Read ko ko thett’s fulfilling account of leading one of our online Link the Wor(l)ds translation workshops.

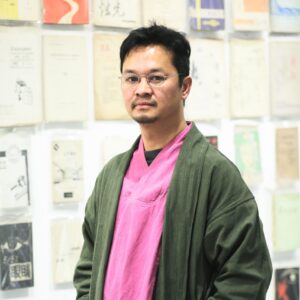

In 2022, NCW partnered with PEN Myanmar, the Singapore Book Council, the Goethe Institut in Yangon and the Frankfurt Book Fair to run an online edition of the Link the Wor(l)ds translation workshop. In previous years, the workshops have taken place in Yangon, but as this was no longer possible, we decided to bring everyone together online. There were four translation workshops – two from English to Burmese, one from German to Burmese, and one from Burmese to English, led by the poet, translator and editor ko ko thett. Here he talks about the experience.

Linked Worlds: Translating from Burmese to English in Post-coup Myanmar

Over a steamy coffee on a chilly morning in Norwich in February 2022, NCW’s Kate Griffin suggested that I lead an online Burmese-English literary translation workshop, as part of the Link the Worlds translation course that would also feature German-Burmese and English-Burmese workshops. The online workshops were going to be the first of its kind in Myanmar. I loved the idea, but wondered how an online workshop for Myanmar could be realised, given the circumstances the country was in.

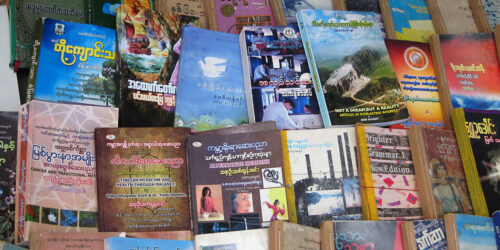

Since the military coup in February 2021, Myanmar had seen widespread conflict. The junta had routinely blocked the internet in some parts of the country. Though much of the Myanmar literati continued to be visible on social media, the publishing industry, that was booming before the coup, suffered a severe setback as the low-income country tumbled further down the abyss of poverty. Our facilitators in Yangon made a generous offer that expenses for the internet would be reimbursed for the participants from Myanmar. There were eighteen finalists from all over the country who were vying for five spots in my workshop alone. I made my picks, on a second test and the different regions of Myanmar the candidates represented.

The course began in July 2022. Inspired by the BCLT summer school model, we were to come up with a ‘consensus translation’ of a short story by the Mandalay writer Chaw Ei Mahn, who would be available through the sessions so we could consult with her if need be. Her story, Koyin Ngabein [Ngabein the Scrawny Novice], is a tale of discipline and punishment, set at a Buddhist monastery in Mandalay. The story highlights the bond between sayadaw, the head of the monastery, and his koyin or novices, as much as that between senior monks or kodaw who had studied and boarded at the same monasteries.

‘decolonial translation’… gives more agency or power to translator as it acknowledges translator as creative writer

The story also sheds light on how novices from impoverished backgrounds from rural Myanmar are recruited into the sangha or the order of the Buddhist monks, and the hardship koyin — children as young as four years old, had to endure during their studies. The real challenges of the story, however, were frequent occurrences of numerous Burmese Buddhist terms, that indicate one’s place in the monastic hierarchy. They have no English equivalences.

To the workshop I recommended ‘decolonial translation’ championed by Dr. Nazry Bahrawi of University of Washington, Seattle. In my opinion, ‘decolonial translation’ has three distinct advantages; it makes the translator visible by making the source language visible, it gives more agency or power to translator as it acknowledges translator as creative writer, and it questions values and norms of literary translation widely accepted in Western literary traditions and markets. Dr. Bahrawi, who appeared as guest speaker towards the end of the workshop, mentioned that terms of endearment or terms relationship should be foreignised. A case in point is the Burmese terms ဖေဖေ [phayphay] and မေမေ [maymay] that are usually translated as father and mother, or daddy and mommy. The Burmese notions of ဖေဖေ, မေမေ is not the same as father, mother inasmuch father, mother is not the same as ဖေဖေ, မေမေ.

Though much of the workshops was conducted in Burmese, all six participants spoke excellent English and they were all multilingual. Two of them, Bryony and Chel, spoke like native English speakers. It turned out that Bryony was not Burmese at all! She was a humanitarian worker from Canada, working in Myanmar. Chel was Burmese, with a perfect American accent, which she had acquired working for an American organization.

Arkar, a poet of redoubtable talent, had earned an MA in English from Yadanabon University in Mandalay. He loved quaint expressions, such as ‘lush’ for a ‘drunkard’ and ‘peaked’ for ‘pale from an illness or fatigue.’ Ma Lwin’s background was in legal and technical translations. Phyu was always brimming with energy and would always be the first to submit homework. The last one, Olivia, was about to become a lawyer, but the 2021 coup had dashed her dreams and she decided to become a literary translator.

I asked my workshop participants to work in tandem on different parts of the story. Bryony kindly agreed to be our in-house editor, and we were able to use several editorial insights from Dr. Bahrawi, who proposed that we submit the translation to a literary journal he was guest-editing.

I thank Kate for the initiative, and our facilitators in Yangon for linking my world with those of my workshop participants

One of the highlights of the entire project was a presentation by Thett Su San, who discussed technical and theoretical challenges in Burmese-English literary translation, based on her MA dissertation at the University of East Anglia. Her presentation on the untranslatability of Burmese euphonic expressions was attended by over fifty, including participants from German-Burmese and Burmese-English workshops as well as many other writers and translators. At the final session in October 2022 the three workshops presented their translations and compared notes.

As I write this in February 2023, exactly a year after my meeting with Kate over a coffee, I fondly recall the three-hour workshops that would usually go beyond 5:00 pm GMT (10:30 pm Myanmar time). I thank Kate for the initiative, and our facilitators in Yangon for linking my world with those of my workshop participants, who had managed to stay sane, purposeful, hopeful and even humorous in the face of seemingly insurmountable adversities in their homeland.

ko ko thett is a bilingual poet with several collections of poetry and poetry translations, in Burmese and English, under his belt. ko ko thett has been featured at a number of literary events, from Sharjah to Shanghai, and his poems and translations have appeared in literary journals worldwide, from Griffith Review to Granta, translated into several languages and are widely anthologized. His most recent poetry collection is Bamboophobia (Zephyr Press, 2022).

You may also like...

‘It’s a cliché, but there is an impossibility at the heart of translation’

Swedish author Golnaz Hashemzadeh Bonde in conversation with translator, poet and editor Elizabeth Clark Wessel

29th September 2020