Explore a creative response to scientific research in this Translating Science commission.

Translating Science is a collaborative project which brings seven scientists from the Norwich Research Park together with established writers so that experts within two very different fields of work can gain fresh insight and inspiration from each other.

The scientist welcomed the writer into their world and explained their research, and the writer then went away and responded creatively to what they were shown. The result is a series of stories, poems and essays which will hopefully inspire, excite and trigger a deeper understanding of the benefits of science-based research for solving the many challenges we face, and help to influence policy and decision makers to make the right choices. Read through the rest of our commissions →

Microfictions

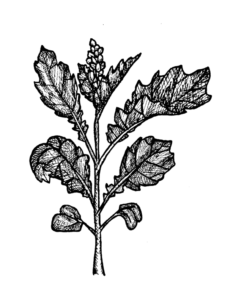

Live literature performer and non-fiction writer Jess Morgan has written a collection of microfictions in response to Dr Bethany Nichols’ work at the John Innes Centre, which seeks to understand how plant behaviour and development is impacted by the environment. Bethany is also an artist and contributed the illustrations that go alongside Jess’ creative pieces.

Jess said:

‘This microcollection of microfictions is based on six identified stages of the development of Brassica Napus, researched by Dr Bethany Nichols using artificial intelligence and computational methods to gather trait information.

‘Each story is separate but connected, and even expressed as microfiction (a story typically formed in less than 1,000 words,) is a long-hand and analogue expression of an idea. I have taken this cue directly from the research data collection method, which I have understood as computers taking pictures of plants at regular intervals, and being taught to measure aspects such as pod growth using pixels. In a sense, its limitations and ‘analogue-ness’ are its strength.

‘The stories are planted with language borrowed from the research described to me, for example, ‘Ground Truth’ – a term meaning a direct observation by a human, as opposed to artificial intelligence. I have also repurposed a number of fixtures, for example, a striped, tinsel-like graph known as a ‘Manhattan Plot’ and the location, Aberystwyth where plant data is captured by humans (G01, G02, etc) and via computer (C01, C02 etc).

‘In each of the six new contexts I hope to have echoed both the growth stage of the Brassica Napus and the interplay between research which appears to be structured and computer driven, and the human capacity for joy – not least in the greater hope of understanding how plants might withstand climate change.’

‘sometimes knowing if something doesn’t work, is as good as knowing something does. — Dr. Bethany Nichols

Ground Truth

Do you remember how to age a hedge? G01* asks. We talked about it last time. But G05° shrugs and says nothing. You can do it by counting the number of species in a thirty yard stretch. G05 scoffs. Yard? Who talks about yards? It isn’t really a question he thinks and so G01 doesn’t bother to answer. Here looks like a good spot, G01 says. The tree is a good marker. He points at an Oak tree overrun with deep green lobed leaves. Looks healthy. It’ll be here long after we’ve gone! G05 continues to stare through his phone screen. He sees how he uses two thumbs to type, like he had noticed all the young ones do. Far more use to the planet than you or I this fella. It’d take hundreds of years to replace him. G05 shakes his head. He doesn’t look up. It’ll be too easy, he says, flat. It should be harder to find. In the middle somewhere. G01’s eyes search the field, populated with green plants not yet in flower. He sighs. We’re not really supposed to mate – it’s not our land – we should stay to the edges. Those there, he points, are Brassicas. We mustn’t trample them. You know what they are? G05 only shrugs. He thinks they look like weeds. But he gets it. And if he just waits, his dad will tell him what they are, and save him the bother. He goes back to his phone. And G01 explains: This field will be bright yellow in a week or two. You’ll know the smell. Let’s bury it by the tree. What did you bring to put in it this time? he asks, dropping down to a crouch beneath the Oak tree and unscrewing the lid of a metal coffee tin. They’d hunted caches all over the Orkney islands, after the Neolithic site after Neolithic site had all started to roll into one and the rain seemed like it wouldn’t ever end. It’d rescued the trip. And for a while after, they’d both been hooked – hiding containers in the woods and on the edges fields just like this on weekends. But now, the boy was losing interest. The usual rubbish, G05 sighs, as G01 pulls an envelope from his rucksack. A few printed photographs spill out, as well as a smaller envelope. G05 frowns at the pile. And G01 senses it. What if we put something different in this one? G01 says. I brought some things – see – some of your hair! We cut it off when you were a baby. He dangles it in front of G05’s eyes, in front of

his phone. Annoyed, 05 pretends not to have noticed the little curl of sandy blonde baby-hair in his face. 01 has more. Your essay on climate change, he starts. But G05 snatches at the paper. You can’t put that in! But it was really good! G01 protests, as G05 folds the essay up so tight in his arms that it is hidden from sight. The boy crouches into his knees. His words muffled by his clothes. It’s not the right sort of thing, the says, as G01 arranges the collection of pocket sized objects on top of his backpack. You’re not allowed to put money in! G05’s eyes widen at the small pile of coins weighing down a number of magazine cuttings, and a packet of wildflower seeds. What’s the point of that? G05 huffs at the seeds. And it is G01’s turn to shrug. Might be a good idea? he says, and grins. I like this picture of us. Do you remember? That summer when you would only wear black. Look at you! He laughs. You were sweating! G05 grabs at the photo in the pile sending a use less plastic pin-badge spinning like a tiny frisbee, as coins disappear into the leggy grass. I don’t want people to see that! His dad risks his hand on the young man’s shoulder once more, saying softly, Put your phone away, please. And the boy does. What if we think of it more like a time capsule. Just for us. But the boy breaks away. We already did that at school. No one even cared when they pulled it up. It was stupid! Just full of stupid things! The whole thing was stupid. His dad wonders what was so bad about it to make his son spit out the word stupid that way. But he forgets it. Then we won’t dig it up. Not ever? He shakes his head. No. We’ll just leave it. It’ll stay buried, until the roots of this tree lift up, and believe me there’d have to be some good reason for that. Whispering now, he adds, and we’ll probably be dead by then.

Road Trip to Aberystwyth

We used to wear white coats. Bump shoulders. Lend pens. Big Steve used to make cakes, calling them his experiments. He had one of those rotating cake stands at home. For icing with a great flat knife, like drywall. The flour still in his beard at nine o’clock signalled he’d been at it all morning. I still think about scoring the parameters of a nice big slice, and pulling it out heavy and slow on the side of the knife, like a small birth. Instead I tear the clear wrapper off a small, very portable cereal bar next to me, same as every day. Tastes like paper.

There used to be fish in the pond. Just there, they say to visitors getting the guided tour, where the paving slabs are much cleaner, – there used to be a Ginkgo tree. A Chinese symbol of longevity, I heard someone replied, just once.

Halfway to the greenhouses now. It’s cost me two days holiday. But will still be carried out like an official visit. They will want to give me a clip-on sort of badge. Call me by my title. I only want to smell things and touch what I’m allowed. Hum something, if they’ll dare to leave me there for any length of time.

The drive takes me all day. I find I know all the verses the Don McLean’s American Pie. It had become for a while, our small, private project. Steve used to say It’s about so much more than Buddy Holly, drying the day’s mugs next to me. A spotty boy scribbles something that isn’t my name onto the side of a coffee cup. But what if it is your name?

He would have planned this trip by train. Brought a Thermos. Be the first to boom Caws! as a pre-flowering brassica shunts along the conveyer ahead of having its picture taken and its measurements captured. He would want to count the pods by eye anyway, un – dau – tri – pedwar – having learned Welsh especially for the trip, and for the plants as much as anybody. He believed they were deserving of music and that they were each multicolour-striped* on their insides, as we all are. Wrapped up in tinsel under our coats.

The Tennessean

There is a picture of Elvis Presley taken by George Barker on June 10th 1958, for The Tennessean, hanging in the entrance to RCA Studio B, which is open for the public to take guided tours. The spot where Elvis stood is marked on the floor by an ‘x’ made from two pieces of blue electrical tape. They change it every other day because it gets so dirty.

At twenty-three years old, he was slight. So much that half the pilgrims, Southern tourists, pushing thick thighs against the metal turnstiles, mourn the opportunity to set another place at their tables and show him what a good meal looks like. These are the ones that notice the photo anyway, though it omits the usual details: shoulder-pads, sequins, swipe of mouth grease the amalgamation of sweat and chicken drumsticks. Young Elvis wears a grey shirt and he is clean lipped and light haired. Caught in a downward glance, at the telling of a joke his pastor would not approve.

The piano player knows it’ll be morning by the time he gets home, but it’s a good gig for a jobbing musician with babies at home. Elvis’ people always booked the second session of the day – so they could go over if they need to, and they always did. It’s what the tour-guides will tell you now.

The signal is always just one finger – a fresh take, another pass, load more tape, change the sheet music. His girlfriend is going to kill him, he knows, but he keeps on playing whatever they put in front of him. Soon, he thinks, he’ll hand her the money, she’ll let him sleep.

The other people in the picture, their arms thick with hair, short shirt sleeves in the Nashville heat, lean on in. To make sure the camera sees the gold band of a college football ring. A Rolex watch counting down the hours until this talented boy belongs not to them, but to the Army. Someone steps out to phone for more tape, more coffee, cigarette smoke gathers thick in the air. Ends pile in a glass ashtray balanced on top of the piano – lid open and the workings exposed.

Crossover

The Kale had gone way over. You said. Hardly bothered these last few days to glance out the window. At the roses that had grown crooked. Weeds risen like small hedges, making labyrinth of our circular patio, fit for a devil with goat-legs. You showed me the heel of your hand as if to push the disappointment long into next week.

That is why when you were out, I snipped off a leaf and put it in the water glass on my desk – to occasionally touch and to pinch because they are so much like baby’s hands. What if I go outside and collect all the leaves and spread them all out on our pillows?

Flattened them with heavy books and pushed them through the mechanical arms of a hole-punch. Working day and night at our dining table with a pile of kale leaves, cabbage leaves, the kohlrabi. Until I have sore elbows.

But I have amassed two large handfuls of confetti ready to disperse with abandon over the next pair of strangers I see dressed in wedding clothes – having leapt from my chair, sprinted at the sound of the bells. And afterwards, as thousands of yellow-green specks melt their way back to the earth, I’d slip home through the churchyard, distinguishable only by a blur in the periphery of their photographs. They will think they have caught a ghost.

Drop Off

If you return a key to someone, and they are not at home to take it, you should first put it in an envelope.

Keys are not be spilled about – to become lost – the cause of silent grudges – that last for ages – against even our nicest friends. Keys strewn across the city – the result of a boozy night out – snapped heel – dusted up – absorbed into wet pavements – toilet floors – backseat of the taxi that would finally agree to take us. Keys found weeks later beneath the torn lining of a handbag.

A spare key does much to undo mistrust of the neighbours. Thinning the walls, pulling hard to the left that way we used to look at each other as one click-locked the car and one dragged out the bins. She waters your plants while you are on holiday. You sweep the needles off the porch.

A good key is always ghosted by its sharp stick and twist.

But tells a parent, we are still –

With keys – exchanged – we have loved and un-loved. Added to the bundle; used until painful, pressed back into a hand naked, returns slowly to a former temperature. Change the locks if you have to.

If you return a key to someone, through the letter box, you should put it in an envelope or at the least, a folded piece of paper. It draws the eye, protects it from the dog, softens the landing when it’s all finally done.

Jess Morgan is a writer and a singer-songwriter from Acle, near Great Yarmouth, who has made a career penning gutsy modern folk song, touring the worlds darkest cafes and just once, the O2 Arena. Jess also has a MA in Creative Non Fiction, was shortlisted for the I’ll Show You Mine prize and longlisted for the Hinterland prize for non-fiction. Jess’ latest project joining music together with live literature, was backed by Arts Council England and will be developed further in 2022 with the support of the Inn Crowd rural arts programme. Through lockdown, Jess had been carefully drafting her book – about birdwatching and IVF.

Jess Morgan is a writer and a singer-songwriter from Acle, near Great Yarmouth, who has made a career penning gutsy modern folk song, touring the worlds darkest cafes and just once, the O2 Arena. Jess also has a MA in Creative Non Fiction, was shortlisted for the I’ll Show You Mine prize and longlisted for the Hinterland prize for non-fiction. Jess’ latest project joining music together with live literature, was backed by Arts Council England and will be developed further in 2022 with the support of the Inn Crowd rural arts programme. Through lockdown, Jess had been carefully drafting her book – about birdwatching and IVF.

Dr Bethany Nichols is a Computational Biologist and Turing Fellow, working at the John Innes Centre. Using AI and deep learning techniques, Bethany aims to extract plant feature data from images, so that they can be used in combination with genetic data, to unravel the genes regulating Brassica development. Her work is part of the Brassica, Rapeseed and Vegetable Optimisation (BRAVO) project, and will help to uncover how environmental conditions affect plant development.

Dr Bethany Nichols is a Computational Biologist and Turing Fellow, working at the John Innes Centre. Using AI and deep learning techniques, Bethany aims to extract plant feature data from images, so that they can be used in combination with genetic data, to unravel the genes regulating Brassica development. Her work is part of the Brassica, Rapeseed and Vegetable Optimisation (BRAVO) project, and will help to uncover how environmental conditions affect plant development.

You may also like...

Gut: It Grows!

A Translating Science Commission from author Alexander Gordon Smith, inspired by research from Dr. Federico Bernuzzi

3rd April 2023