kreol, is a generic term for a soft, frozen dessert regardless of its dairy content. As with French and Kreol, the distinction between ice cream and sorbet was something I simply didn’t dwell on. So when the French-speaking man at the ice cream counter said “ça n’existe pas”, I was quite surprised and confused, given there was some ice cream in front of me that I strongly suspected was vanilla-flavoured. I had the sense that the man at the counter knew exactly what I meant, and after a prolonged stalemate in which I looked blankly at him, he eventually scooped up the vanilla ice cream all the while emphatically saying “glace vanille”, only handing me this glace once I repeated the words after him. I still remember that first suspicious taste, wondering if he had got my order right after all.

Image from the first monolingual Mauritian Creole dictionary, the Diksioner Morisien by Arnaud Carpooran.

Nowadays, when I go back to Mauritius, I feel much more equipped to handle situations like these and switch between languages more easily. This was a necessary adaptation: the next generation of my extended family seem to have mostly switched towards using French as their main language, whereas the elders still primarily speak in Kreol, and English is the default language of all WhatsApp groups. It’s an odd system and seems to be reflected in other parts of Mauritian society: on the radio, adverts for instant noodles are in Kreol, those for accounting qualifications are in English, and those for spas and beauty products are in French. I feel like it says a lot about the connotations associated with each language. There seems to be an enduring hierarchy of language use, where some languages are seen as superior to others and become more economically important than others.

The stigma associated with Kreol that I mentioned earlier hasn’t fully disappeared. In recent years, I have been told—by a Mauritian— to “stop jabbering on in that uncivilised language” and have met Mauritians who will only communicate in English or French. When I told relatives that I was reading a novel written in Kreol and considering translating it, some joked that I must have a lot of patience to attempt to read anything of that length in Kreol. I’ve also witnessed unpleasant reactions from people of other French-speaking backgrounds, who mocked my Mauritian heritage, sniggered when I mentioned Kreol, and objected to me working with and promoting the French language and francophone culture. Alongside all this, to this day I still get teased for my English accent in Kreol.

All of these odd experiences with language seep into how I view myself as a translator, as a linguist and as a Mauritian. There are times when I feel I mustn’t speak a word in French unless I’m sure to speak it perfectly, for fear of being caught out making a mistake and this being attributed to my heritage, to my knowledge of a language that some still see as non-standard French. Equally, I feel a sense of loss in relation to Kreol. It’s a language I always find myself stumbling in. It has been my only means of communication with some family members, and so along with my life-long lack of fluency I also mourn the lost potential for connection. Knowing how imperfectly I speak it makes me feel like an imperfect Mauritian, an impostor—and this is only reinforced by my limited experience of living in Mauritius.

At times, this has left me questioning whether I am qualified to work with these languages or with Mauritian literature at all. But when I confided in a relative about these thoughts and suggested that people growing up in Mauritius, who have much more even exposure to all three of its main languages, might be better placed to work as translators, she explained that she doesn’t feel truly fluent or that she can call herself a “native speaker” in any one of her three languages. I was saddened by this (I hesitate and second-guess myself in all of my languages, but I’m glad I feel quite comfortably at home in one), and over time, I saw many other examples of her experience. The author who is “not that francophone” these days and prefers to exchange e-mails in English. The multilingual businessman whose website needs proofreading in English and French. The kids who’ll reply in French when spoken to in Kreol or English. Even at a recent birthday party during the Wordle craze, the Mauritian version of the game, Zwemo, using the recently standardised Kreol spellings demonstrated how difficult it is for the average Mauritian to think of a five letter word in Kreol, let alone try to spell it. I now try to accept the impostor syndrome as part of a distinctly Mauritian experience, and I find that the best way to soothe it is to continue reading and working on Mauritian texts, especially ones that touch on language use, migration, rootlessness and belonging. In doing so, I have come to realise that the discussion and use of Mauritian Creole in literature may be similarly cathartic for the authors themselves as well as for other Mauritian readers, and that I may not be alone in feeling a sense of loss in relation to Kreol.

Ils m’ont mis á l’école pour apprendre l’anglais et le français

Ma langue maternelle que je dois oublier

Assis sur les bancs devant mes maîtres

Je dois oublier la langue qui m’a bercé

[To learn English and French they sent me to school.

Forgetting my first tongue was the new rule.

My teachers, my masters preferred

For me to forget the first songs I ever heard.]

My own loose translation of an extract from Le Cantique du rasta (p.39) by Sharon Paul, a novel inspired by the life of Mauritian singer Kaya.

Emerging as a literary translator and the National Centre for Writing’s support

When I heard that I had been offered a place on the National Centre for Writing’s Visible Communities residency programme, I was elated. I hadn’t been working in literary translation long, but my early experience of it had been tough, and this opportunity was a flash of hope amid rejections and defeats snatched from the jaws of victory. I had participated in a few “beauty contests”, the often unpaid and time-consuming work of preparing translation samples in the hope of securing contracts. In some cases, I had come very close to being selected. In others, I had been told that I wouldn’t get this contract, but I’d be contacted about another one very shortly. In all of these cases, I didn’t really get anywhere. In the meantime, I was having a hard time contacting the authors and publishers of the texts I hoped to work on, getting little or no response from the publishers of the original texts (over the course of the residency, I discovered that this process alone, simply to confirm that translation rights are available for a text, can take months). I was also only able to spend a miniscule percentage of my time on literary translation, with commercial translation and editing being my main source of income, and my literary work being voluntary or honorarium-based.

The National Centre for Writing’s support was a gamechanger. At the time of applying for the residencies, I had only one publication to my name: a co-translated extract of a graphic novel. After completing the residencies, I had three more confirmed publications in literary magazines (see one of them here) and two book-length offers from publishers. While I will need to return to doing a higher proportion of commercial work following the residencies, I know I owe thanks to their supportive, cocooning environment for this butterfly-from-chrysalis emergence on the literary translation scene. I now have greater access to paid literary opportunities than before, which means that the proportion of time I can spend on literary work will be higher than before the residencies. Consequently, I cannot stress enough how valuable the residencies offered by the National Centre for Writing are as early-career support, and how helpful they have been for me to be able to devote time to literary translation, to build a network within this field and to do so with some financial stability. Through the residencies I had the support and feedback of other translators on the programme and that of my mentor, Meena Kandasamy (in addition to my long-term mentorship with another NCW mentor, Sawad Hussain), access to networking events, and most importantly, guaranteed time and space to work on literary projects.

While I thoroughly enjoyed my residency experiences and especially the project I’ve been working on, spending more time on literary translation opened my eyes to some of the issues in this industry, such as the extent of underpaid and unpaid work as well as precarious working conditions. Through pitching and submitting, I was often surprised at the fees that were offered for work, which were at times far below the Society of Authors observed rates. While there are many reasons for this, the implication for me at least is that I’ll need to keep applying for external funding if I want to continue doing a significant amount of literary work. If we truly hope to decolonise translation, in addition to thinking hard about the languages, cultures and stories we translate, we also need to think about how the levels of pay available create an unlevel playing field for people entering the profession. I don’t have the answer to how we can change this, but can tell you that funded residencies like these are part of it. Such initiatives are vital for making literary translation accessible and ensuring the diversity of both translated content and translators.

Some of the texts I worked on and where they took me

- Made in Mauritius (2012) by Amal Sewtohul. This book, for which the author was awarded the Prix des cinq continents de la Francophonie in 2013, transported me to the Port Louis of my parents’ time, the city they both grew up in and in which I spent most of my childhood holidays. Dedicated to the independence generation, it tells the story of Laval, the son of Chinese immigrants to Mauritius, who lives in a shipping container with his parents in Port Louis, the Mauritian capital. Laval’s gloomy, solitary childhood changes when he meets his friend Feisal, and they explore the island together in the lead up to independence, a time when tensions between communities are high. I managed to actually travel to Mauritius while reading this, wandering through key locations such as Port Louis’s Chinatown and Belle Mare. My translated extract was published by Wasafiri.

- Quand montagne prend difé (1977) by Renée Asgarally. This was the first novel written and published in Mauritian Creole. It tells a tragic love story between two members of different religious and ethnic communities, addressing a long-held taboo which the author would have had first-hand experience of, being from a Christian background and having married a man from a Muslim background. As the work was no longer in print, I travelled to the British Library to read this novel and Renée’s other works, which included short stories and children’s stories. Although I couldn’t secure the rights to publish a translation, I enjoyed reading and researching this novel. I even found out that my uncle used to perform in the Kreol-language plays written by Renée’s husband, Azize Asgarally!

- Le Cantique du rasta (2021) by Sharon Paul. This début novel and winner of the Prix Indianocéanie 2021 opens with verses in Kreol about the journey of slaves sent by ship and in chains to Mauritius and gives an insight into the significance of the Mauritian musician Kaya. Kaya was the inspiration for the novel’s main character, Nas, whose song lyrics in French and Kreol appear throughout.

- Misère (2019) by Davina Ittoo. Another début novel and winner of the Prix Indianocéanie 2019, this novel touches on the journey of indentured labourers from India to Mauritius and the intercommunal violence of the 1960s, focusing in particular on tensions between Muslim and Hindu communities in rural parts of southern Mauritius. While reading this, I visited Aapravasi Ghat, the immigration depot where indentured labourers from India, East Africa, China and Southeast Asia were processed before being sent to work on sugar plantations. My translated extract was longlisted for the 2021-2022 John Dryden Translation Competition.

I am still looking for a home for some of these texts, so if you’re an editor or publisher interested in any of the pieces that feature in this article, please contact me via Twitter (@Nadiyah_FA).

Nadiyah Abdullatif is a Mauritius-born, Scotland-based editor and translator working from Arabic, French and Spanish into English. Her work has appeared in Wasafiri, ArabLit Quarterly and The Markaz Review. She has been a translator-in-residence with the National Centre for Writing, has worked as a copy editor for Asymptote, and was recently longlisted for the 2021–2022 John Dryden Translation Competition.

Nadiyah Abdullatif is a Mauritius-born, Scotland-based editor and translator working from Arabic, French and Spanish into English. Her work has appeared in Wasafiri, ArabLit Quarterly and The Markaz Review. She has been a translator-in-residence with the National Centre for Writing, has worked as a copy editor for Asymptote, and was recently longlisted for the 2021–2022 John Dryden Translation Competition.

We would like to thank Arts Council England for supporting the Visible Communities programme, the British Centre for Literary Translation for collaboration on the BCLT Summer School, the Stephen Spender Trust for Multilingual Creators, the Francis W Reckitt Arts Trust for supporting residencies at Dragon Hall, and the Jan Michalski Foundation for their support for the Tilted Axis Press anthology and our virtual residencies.

You may also like...

Decolonising translation: a report by Coco Mbassi

A Visible Communities commission by our virtual resident Coco Mbassi

21st December 2022

Five tips for pitching to publishers

Visible Communities virtual writer in residence Sawad Hussain shares her advice.

15th October 2021

Emerging Translator Mentorships: Ten Years On

Vineet Lal reflects on his career over the past decade and shares his advice for emerging translators

31st March 2021