In this episode of The Writing Life, our Chief Executive Chris Gribble speaks with writer, poet and educator Raymond Antrobus in an interview which was recorded ahead of his performance at the City of Literature weekend 2023. City of Literature takes place in May each year and is a National Centre for Writing and Norfolk & Norwich Festival partnership, programmed by National Centre for Writing.

Raymond was born in London, Hackney to an English mother and Jamaican father. He is the author of Shapes & Disfigurements (Burning Eye, 2012), To Sweeten Bitter (Out-Spoken Press, 2017), The Perseverance (Penned In The Margins / Tin House, 2018) and All The Names Given (Picador / Tin House, 2021). In 2019 he became the first ever poet to be awarded the Rathbone Folio Prize for best work of literature in any genre.

Raymond chats to Chris about his development and life as a poet and educator: from finding a community in the London spoken word scene to winning the Folio Prize for The Perseverance through to his most recent collection All The Names Given. He discusses the challenges and joys of working in the poetry ‘business’ as well as the poetry community.

Edited by Omni Mix

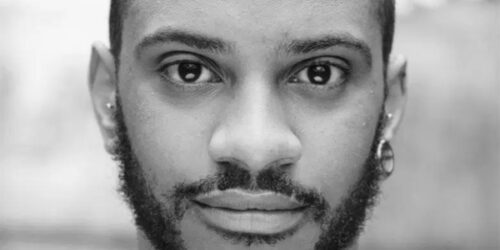

Image © Caleb Azumah Nelson

Transcript

Steph McKenna

Welcome to The Writing Life, the podcast for anyone who writes. I’m Steph McKenna from The National Centre For Writing, here at Dragon Hall in Norwich UNESCO City of Literature.

It’s July 2023 and in this episode I’m here to bring you the first interview from our fantastic festival of words and ideas, the City of Literature weekend. City of Literature takes place in May each year and is a National Centre for Writing and Norfolk & Norwich Festival partnership, programmed by National Centre for Writing.

Today’s conversation takes place between writer, poet, and educator Raymond Antrobus and NCW chief executive Chris Gribble, just before Raymond took to the stage to perform at our event celebrating 100 issues of Norwich-based poetry magazine The Rialto.

Raymond Antrobus was born in London, Hackney to an English mother and Jamaican father. He is the author of Shapes & Disfigurements, To Sweeten Bitter, The Perseverance and All The Names Given. He has been awarded numerous accolades including being the first ever poet to be awarded the Rathbone Folio Prize for best work of literature in any genre.

Raymond chats to Chris about his development and life as a poet and educator: from finding a community in the London spoken word scene to winning the Folio Prize for The Perseverance through to his most recent collection All The Names Given. He discusses the challenges and joys of working in the poetry ‘business’ as well as the poetry community.

So now, I’m delighted to hand over to Chris in conversation with Raymond Antrobus.

(Beginning of Interview)

Chris Gribble 1:34

Well, welcome this afternoon – Raymond Antrobus you’re our guest on The Writing Life Podcast. And in this beautiful day in May. Welcome to Norwich.

Raymond Antrobus 1:42

Thank you. Thank you for having me, Chris. Good to be here.

Chris Gribble 1:45

And so, we’re recording this in Dragon Hall on the afternoon of the first, middle afternoon, of our City of Literature Festival. This evening’s event that we’re going to be celebrating is to mark the 100th edition of Rialto Poetry Magazine. And you’re going to be reading as part of that—

Raymond Antrobus 1:65

Yes.

Chris Gribble 1:66

So, tell us a little bit about your history with Rialto?

Raymond Antrobus 2:06

So… this is a little bit of almost, like, a religion story in a way. Because the way that I came across Rialto… So, in 2013, I was doing an MA at Goldsmiths University. And my supervisor for my dissertation was the poet, Jack Underwood. And what I had to do for the last kind of section of this dissertation was write a selection of poems, which kind of linked to some of my own projects. My MA wasn’t even in literature, it’s actually more in learning and teaching and what that can look like in different kinds of settings.

But actually, it was more focused on something called emotional literacy. And so yeah, you know, I was almost spent three years going into schools, doing case studies, teaching creative writing, poetry, and performance, all these kinds of things… And something that kind of happened around that time, my dad got really sick, and he was dying…

So, I had all this stuff happening. And I started writing these poems, and Jack saw them and was like: “Hey, have you ever submitted poems to journalists before?” And I said: “No. Why would I do that?” That wasn’t really part of my vision, I think, in my career as a writer at that point. I was more interested in being heard, than I was in being read. If that makes sense–?

Chris Gribble 1:66

Yeah.

Raymond Antrobus 2:06

Even though I had countless literary influences, and inspirations. My mother’s very literary. But yeah, for my own work, that’s why you know, I was thinking along the lines of almost being listened to the way that you might hear a dub poet, like Linton Kwesi Johnson, or Jean Binta Breeze. And they’re the kind of poets that my dad used to play me on cassette tapes.

One of them right here on my arm, is a tattoo of a tape on my arm.

And so, anyway, sorry, that was a bit of a long way to say that Jack took a selection of my poems, put them in an envelope. Like, he did the whole thing. And I just watched him.

And then he’s like: “Right, we’re gonna send this to The Rialto, we’re sending this to The Poetry Review, sending this to Poetry London…”

And so, he like, held my hand through that process. And I’m kind of I’m kind of forever grateful for him. Because it wasn’t the kind of story of like, oh they got sent off and they got accepted – because they didn’t. They got rejected.

But it was the rejection, actually, from The Rialto which was the most encouraging. And so a second time I decided to submit to The Rialto – probably about a year after that. I managed to get a couple of poems in… and I just remember feeling, just kind of such a mix of things, I suppose that kind of, you know – surprise, elation, in some ways. And then also interested in knowing the meaning of Rialto. The bridge. So, it really was a kind of bridge towards, I suppose – to a slightly more literary path for myself. Because I think maybe one of the reasons I didn’t bother submitting or needing that kid of push across the bridge, that particular bridge… I just kind of assumed that there wouldn’t be space for me in the literary world, from what I understood of it, and from what I saw of it. I think I very much came from a kind of open mic background. But, like, growing up my parents would take me to see poets like Adrian Mitchell, and Roger McGough – Brian Patten. You know those Liverpool poets.

As well as Benjamin Zephaniah, Lemn Sissay… So, poetry and prose – they’re always there. So, I never felt like it was something I couldn’t do. But from what I’ve seen on the kind of more literary side of things, I felt like I didn’t yet have a model or an idea of the space I could occupy. So yeah, The Rialto – It’s quite literally, the beginning of a journey – a step across that bridge. Sorry, that was quite a long way to answer that.

Chris Gribble 7:18

No, it’s wonderful. It opens up lots of questions that I’m definitely going to come back to. So, it’s 2015–?

Raymond Antrobus 7:22

2015, yeah—

Chris Gribble 7:22

Since you were in the winter Rialto–?

Raymond Antrobus 7:23

Yeah. That’s right, yeah.

Chris Gribble 7:25

I’ll have to get researching. Because we have the 100th celebration. Michael’s a fantastic figure in our kind of – shared literary heritage, as well as the country. Can I ask, I mean, we work with a lot of early career writers here. And one of the big struggles that people face is kind of literally crossing that bridge into calling themselves a writer, or kind of allowing themselves to classify themselves as a writer. What did publication and acceptance into another part of the literary world do to you as a writer?

Raymond Antrobus 8:04

I think it allowed me to see myself in print. And print has a scary kind of permanence to it. Because at that point, the relationship with my work – my poetry specifically – was that I would learn poems, and I would perform them in public – and I had kind of a number in my head that I had to perform a poem in public at least five to ten times before I kind of know what it is and what it’s doing… And before I can kind of really, you know, establish it, and feel it but this was a very kind of personal, internal kind of relationship, and I was trying to it make coherent for and with myself. So that I can connect it and deliver it to an audience.

So, publishing it’s a little bit… it feels a bit different. This feels a bit scarier, actually, because you’re literally saying, Here’s texts, and here’s a shape of a text. And I’m trusting you, reader – to engage. But also, you know, I’m not saying that to be didactic and be like: “This is what it means!” But yeah, I’m just hoping that when a reader comes to work that they are… this is gonna sound strange, but I really hope for generous readers. The interesting thing about poetry in particular, is that its subjectivity can be it can be an amazing (and a brutal, cruel) thing. Coming up in the way to… just the way I suppose that I did, to language – I spent five years in a deaf school. Before that I was in special education or needs units. I’ve had years and years of different kinds of therapies to help me, you know, develop language – literally.

I think a big part of taking on poetry was realising that poetry was seen as this kind of ultimate kind of language – an ultimate kind of, you know, challenge – in a way it’s like: if you can do this, we can, you know… You get an opportunity to show something of yourself that I started to realise that people didn’t expect from me. So in a way, it was a way to prove people wrong, I suppose, in some ways. But then in another way, that’s not the entire kind of picture of that. Because in another way I think I really do have a natural inclination, passion, instinct, for language and for sound. And so, I’ve just kind of tapped into that and allowed my passion, in a way, to guide me and I’ve had to trust that and so… yeah, I mean, there’s so many things that played… so many threads in so many places, that I can go with that.

Chris Gribble 11:37

You have to kind of step back from the control that you have as a performer.

Raymond Antrobus 11:39

Yeah.

Chris Gribble 11:41

And ask, or hope, for a lot more trust in some ways.

Raymond Antrobus 11:46

Exactly. Yeah, exactly. The page was… I guess from when I first started getting published, I realised that the page was scarier than the voice, and the body. Which was my instrument. Which was my, in a way – my place of safety. But then I became interested in challenges and became interested in the kind of conversation or the kind of… aesthetic space platform that the written poem, the printed poem, the text poem takes up. Which is… which isn’t a binary actually, I don’t see the page and stage as kind of opposite things.

So, when people talk about that, that kind of page/stage thing. I’m always like, there’s clearly something missing in your kind of literary taste, knowledge, understanding… If you know, because if we were in this place where people are like giving someone like say… Bob Dylan a Prize for Literature, then that shows that the culture is understanding a relationship between say the spoken the sung, the said word, and literature, right. But as a kind of wilfulness there, because I find that, you know, things in their kind of literary space or academic space… I realised as well coming out of academia. I realised that the way that people were talking about say “craft” became a kind of code speak for a kind of intentional exclusion – it’s a way, often, for people to draw a line in the sand and say: “This is the language in which there’s / good—

Chris Gribble 13:39

Good—

Raymond Antrobus 13:39

There’s a good value system—

Chris Gribble 13:39

Good, bad.

Raymond Antrobus 13:41

Right. Exactly.

Chris Gribble 13:43

Professional, amateur. High, low.

Raymond Antrobus 13:45

All of that. And the thing is – that kind of field of tension felt very similar to me being in school, and going to these kinds of different special educational units and seeing how people respond to me, and my peers and how people respond to… say when I was learning sign language, and that became this thing, of like: “You’re not signing correctly.” So, there’s all of these kinds of interesting things and I realised: “oh wow, language is so powerful” and people are so desperate to kind of, you know, control the power of language. That, you know, again, I don’t think choosing to dedicate my life to poetry and literature and Language in this way. I don’t think it’s an accident. You know, it’s a way in a way to kind of carry on, you know, developing my language and my sensibilities of speech and the written word and the spoken word and all these things which I’m still kind of very invigorated by.

Chris Gribble 15:01

I wonder sometimes if the desire to control language is more about people’s desire to control their anxiety, about belonging and not belonging.

Raymond Antrobus 15:05

Completely.

Chris Gribble 15:08

To simply having that “us, them.” That kind of feeling that can be… I started in the… I suppose I started in the page poetry world. I worked at Carcanet Press back from 1998. And then I moved into Manchester Poetry Festival where we had slams on a really vibrant kind of spoken word scene in Manchester. People like Kei Miller came through that. Early days at the Manchester Metropolitan University – Thick Richard and this whole brilliant sort of canopy of people. And I found it a real struggle – that page/stage discussion didn’t seem… it didn’t seem to be a very fruitful and most often it wasn’t about poetry at all. When I was reading, because you briefly mentioned your MA. You did your MA in spoken word education at Goldsmiths, one of the very first people in the world, I think, to go through that programme. You made a comment in the London magazine about how you realise that, that London spoken word scene was more of a community than a genre. Can you tell us a little bit about those days in that scene and how it’s kind of oriented you in the world?

Raymond Antrobus 16:23

Yeah, I suppose like – writing is hard, creating his hard, and it is very easy for someone like me to think and talk myself out of writing a poem or pursuing you know, pursuing a creative life or life in the arts, because everything in a culture you know, capitalist culture… It goes against that, because there’s no kind of definite value in… what fifty pounds, maybe, maybe… You’d be lucky to get fifty pounds to publish one poem. You know, like the money is… I mean no one is making a living right off that. So, you have to be motivated. By almost, I don’t know, instinctive… I’m hesitating on using words like “madness.” Okay. But it really was a kind of like, you know, articulate–

Chris Gribble 17:38

Other sources of nourishment.

Raymond Antrobus 17:41

Right. Yeah, exactly. That I just needed. And so, what I found in the early years of like, open mics, it wasn’t slam, it was open mics and then it was slam. And then after that, it was just kind of, you know, trying to make like a twenty minute woven set of poetry where everything kind of flows, almost like the way that – I know a lot people who are in stand up and the way they talk about weaving together bits towards the show, like, you know, spoken word in that when I was doing that, a similar thing I was trying to go in for like a cohesive like five minutes, ten minutes, then fifteen minutes, twenty minutes. And then, like you’ve got a set, and then you can like tour with that. You know, put yourself out there. So, there were different nights like Hammer and Tong – A couple of nights that don’t exist anymore, a couple of nights that I don’t even want to mention. But as you know, there’s a whole circuit and what I learned quite quickly when I started the circuit, was I was just UK, but there was like Europe – because I was also going around Germany, Italy, and Switzerland. I did a couple of gigs in France. There’s a whole kind of other world, almost. It was really interesting discovering that because I’d go to these other countries, other cultures, and I would find almost like doppelganger versions of Paris and London. See, like, the French version of this poet – down in, like, Peckham or something. Wow. That was almost a kind of sign for me. I was connected. I was in a network. And you know, if it fed me and encouraged me in a way that I think if my vision was only to sit at a desk, right here with paper and pen and just write and then just throw it out there and just pay someone like that one. I don’t know if that would have… if I ever had the stamina for that. So, I think in the early years I just — Yeah, I just got a lot of… I guess – nourishment and encouragement and support. I felt that… in a way because, I think, everyone… or a lot of people seem to understand that you’re not in this for the money, that there really is something else at play with, with you, and some… some of that is quite eccentric.

Chris Gribble 20:30

And that’s a shortcut to trust though, isn’t it?

Raymond Antrobus 20:31

Exactly.

Chris Gribble 20:35

You know that someone’s not riding this for financial gain.

Raymond Antrobus 20:39

So, it’s – again like, you know, talking to people who are, like, in the comedy world, they say it’s a very different, it’s that kind of thing…. So, yeah, I forgot what the question was. Sorry.

Chris Gribble 20:52

I suppose I was kind of interested in kind of what – how you found yourself oriented in that world. By whom. And were there other individuals? Kind of, who really – sort of helped you locate yourself. I’m particularly interested in the notion of mentors and mentoring. Because there has been a real resurgence in the last ten years, around the structure of mentoring. It did happen organically in a lot of ways as well. Did you benefit from mentoring in that life, in that spoken word scene?

Raymond Antrobus 21:23

Oh, yeah. So, there were there were some very concrete mentors, which I was so privileged to have, which I don’t think I would have gotten to that kind of next stage without. So, Malika Booker was my first poetry mentor. And now that happened… I was at an open mic. There was a woman who worked for an organisation called Apples and Snakes. She came up to me after I’d read, like 10 minutes of some poems… And she said: “You know, you’re really interesting.” And I’m like, you know, a nineteen-year-old… You know, just writing these poems and just very excited. So, she recognised someone who was passionate. But also recognised someone that needed some guidance. So, she said: “You know, I’ve got I’ve got a poet I think you should meet up with and speak with. She’s called Malika.” So, what happened – was, Apples and Snakes somehow… And this is… I don’t even know if this would still happen, but they put up some money to pay Malika Booker to mentor me for six sessions. They ended up in over six months. And we met… we would meet at the poetry library in the South Bank in London. And I’ll never forget this; Malika sat me down at this table and she said: “Okay, let me see your notebook.” And I showed her my notebook. She looked through it, like: “Okay, cool. Okay, cool. Now, before I talk about your writing, let’s talk about your reading. What are you reading?” And I was kind of like, well… I do a lot more… You know, I was I was talking a lot more about, I guess, prose writers at that point. And, and there were some poets I was reading, but I suppose not in a way that I knew how to talk about them – or applying their work to mine. Malika made a point of, like: “Okay, well, let’s get you reading…” In a way like reading like a poet – basically, reading like a writer – So, that your reading can fuel your writing. So, she sent me to the bookshelf, she did, and said: ‘Okay, now pull three random books off the shelf…” And I forget two of them that I pulled off. But the one I remember…Oh no, no – two of the books I pulled off, I remember – Blizzard of One, by Mark Strand… and a Charles Simic book… Title escapes me now.

But I opened up it up – the Mark Strand book, and there’s this poem called The Mirror. And it’s a poem, a narrative poem, very slender shaped poem on the page, and it tells the story of a man showing up at a party – And he’s holding a drink and he’s got this line about how the setting sun – yellow is the drink, and it looks, you know, so he’s looking at the drink – looking at all these reflections in the glass, and then he looks up and sees a mirror on the ceiling… And he notices a woman on the other side of the room, but he can only see her in the mirror… And the whole poem is just him noticing this woman on the other side. And wondering: “What is she doing? What is she doing?!” You know, that’s literally the question of the poem. What is she doing? You know… Is she waiting for someone? And then he imagines this life where he could be this person and… You know, it did that Dickinson thing of like, it spun my brain, because it was just this deceptively simple thing – of simple straight language, but more importantly, image and idea, there’s all kinds of, you know, opportunities to just go off you know… reflection, narcissism, you know. And, yeah, I remember I read that that poem to Malika and she was like: “Great, what do you like about it?” That’s all. That’s all it was, just asking me to respond. She just wanted to see me respond to literature. When she saw me respond, she was like: “You’re a poet. You’re a poet.” And she said that before she read the work. And so that was interesting. You asked me earlier about, you know, what’s happened – if I call myself a writer, or I call myself a poet… And I think I really internalised the idea that I couldn’t call myself a poet, or a writer, until someone else did. So, Malika, in my memory anyway – was the first person to say that. You know, another poet saying: “You’re a poet” and recognising themselves in you.

Chris Gribble 26:48

Yes, we do quite a bit of work with early career writers and literary translators at The National Centre for Writing, and work hard to give people opportunities, introductions, skills. But eighty percent of the work is giving them a group of people – within which they can… they are told they are, and that they can call themselves writers. That’s really powerful. You’ve done a lot of learning in lots of different contexts. You talked about being in different schools, educational needs, deaf school, mainstream schools, academia – What is it with a mentoring, what’s the learning moment that’s particularly different or powerful, do you think?

Raymond Antrobus 27:23

I think the mentoring… Well, it’s two things… I think it’s the kind of… In a weird way, it’s almost like a… This is this might be a little bit revealing, but like, because obviously your mentor is, you know – they’re older… and there’s a kind of elder respect, but also a kind of, you know, family slash, like, parents’ thing. Kind of why I realised this later on in my life actually looking – looking back at this time, but I think there was a part of me that was looking for the kind of parents I wish I had. And it was quite interesting that I ended up for some time being sustained by these mentor fingers. Who kind of were, almost stand-ins for my parents. Like it’s interesting, like, you know, it’s quite gendered as well. In terms of my mentoring. So, you know… and the women that have been mentoring me have quite a motherliness to them, and to their to their work. I don’t know if I want to say their names… but, you know, and same with the men. And I think that it was important for me though, to realise that and recognise that, and kind of state that – and take a step back and really… because they’re not my parents, you know, Malika is not my mother – she’s not my sister, my auntie – these poets are not my dad. So, when I… when I kind of figured that out for myself, it actually helped me – Helped me, maybe even, like, to be able to focus on the work a bit more… than, you know, my own kind of emotional needs. Yeah, it’s interesting because as well, discovering… I’m trying to figure out how to how to say this… I’ve never really articulated this… it has been a feeling for a while, but like… How I found in poetry and literature…. Yeah, it’s my own kind of way to curate my family, my friends – the conversations I want to have…

Chris Gribble 3:09

Your logical versus your biological family.

Raymond Antrobus 3:14

Right. I relate to that. Those ideas you know… So, like… in a strange way, like I kind of… I really needed that. I really did. Just a thing that kind of – kept me going. To say, you know, just the element of someone that you respect someone that’s a bit older, looking at you and saying: “This is good.”

I mean, it was a powerful thing. And I think yeah, you know, at different points… that I’ve had my eye on different people I’m trying to impress… And usually it’s – Okay, here’s the form of this poet – and taking me on, and, alright: “I’m gonna write those sonnets! They’re gonna be so good! They really like sonnets! I’m gonna write, like, an iambic beat here… I’m gonna do four turns in this one!” And the funny thing is… like with most things in life, when you when you try and impress someone, you know, that the try-hard thing – it never really works. I gave them the poems, all like, I was so sure: “You’re gonna love me now!” and they’d just be like: “…Huh? What happened to the other thing you were writing?” And it’s just like: “Oh…”

Chris Gribble 4:52

Fascinating. There’s something… there’s some sort of nice symmetry with the teacher/pupil relationship on one side – And there’s the parent/child, as you’ve already said, and there’s the therapist/patient as well. There are all of these forces that are being unleashed in mentoring and some of them are about resistance and fighting back. It’s a… it’s a fascinating dynamic because a lot of–

Raymond Antrobus 5:15

Yeah, no, that’s true what you say about resistance, because, as well, like marking your kind of space, your territory, is also marking “enemies” might be a hard word… but you also want, you know, you have an idea of what you’re pushing against, as well as what you’re pushing towards. It’s interesting. I realised that it is as important to have something to push against as it is to have something to pull towards.

Chris Gribble 5:45

I have a friend who is a very successful prose writer, and she’s an incredibly positive and generous person. I was talking to her about just this thing once and she sort of turned around and said: “But, you know, I do also want to crush the faces of my enemies into the dust!”

Raymond Antrobus 6:03

(Laughs) Yeah, totally. Yeah.

Chris Gribble 6:08

I think one of the reasons that I’m asking you about these particular moments in your career. It’s because, partly, I feel like I’ve seen… I’ve been witness to your career for quite a long time. You won’t know this, and don’t feel threatened by it – I’m just a poetry reader, honestly! But your first full collection was published by Tom Chivers at Penned in the Margins. And I’ve been kind of around Tom since the start of that, and watched that with huge admiration – Now how was that as an experience, and what did that book do for you?

Raymond Antrobus 6:38

Oh, you know, so The Perseverance, and the whole experience of writing that book was so damn emotional, and so private, and so – like what I just said about… I had a very clear idea about who my enemies were and what I was pushing against. And the kind of allegiances I was wanting to signal, you know, it was it was meant to be a very much kind of like: “I have arrived, I’ve realised something.” Because I was trying to write that for so long, and there was just – a spark. The whole time was just a blur. Because I wrote a pamphlet about a year before and that’s just came out, and actually that felt like an important book to write, it felt important to just jump straight into the next thing – and that became The Perseverance. I mean I have a different perspective of it now, but speaking at the time it was like – A: I had no experience of the publishing world, really. At that point people… To Sweeten Bitter was put out by Outspoken Press, and the publisher/editor was literally a friend of mine. There was no, like—

Chris Gribble 6:43

It was DIY–

Raymond Antrobus 6:44

Yeah, exactly. Same with… I published two pamphlets, one in 2012 with Burning Eye Press (Books) and when I self-published something in 2011 called The… For a very short time I went by the name of “Educated Fool,” which was a reference to a Bob Marley lyric. My dad used to sing that lyric to me a lot, so I kind of adopted it – but whatever, that’s a different story. But that book – The Perseverance – I had no, to be honest, I had no real kind of professional expectation of it. I just had this very… urgent energy, to like, get it, to like to write through this and get through this.

Yeah, it was a very cathartic thing actually. And then when it was out in the world, really, I really did feel like releasing… People – I know it’s a cliche but giving that part of yourself away… you know, you detach from it, like, it’s yours – go out! And the way that that book then moved through the world since has been… to this day, actually – It just, it just keeps giving me back messages and people, and just yesterday on Instagram… I worked in 2006, I went to the States, I went to Ohio, and I worked with a group of deaf and hard of hearing children, and coders (the children of deaf adults,) so I was what eighteen? And just yesterday, one of the kids I’ve talked to, they sent me a message on Instagram with a picture of them holding The Perseverance… And it said: “I don’t know if you remember me, but you looked after me for a week. And I remember you said you want to write poetry I cannot tell you what it means to see you follow through on your dream.”

Yeah, it was so emotional. And the thing is, I’ve had quite a few things, like… teachers who have remembered me have bought the book and reached out, and I’ve had… It’s just become this teleportation device in some ways, for me, and just given me so many opportunities so yeah, to reconnect with a lot of people… and speak to and from, you know, my growing up time… and all the different people in all different kinds of educational settings and literature settings… and, you know, and so I’m saying all this before I’m even talking about like, the prizes, and all what that kind of stuff did. Because I didn’t expect… I mean half the prizes that I was winning – I hadn’t even heard of! So, it was like: “Oh, God, this is happening. This is happening…”

Chris Gribble

I think it’s still the only poetry book to win the Rathbones Folio Prize.

Raymond Antrobus 11:49

Yeah. Yeah. So that’s kind of that that that was that was a big one. That was a really big one.

I’d say that one of the most memorable kind of memories of that whole period. I got… I got shortlisted for this thing called the Griffon Prize in Canada. And that was at that point—

Chris Gribble

Yeah – It’s pretty enormous in terms of global poetry prizes. The curators, the prizes the judges, the wrap arounds, the ceremony. It’s huge.

Raymond Antrobus 12:12

It’s pretty it’s pretty much like how… what it must look like when you’re, you know… up for a Nobel or something.

And so, walking into this grand hall – there are literally thousands of people who are in the audience. And you’re at the podium… and I just had this kind of moment where it was like… I wasn’t even thinking about winning. It was just a kind of thing of being like: “Look where I am, look where a book has taken me… look at the company it has given me.” All the other poets on that shortlist were just amazing, just beautiful people, as well as excellent writers and poets, thinkers, and intellectuals. You know, and I think I think that moves me, maybe the most out the whole thing… Was the fact that I didn’t know a single person. I didn’t I never heard of the any of the judges, any of the jury! Someone at the other side of the world… this group of people had read the book, completely detached from me. So, there was no kind of – Yeah, it was just like, it was… I needed to see that because I think I needed to feel that there was real merit in the work.

Chris Gribble 13:34

Another point of recognition. A sort of approbation, a sort of freedom in a way… From yourself and your own anxiety.

Raymond Antrobus 14:03

Yeah, all of that. And you know that experience kind of quelled a bit for me, and that, you know, prizes do – the validation that you can feel with prizes is a very powerful thing.

But I’d say that the validation I felt just being shortlisted for that award. In Toronto, in Canada, in this whole other space! Was really powerful. And I think really gave me more confidence as a writer, as a poet — because I came back and went straight to work on the next book. With a feeling of invigoration and inspiration and excitement: “I’m going to carry on, I’m going to write a better book, a more slender book that’s kind of… a wider lens! and I’m going to kind of write… I’m going to embrace the uncertainty and create a kind of poetic with that.”

I’m proud of that second book as well. I finished a third book now, and I’m kind of like – cool! I’m gonna use the “J word” again, this is a journey, you know, every book is… it’s almost like a time capsule. Its own milestone, its own energy, its own experience – you know?

Chris Gribble

It reflects the entire world. As a reader, there’s an obvious umbilical connection between The Perseverance and All The Names Given. But one of the major things that comes off it – is many fewer inhibitions and much more confidence in All The Names Given. Tell us a little bit about that book, it’s a few years old now?

Raymond Antrobus 15:41

Yeah, two years… three and a half? Oh, yeah, it’s funny, it came out in 2021. Yeah. I wrote it in 2020… those books take ages to come out. Yeah. So, one of the big differences… One of the, I guess, most fundamental difference with All The Names Given – in the UK it’s published by Picador where my editor was Don Paterson. The thing is, I’ve been a massive secret fan of Don Paterson for a long time. I don’t really recall ever having a conversation with… If anyone had been like: “Don Paterson is the man…!” You know, from when I read his collection Rain… and just was like… “This, someone really up to something really interesting.” I think I was drawn to how Don writes – with such, I think sometimes, his wit and his humour, marks a vulnerability with masculinity in particular, and especially how he takes on the kind of… You know, he talks about parents. So, he writes about being a son, and a father, in ways that I find really endearing. And so anyway, when I heard that Don liked The Perseverance I kind of couldn’t believe that. Because I’ve had public stuff about certain poets who’d come from my world at that time, with open mic stands and performance – and Don got some flak for supporting them. So, when I heard that Don was interested in publishing my next book I just thought: “He’s gonna hate it. But this is what it is.” And I sent it to him, and he got back to me… The thing that we connected with, the first poem I sent to him, was one that wasn’t actually in the book. It was about my grandfather.

So, one of the things that Don and I connected with was that both of our grandfathers were ministers. They were preachers. And yeah, we just had this long conversation about what we felt… how that might have kind of influenced us. What that kind of meant. Coming from that position and I was trying to write these poems about that… I think, only one of them ended up in the book. I really appreciate Don’s honesty, as well. You know, I think that finding critical honesty is actually very difficult, because people don’t want to upset you. People are nice, aren’t they? They’re so nice! But that really… You don’t want a nice editor – kind of like how you don’t really want a nice therapist! You know, you want someone who knows how to be honest, and—

Chris Gribble

Who can land a criticism without forging their own agenda.

Raymond Antrobus 19:33

Right. Exactly. Exactly. And there is such thing as loving criticism, right?

Chris Gribble

Yeah.

Raymond Antrobus 19:42

Unfortunately, it’s really hard to find. And it’s often a very skilled, experienced person to deliver that. So, I think found that in Don, actually, for this book, I… for example, you know… I know that there were poems in that book that he didn’t want in, and there were poems in the book that I didn’t want in. And it became this kind of tussle actually, and I think the book was better for that. I think it was made a bit more rounded for that. And I think, yeah, I think I grew as a poet for writing that.

And to be honest, I really wanted to write away from The Perseverance. So, I wanted to get a book away from it. So now I’ve written the next book, which is coming – I can really see All The Names Given as like a transitional book… into something else. I’ve got a different editor at Picador now – Colette Bryce, who’s different…

Chris Gribble 20:48

So super sharp–

Raymond Antrobus

Yeah. Yes. An excellent reader, a gifted reader, like just the way that she can… Yeah, she sees things! You can’t hide from Colette, and again, it’s another hallmark of an excellent editor. They can tell when you’re hiding.

Chris Gribble

I think one of the things that attracts me to Don’s writing (and I don’t know him at all!) Is that he’s an autodidact, he’s self-taught. Which brings a vulnerability to things which is both really attractive at times and sometimes really sort of quite shocking and – spiky.

Raymond Antrobus

Spiky! Yeah, totally. Totally!

Chris Gribble 21:31

For me, it presents around class and expectation. I come from a working-class background and ex-mining village in Newcastle. Kind of seeing – Don’s sort of… and I found a way through to university where I stayed for a really long time doing several degrees in a row and thinking I was going to be an academic and then realising… Kind of, what I found in Don’s writing was this absolute expectation that he should have access to all of that knowledge. And I find that incredibly liberating.

Raymond Antrobus 22:05

Yeah, no, I yeah, I really resonated with that as well. Yeah, for sure. Yeah. Also, somebody that had quite unconventional upbringing, where money was not a thing.

But in a strange way, kind of so many things I value about, I guess myself, my life, and the person I am kind of is born and bred off that navigation. Yeah, it’s tricky.

Chris Gribble 22:40

Do you want to tell us a little bit about your next book? And when it’s going to be out?

Raymond Antrobus

Sure. So, for next one is going to be out. Autumn 2024.

It is a book, which is a hybrid book – in that it’s a mix of poetry and auto-fiction.

I wanted to do something which – Yeah, I kind of wanted to lean on to a few other modes of writing. And yeah, they’re kind of this kind of auto-fiction thing came out because – I became a dad! So, my whole writing rhythm to change and to shift – and what I would find myself doing was the first year… of actually through the pregnancy as well – through my wife’s pregnancy, particularly for the last trimester… We were, you know, we were living in like three different countries, three different parts of the world. So, New Orleans and then Oklahoma, in the States, and then finally came back to UK.

And while I was kind of moving around the cities and those locations, I was snatching writing time. So the two poets I thought a lot about in terms of an anchor kind of, you know, an anchoring of the mode was – William Wordsworth, because Wordsworth had such… It seems to me anyway – such precision and vision in his lyric. There’s a constant… elusion… to nature, obviously. So grounded and concerned with trees. And how there were all these – several Romantic poets, that should have been assigned a tree. And so, Wordsworth’s tree which is the ewe tree. I really like that idea of having a direction and that being as specific as a tree. So yeah, obviously the questioning and the curiosity of Wordsworth, which is: “What is our place in this world, in this nature? Should we even be in conversation with nature, are we meant to just… Is it just God that we need to worship?”

And then there is the other poet that I drew a lot from and grounded the poetics in for this book. It was Lucille Clifton. She’s a poet from Baltimore in the US, died in 2010. But her poems are always very slender, short poems because she had eight children. So, she was writing these poems while she was child rearing and raising the kids. And so, the practice of raising children fit exactly the mode of poetry that she wrote. And so, I just fitted towards that as a kind of, yeah, again, a mode, a tone, a kind of way to move through a time which is very delirious. Not getting any sleep.

So, it’s a book like sequence, in which all… Not all of them, but a selection of the poems that I wrote through… particularly over the first six months of my wife’s pregnancy, and then the first six months of my son’s life… kind of fuse together and make this kind of, again, like delirious… the “J word” again – journey!

Through… again, that particular time – and I think that I realised I had a book when I understood – a time that has been kind of encapsulated here. So I’ve read it through, all the way through it the other day, and there was like, I felt resolved – because it was kind of like, yeah, I’m kind of out of that now. Out of that period. My son is almost two years old now. So yeah, it feels like I’ve got as close as I could to honour that strange, scary, amazing, beautiful overwhelming time.

Chris Gribble

And what will the collection be called?

Raymond Antrobus 27:45

Oooh, I can’t say – I can’t say yet. Picador will announce it soon…

Chris Gribble

We look forward to reading it when it’s out. And the other two books that are coming out in the meantime?

Raymond Antrobus

A children’s book will be out it’s called Terrible Horses. It’s a children’s picture book.

Chris Gribble 28:00

Of course, you did Can Bears Ski? With Norfolk’s – Suffolk’s! Polly Dunbar.

Raymond Antrobus 28:05

Yeah! Yeah, this is a very different story. Terrible Horses, I’m equally proud of it. Then I have a non-fiction book coming out in 2025. Which interestingly enough – it’s being done by the same people who did Don’s memoir. So that so been talking quite a bit about… you know, the process of poets writing prose, and specifically by writing kind of experimental memoirs or writing prose as poets. Does that make sense?

Chris Gribble

Yeah. We had Amy Key with us this morning, Talking about her recent memoir as well. It was a great event – hopefully we’ll record it!

Anyway – So you’re going to be reading for us at the Rialto event this evening—

Raymond Antrobus

Yes!

Chris Gribble

It’s going to be a fantastic celebration of Rialto Magazine. This podcast by the time it’s out – in maybe a couple of months’ time… But just want to thank you so much for coming and joining us today. I could’ve talked to you for a lot longer. It’s just a great pleasure to welcome you to The Writing Life.

Raymond Antrobus

An honour! An honour to be here. I just want to say that tonight, right? What I’m gonna do is – I have a loose idea, but I’m reading poems that aren’t published. But thinking of it as, like, that these are poems I’m kind of proposing for publication to Rialto. Right? I’m putting these poems in an envelope, I’m auditioning them. If the editors of Rialto are interested – these aren’t published yet!

Chris Gribble 29:32

I should go tap them on the shoulder as they go around this evening and let them know – That there’s an opportunity to have a conversation.

Raymond Antrobus

(Laughs) There we go!

Chris Gribble

Glad to play a part!

(End of interview)

Steph McKenna

A big thank you to Chris and Raymond for their time, and make sure to visit raymondantrobus.com to check out more of his work.

If you have any questions or you want to get in touch you can find us @WritersCentre on Twitter and Instagram, we’re on Facebook, and you can sign up to the NCW newsletter at nationalcentreforwriting.org.uk.

As a UK registered charity, we rely on the generosity of our supporters to make our work possible. You can make a donation over on the website by going to the Support Us page.

Please do subscribe to the podcast and leave a rating and a review because it helps other people to find us.

Thanks again, keep writing, I’ll catch you on the next episode.

You may also like...

PODCAST: Common ground: writing, culture and community in Singapore

On understanding across social, cultural and linguistic borders

6th February 2023

PODCAST: How To Balance Story And Plot

Writer and lecturer Ashley Hickson-Lovence explains how to balance plot and story.

18th July 2022

PODCAST: How To Structure A Novel

Writer and lecturer Ian Nettleton explains how to structure a novel: the devices and structural elements that can keep readers engaged and how to ensure your story becomes a page-turner.

27th June 2022