Norwich: a literary timeline

- c1413 – Julian of Norwich wrote the first work in the English language authored by a woman

- 1608 – First civic provincial library established in Norwich

- 1701 – First provincial newspaper was established in Norwich

- 1802 – Harriet Martineau was born in Norwich, one of the world’s first female journalists

- 1850 – First city to implement the Public Library Act of 1850

- 1970 – Britain’s first and most famous Creative Writing MA founded at the University of East Anglia by Malcolm Bradbury and Angus Wilson

- 1989 – British Centre for Literary Translation founded in Norwich

- 2006 – Norwich becomes the first UK city to join the International Cities of Refuge Network

- 2018 – Norwich became home to the National Centre for Writing

A city with a radical history

Until the 18th century, Norwich was England’s second city. Sheltered within a protected area of outstanding natural beauty, this regional capital looks out from England’s east coast across the North Sea into mainland Europe and a multitude of trading links and cultural networks beyond.

The city’s Anglo-Saxon origins, overlaid with a Norman, medieval, early modern, Victorian, modern and postmodern urban scene, embodies both continuity and a unique cultural identity rooted in the cultivation of ideas, radical writing and literary experiment.

Creative activity has always sprung from native roots and Norwich famously follows its own instincts. But this cultural wellspring has been fed over nine centuries by an influx of outsiders who have brought in new ideas, new technologies and new talent.

The city’s reputation as a historic centre of dissent and free expression has led directly to its designation as a City of Refuge and a sanctuary for writers.

In the beginning

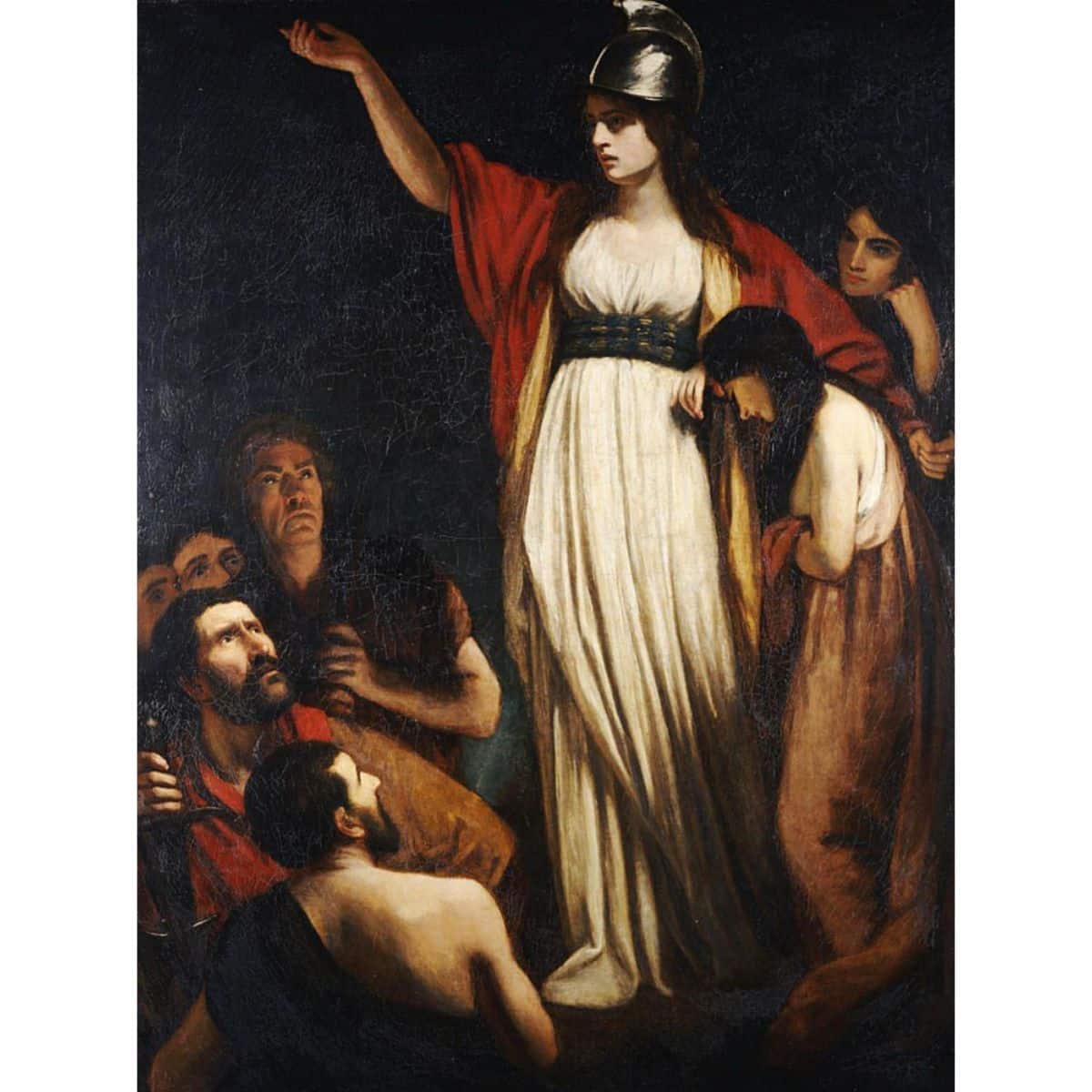

Norwich is a city of incomers, traders and refugees. The area has been a focus for human activity for 10,000 years and just beyond the city boundaries to the south, the Roman town of Venta Icenorum occupied the Iron Age home of the Iceni tribe who rebelled against Rome and were brutally defeated under their leader, Boudicca.

Two thousand years later, the myth of Boudicca has evolved to become a manifestation of national pride and a fiercely independent local spirit. Legions of storytellers, writers and poets tell her story in Norwich today.

Image: Queen Boudica by John Opie

A nexus of waterways

When Rome withdrew from England in the fifth century, Venta Icenorum was abandoned and Norwich emerged slowly from the watery marshlands around the confluence of two rivers, the Wensum and the Yare.

To understand Norwich is to enter the city by river from the direction of the North Sea, from the shores of Scandinavia, North Germany and the Low Countries. A nexus of waterways – the primary channels of communication – opened it up to trade, to foreign influences, languages, ideas and new technologies.

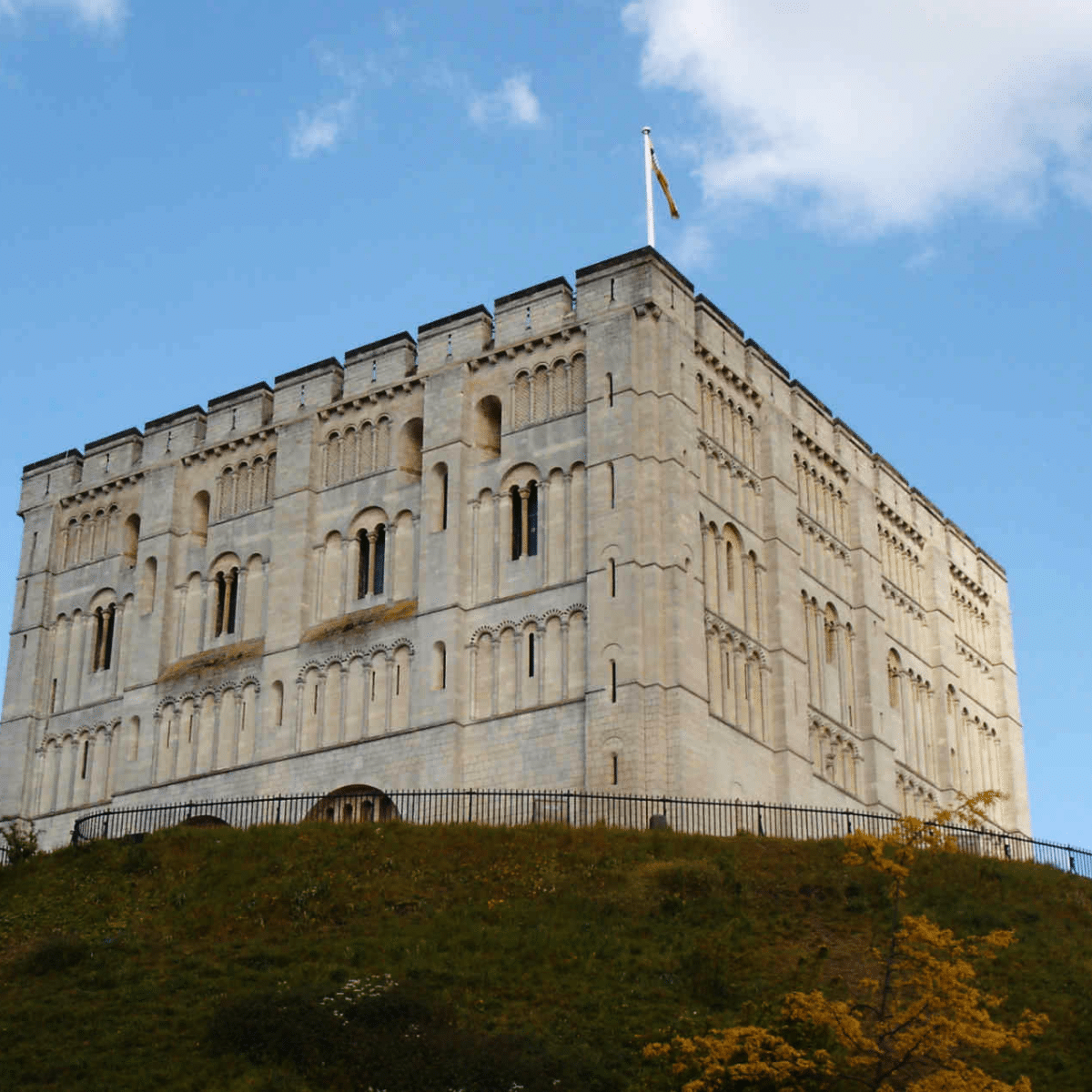

The Norman Conquest in 1066

By 1004, Norwich was important enough to attract the attention of Sweyn Forkbeard of Denmark who ‘came with his fleet to Norwich and completely burned and ravaged the borough’ (Anglo-Saxon Chronicle). By the time of the Norman Conquest in 1066, the town had recovered to become a major port and urban centre. With its close ties to continental Europe, it occupied the richest and most densely populated part of the British Isles and within the context of Saxon England, was home to the largest number of ‘free peasants’ – a prosperous, cosmopolitan region facing out to the wider world, able to assert some independence from feudal demands and the source of a free thinking, ‘du diffrunt’ culture still evident today.

The Norman Conquest brought dramatic changes to the settlement: a new borough for a fast-growing French-speaking population, including a significant Jewish quarter, a massive Norman Castle and a Norman Cathedral built across the old Saxon marketplace. In 1194, Norwich was granted a charter by King Richard I, making it one of the oldest ‘cities’ in the UK. Nine hundred years later, the castle, the cathedral and the market still dominate the city. Today, however, the castle is a museum of national importance and local affection and the cathedral is an international ecumenical, educational and inter-faith centre and one of the most beautiful buildings in England.

Exile and refuge

Norwich was a place of religious and political dissent and a haven for waves of refugees fleeing persecution in Europe. This potent mix of immigration and affluence continues to shape the city today and its physical expression remains in the grand architecture, winding medieval streets, human scale and European character that make Norwich such a good place to live.

The record, however, is ambivalent. The city’s reputation for tolerance, non-conformism and continentalism has been matched by episodes of intolerance and insularity. And this ambivalence goes back a long way. In 1144, the first blood libel in the history of European antisemitism was enacted in Norwich against the Jews, leading to massacres in London, Lincoln and York and eventually, to the expulsion of all Jews from England in 1290.

There is a memory in Norfolk as long as its Celtic shorelines. Since Norwich emerged from its watery landscape and wide skies, it has challenged writers to release that memory, as a form of imaginative history that flows into now and the future and carries with it the agonies and consequences of persecution and exile, the dynamic virtues of immigration and sanctuary and the joy of dreaming in a place where everything seems possible.

Meir ben Elijah’s voice cries out from the darkest period of Anglo-Jewish history.

Beyond the cathedral walls, Norwich was home to England’s only medieval Hebrew poet, Meir ben Elijah. Writing at the time of the Jewish expulsions in 1290, his voice cries out from the darkest period of Anglo-Jewish history. From the edge of oblivion, he attempts through his poems to sustain a connection to his home to which he would never return. His poems were ‘lost’ for 700 years, but as a direct result of research for this bid, they have been rediscovered and were published in translation in early 2012.

Mighty art Thou and glorious: Those in darkness dwelling Thou dost surround with Light.

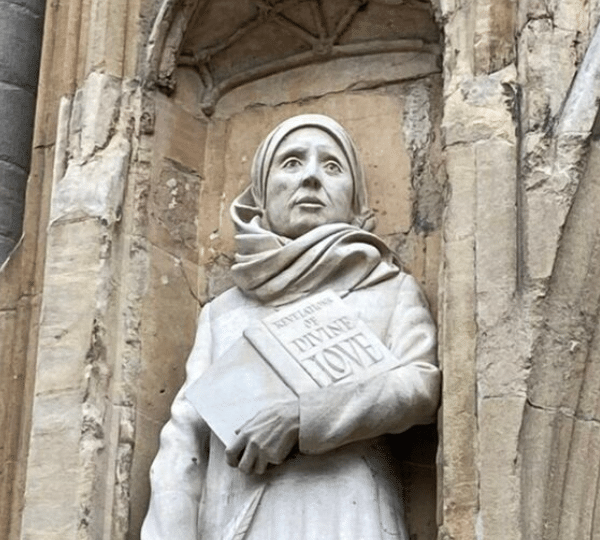

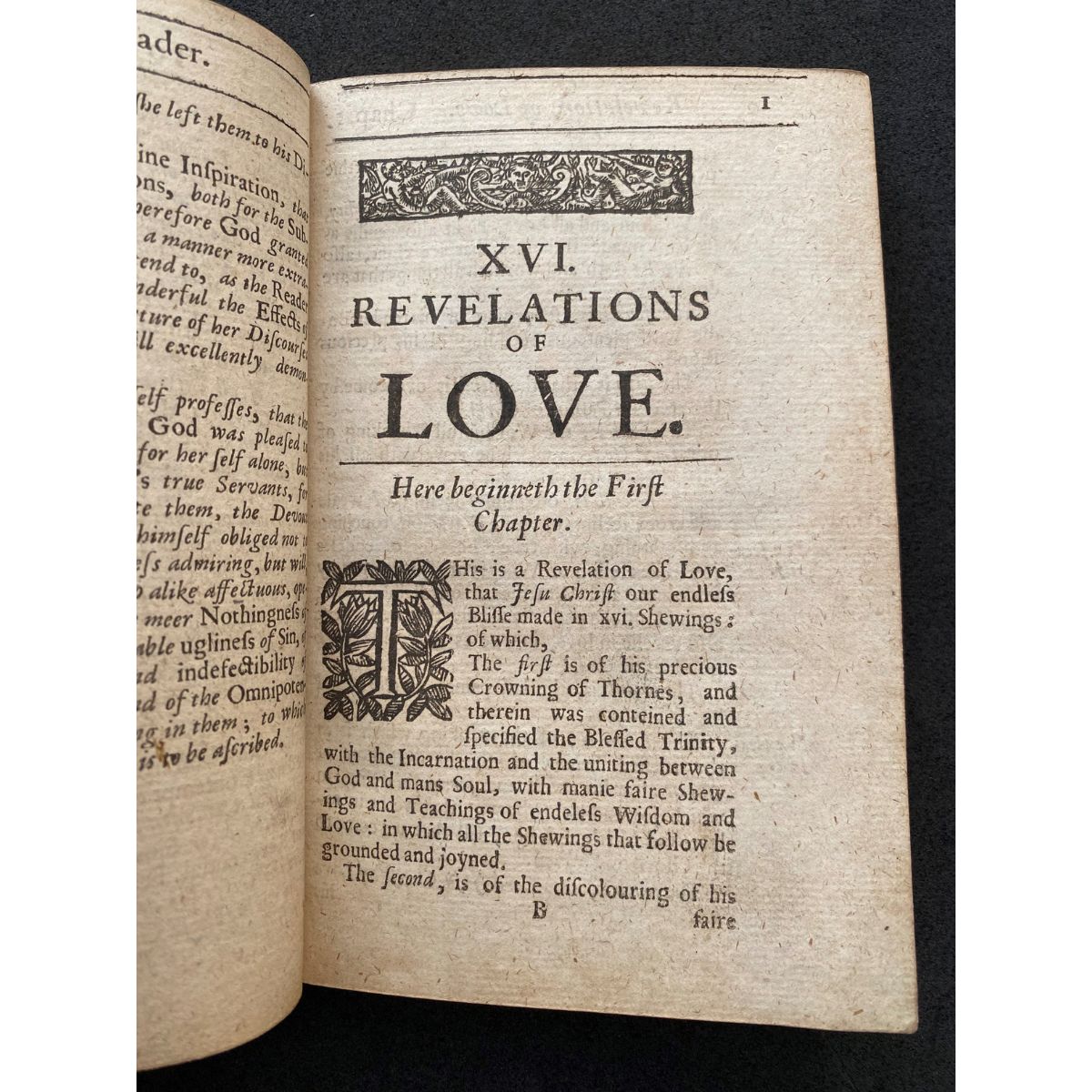

Julian of Norwich

Julian of Norwich (1342–1416) also spoke from a time of extreme personal and social crisis in a voice that still resonates today. One of Europe’s greatest mystics, Julian wrote one of the most astonishing texts of the Middle Ages and was the first woman to be published in English. Norwich had more than 50 churches – many of which survive today – and she spent most of her life walled up in an anchorite cell in St. Julian’s. Here she wrote Revelations of Divine Love, an extraordinary contemplation of universal love and hope in a time of bubonic plague, religious schism, uprisings and war.

This was also the time of a great flowering of vernacular English literature – Geoffrey Chaucer was a contemporary – though Julian was certainly the only writer who referred to God as Mother. Today, she is read by secular, contemplative, feminist and literary readers of every nationality and faith worldwide, attracting thousands of visitors to the place where she lived and wrote.

Image: Revelations of Divine Love © Strangers Hall

A city of Strangers

In the following centuries, Norwich continued to grow and the main source of wealth was wool and cloth exports. The success of the wool trade combined with a wide network of immigration links with continental Europe made the city rich and from the Middle Ages until the 18th century, Norwich was the second largest city in England.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Norwich became a haven for Dutch, Flemish, Walloon and Huguenot immigrants fleeing persecution in mainland Europe. Some 37% of the city’s population were ‘strangers’ – the highest ever concentration of refugees in a British city. As the cultural and economic centre of one of the most highly populated areas of the country, Norwich became a hotbed of new ideas, new forms of printing and literary expression, at the same time as another cultural flowering, sometimes referred to as the English Renaissance, reached its peak in the Elizabethan Age.

The play’s the thing

The city’s rumbustious playwrights and poets captured every opinion and literary style of the period.

Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (1517–1547), gave the world its first blank verse and sonnet form – later used by Shakespeare. (He was executed as a staunch Catholic at the time of the English Reformation.)

Playwright John Bale (1495–1563) was a famous propagandist for the Protestants.

Thomas Deloney (156?–1600) was a balladeer silk weaver who created the first prose narrative, recognisable today as ‘the novel’.

The dramatist, poet and pamphleteer, Robert Greene (c.1558–1592), accused the embryonic novelist of ‘yarking up ballads’ and called his contemporary, William Shakespeare, ‘an upstart crow’. And back at the cathedral, the Bishop of Norwich, Richard Corbet (1582–1635, left), wrote anti-Puritan verses and ballads.

All shall be well, and all shall be well and all manner of thing shall be well.

In print

In 1438, Johann Gutenberg invented one of the world’s greatest technologies, moveable type. By 1556 the exiled Flemish Protestant, Anthony de Solempne, had arrived in Norwich and was printing books for the city’s Dutch refugees. In 1701, Frances Burges launched Britain’s first provincial newspaper, the Norwich Post, and the region has been famous for print ever since. The small Norfolk town of Fakenham has been a centre for printing since the 18th century and Bungay, on the Norfolk/Suffolk border, is known worldwide as the home of Clays, one of the UK’s largest book printers with a workforce of 500 people producing 180 million books a year.

Amidst this maelstrom of literary insults, Norwich had become a city of print and in the great European age of maps and mapping, it was the first English city to be shown in prospect by the pioneer cartographer, William Cunningham. Remarkably, this magnificent plan of Norwich in 1558 is still visible today: a handsome, human-scale skyline punctuated by civic towers and spiritual spires.

The remarkable Jarrold family arrived in the East of England in the 17th century, bringing with them the art of printing and book-binding and an ethos devoted to civic life.

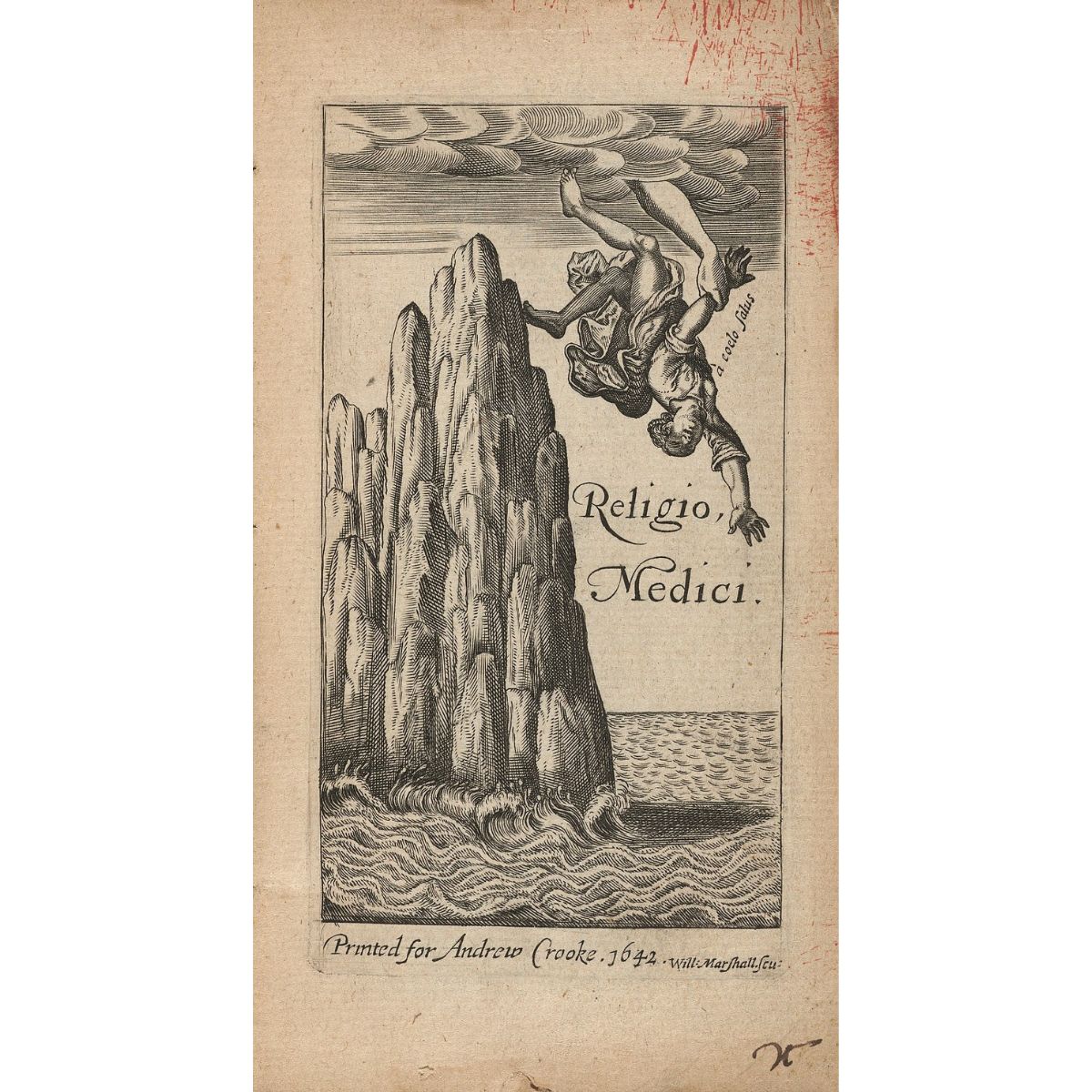

Also in the 17th century, during the English Civil War, the great polymath, physician, philosopher, scientist, naturalist, bibliophile and Norwich resident, Thomas Browne (1605–1682), wrote books of such universal distinction, his influence as a literary stylist over 400 years has transcended national boundaries. His private collection of books in many languages formed the foundation of the future British Library and his tomb, in the fabulous church of St. Peter Mancroft, attracts literary pilgrims from all over the world. Thomas Browne was revered, amongst many, by the Argentinian writer, Jorge Luis Borges (1899–1986) and the Norwich-based, German writer, WG (Max) Sebald (1944–2001), who founded the British Centre for Literary Translation at the University of East Anglia.

Image: Religio Medici by Thomas Browne © Houghton Library

‘Let any stranger find mee so pleasant a county, such good way, large heath, three such places as Norwich, Yar. and Lin. in any county of England, and I’ll bee once again a vagabond to visit them.’

Revolution in the air

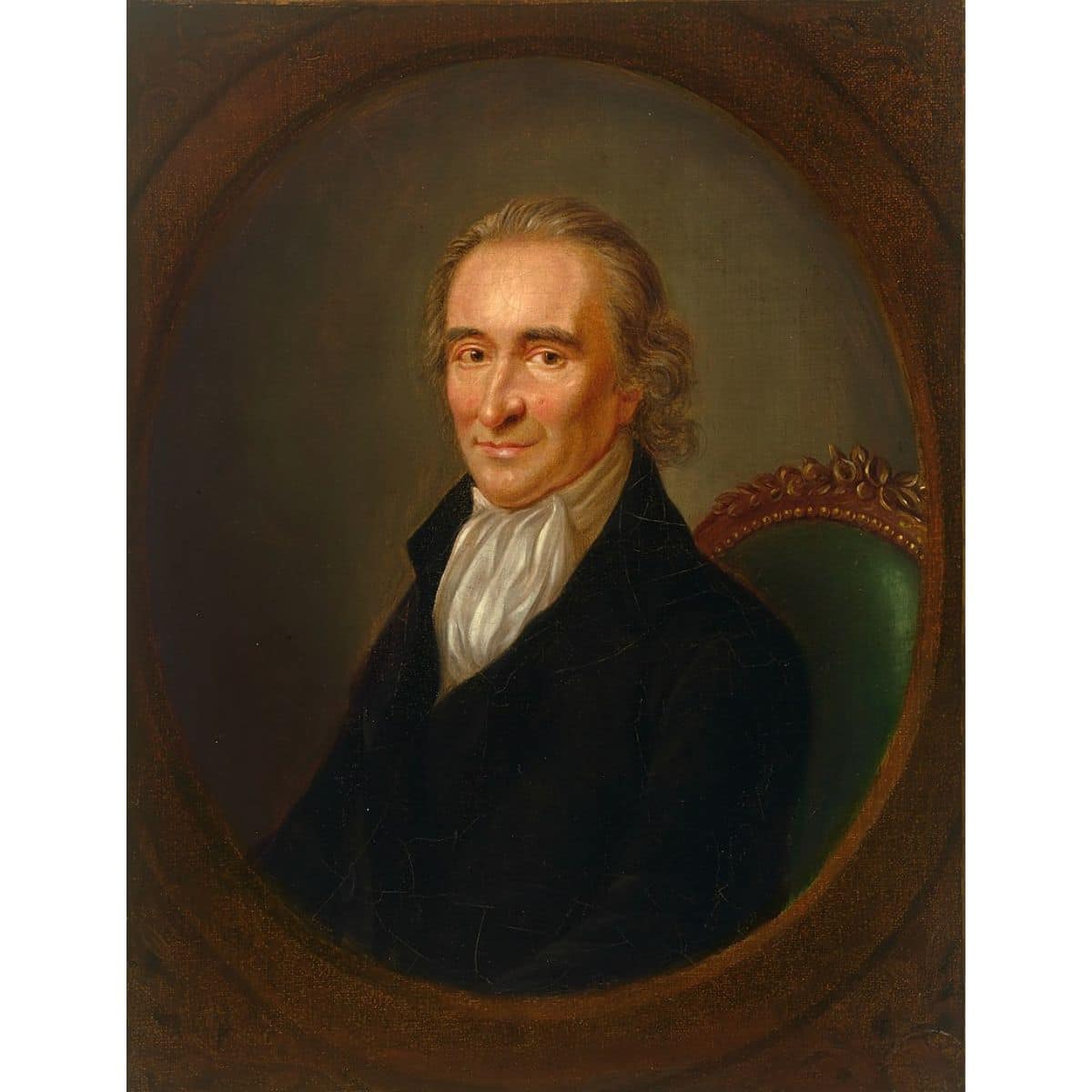

UEA is also home to the Thomas Paine Study Centre, named after one of the most influential political writers the world has ever seen.

Thomas Paine (1737–1809, left) was born of humble origins 30 miles south of Norwich. A friend of Benjamin Franklin, Paine’s Common Sense treatise (1776) influenced the course of the American Revolution and led to his involvement in the framing of the American Constitution.

Raised in a household of opposing religious views – his father was a Quaker, his mother a member of the Anglican Church – he became a sceptic, a restless character driven by an inner revolt against the inequality he had witnessed in England. He wrote passionately in support of the French Revolution and the abolition of slavery and his Rights of Man (1791) is one of the most widely read books of all time. Paine’s radicalism is both universal and very particular; a prime example of the dissenting mind that emerged through the centuries in Norfolk and Norwich as a force for change in the wider world.

Power to the people

As Thomas Paine campaigned for a new world order, a Norwich printer embarked on a career that would transform his name into a synonym for parliamentary democracy. Luke Hansard (1752–1828, left) learned the parliamentary principle as a child – his mother was a Tory and his father a Whig – and his fortune rose on the wave of political publishing that accompanied the intellectual revolution of the late 18th century.

Hansard excelled at the production of political tracts and broadsheets and on the strength of this work, he secured a job with John Hughes, printer to the House of Commons, who counted Dr Johnson and Edmund Burke among his customers. Hansard soon became a partner of the firm and by 1800, he was sole proprietor. His sons and grandsons consolidated the business, printing the Parliamentary Debates first for William Cobbett and after 1811, as Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates. Throughout the English-speaking world, the word ‘Hansard’ has come to represent public access to the democratic process and appropriately, Hansard is published in Norwich by The Stationery Office.

Image: Portrait of Thomas Paine by Laurent Dabos

A wider literary landscape

Norwich serves Norfolk as its main urban centre, but the county itself has thrown up some of England’s most striking literary figures.

- The English political philosopher and novelist, William Godwin (1756–1836) – the world’s first proponent of anarchism and utilitarianism – lived in the tiny hamlet of Guestwick

- Parson Woodforde (1740-1803), an unremarkable vicar, kept a remarkable diary of everyday rural life and became a 20th century bestseller

- Mary Mann (1848–1929), a farmer’s wife, was a quite unique Victorian author of 40 novels on rural poverty

- The ‘light of glory of English letters’, John Skelton (1460–1529) was the Tudor poet laureate who lived in South Norfolk

- Five hundred years later, another poet laureate, Andrew Motion, was Professor of Creative Writing at UEA

Literary Lioness

Harriet Martineau (1802–1876) was born in Norwich of Huguenot descent and radical Unitarian views. She found extraordinary international fame as a ‘literary lioness’, political economist, pioneering feminist, the world’s first female journalist and one of the founders of sociology.

In 1835 she set off on an intrepid tour of America to investigate how the young country was measuring up to its constitutional ideals. She travelled in the South, saw slavery at first hand and spoke out at a meeting of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society which led to mob protests and threats to her life.

On her return she wrote two books – Society in America and Retrospect of Western Travel – and Charles Darwin, much impressed by their famous and formidable author, became a close friend. Her radicalism and insistence on equality and human rights had an impact on many, particularly her novel based on the life of Haiti slave rebellion leader Toussaint L’Ouverture, The Hour and the Man (1856). She travelled to the Middle East and wrote the trilogy Eastern Life (1848) in which she predicted future conflict between East and West.

Norwich had produced another world-class writer: an individual voice and a genuine radical whose work in the cause of gender and racial equality, fair economics, scientific evidence and campaigning journalism, demonstrably changed the world.

Image: Harriet Martineau by Richard Evans

Norwich is a fine city. None finer. If there is another city in the United Kingdom with a school of painters named after it, a matchless modern art gallery, a university with a reputation for literary excellence which can boast Booker Prize-winning alumni, one of the grandest Romanesque cathedrals in the world, and an extraordinary new state-of-the-art library then I have yet to hear of it.

A home of radicals

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, Norwich was a radical centre for writing and publishing, for dissenters, revolutionaries, translators, internationalists and social reformers. Amongst Martineau’s abolitionist contemporaries were the great prison reformer, Elizabeth Fry and Anna Sewell, who wrote the 50-million bestseller, Black Beauty (1877) – one of the most translated and widely read books in the world.

At the same time, the novelist, travel writer and multi-linguist, George Borrow – protégé of the radical Norwich teacher, writer and linguist, William Taylor – travelled throughout Europe and North Africa, lived in Russia and Spain and wrote passionately in support of minority languages and ways of life, most notably, Romani. In addition to world-changing writers, printers and publishers, Norwich produced the UK’s first provincial library in 1608 and the UK’s first provincial newspaper in 1701.

A brief stroll around 900 years of literary activity, yet many more writers and innovators – as many today as in the past – have drawn inspiration from a city where literature has been, and continues to be, the locus for change, experiment and contemplation.

Image: Elizabeth Fry

Subtle landscapes

Literature is a stealthy artform. Its strength lies beneath the surface of things. Poets and writers have always been attracted to Norfolk’s subtle landscapes, but the recent spate of superb ‘nature-writing’ to emerge from the region has been astonishing. Ronald Blythe, Richard Mabey, Mark Cocker, the late Roger Deakin, Robert Macfarlane; these are fine writers, deeply linked to each other and to the minutiae and universality of their environment.

The pioneering oral historian, George Ewart Evans (1909–1988), wrote the classic Ask the Fellows Who Cut the Hay and lived in South Norfolk.

Gresham’s School in North Norfolk produced WH Auden and Stephen Spender (as well as the composer, Benjamin Britten).

The comedian/writer, Stephen Fry, lives in West Norfolk.

Henry Rider Haggard (1856–1925) wrote King Solomon’s Mines from the family home in South Norfolk, a district that is also home to Bill Bryson.

Prize-winning biographers, Richard Holmes, Ann Thwaite, DJ Taylor and Kathryn Hughes, live and work on the outskirts of Norwich.

The county is also home to the award-winning Norfolk Children’s Book Centre and a remarkable number of leading children’s authors, including Rachel Anderson, Joyce and Polly Dunbar, Clare Jarrett, Pat Moon, Mal Peet and Kevin Crossley-Holland.

Many voices

The city’s reputation for dissent and free-thinking has bred a good-humoured tolerance and a strong creative temperament, but also a famous tendency, as expressed in the local dialect, to ‘du diffrunt’. From Boudicca’s rebellion against Rome in AD 61 to Saxon liberi homines (free men), the relationship between language, history and identity in this one small area of East Anglia is immensely complex. Wave upon wave of invaders wiped out the ancient Brythonic (British) language, raised common Latin to the higher status of the educated and ecclesiastical classes and – according to the distinguished Norwich linguist, Peter Trudgill – the Germanic tribes of the Angles, Saxons, Jutes and Frisians who founded the city gave birth to the English language itself.

Anglo-Norman and Hebrew poured into the melting-pot, spiced by the languages of the ships sailing down the Wensum bringing olive oil from Spain, dyes from Asia Minor, millstones from the Rhineland, Gascon wine, Scandinavian furs and Italian silk. Later still, the Dutch, Flemish and French-speaking Huguenots and Walloons, representing 37% of the local population, transformed Norwich into a trilingual city, with the addition of the Romani language in the 19th century.

Today, 108 languages and dialects are spoken in Norfolk and Norwich: a culmination over two millennia of the evolution of language in its many contexts, world events, social groups, narrative structures, personal stories, particular themes, stylistic variations and distinctive voices.

Today: A literary identity

The city’s literary identity has evolved through the constant flux and flow of ideas and styles that find physical expression in the remarkable fabric of the city. Norwich has 1,560 Grade I and II listed buildings including 32 mediaeval churches, many of which are used for arts and cultural purposes. This represents one of the largest portfolios of historic buildings in the country.

Norfolk would not be Norfolk without a church tower on the horizon or round a corner up a lane. We cannot spare a single Norfolk church. When a church has been pulled down the country seems empty or is like a necklace with a jewel missing.

Image © VisitNorwich

Discover more from Norwich UNESCO City of Literature