Thomas Heerma Van Voss is our virtual writer in residence for October 2020. He has published four works of fiction, including the novel Stern in 2013 (translated into German), and the short story collection The Third Person (2014). His journalism has appeared in De Volkskrant and NRC Handelsblad among others. He is one of the authors featured in the new Verzet series just out from Strangers Press.

Find out more about Thomas’ virtual residency here >>

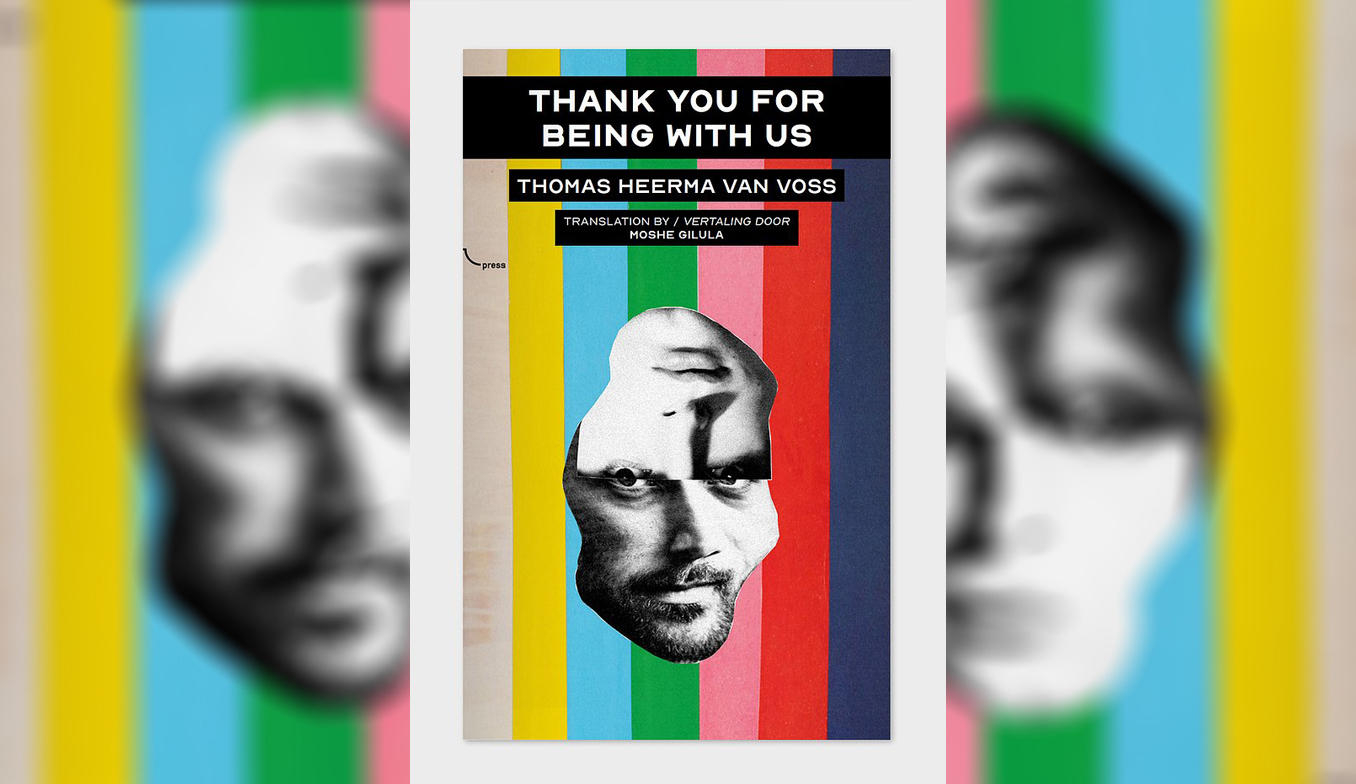

Thomas’s chapbook, Thank You For Being With Us, features two newly translated short stories selected from The Third Person. In one, a father and son, barely on speaking terms, meet for the first time in years in a television studio for a live broadcast to discuss a book the son has written about their failed relationship. Their artfully rendered alienations from and frustrations with each other speak of the widening generational gap we are all experiencing. In the other, a troubled voyeur watches from his window as people come and go from a local massage parlour while contemplating his life. These compelling, well-wrought characters draw the reader entertainingly into their strange and heart-breaking lives.

Here, Thomas introduces his chapbook, and shares his reflections on seeing the stories’ new life in English translation.

The Israeli author Etgar Keret once remarked that translators can best be compared to ninjas: if you notice them, they’re no good.

And indeed, nothing is as annoying as a literary text that retains tell-tale traces of the original language, combinations of words that you suspect may have a different or even multiple meanings in their original form. However, this belief – one that is shared by most writers and translators – does not answer the question: what makes a translation convincing? And how do you recognise a good translator?

I have had a number of my works translated, but always into languages that I at least partially understand (German, English, French). I enjoy being able to discuss the meaning of a specific passage with a translator and how best to interpret it, but it is always a strange experience when you see your own words in a different language for the first time. After all, the story is undeniably your own, built and shaped in the same way as you did yourself; the same length, the same tension. Nevertheless, a translation always feels somewhat distant because the words on the page are not written in your own language, the language in which you think and work. This is what makes a translation both remote and intimate, like hearing a stranger recounting a dream that you are sure only you could possibly have dreamt.

Moshe Gilula translated two of my short stories for my chapbook in the VERZET series and I experienced the same strange sensation when reading his translations. On the one hand I could never have written the prose on the page myself, but on the other hand I clearly recognised my own tone of voice, the story I had thought up, the characters I had created in my own mind.

At first I was slightly apprehensive about how my work would translate into English, especially the longer of the two stories that Gilula took on, which is also the title of the chapbook. Thank you for being with us is clearly situated in Amsterdam, with its street names and descriptions of locations. The main character, Egbert, a man who out of a combination of curiosity and sense of duty agrees to take part in a popular talk show along with his son, ends up in a TV studio that will sound instantly familiar to Dutch readers. That context is not available to most English readers, however. When I describe ‘Centraal Station’ – the name of the main train station in Amsterdam – in the story, I can immediately picture the place, the hustle and bustle, the roads and trams that wind their way around the building. Gilula translated it simply as ‘central station’ – a logical choice – but does a sentence like ‘The central station is cold and busy’ have the same impact as the original? And do the names of locations like Leidseplein and Westergasterrein conjure up the same images for the reader in English as they do in Dutch?

Probably not, but the more I immersed myself in Gilula’s translation, the less these questions seemed to matter. This was because in his English version he had managed to retain the compact and sometimes rigid tone that I had endeavoured to instil in the original, one I believed suited the main protagonists; in English, the story has the very same rhythm and tone. The more I read it, the more I thought: this is the most important thing a translation can set out to achieve. To recreate the same heartbeat, to stand alone while still adhering to Keret’s ninja analogy.

Of course, I could go on and on about the translation, about the craftsmanship involved and the more theoretical aspects. But this is neither the time nor the place to do that and I am probably not the right person for the job, either. I could also quote very liberally from Gilula’s excellent translation, but fragments without context are often left dangling in a vacuum, so the best option is to point interested readers towards the chapbook itself.

A more important consideration, in my opinion, is that the work of a writer does not finish as soon as the text has been printed. In a sense, every piece of text, be it a short story only half a page long or a full-blown saga, is always the starting point for a dialogue, for the question: how will the reader read it? An editor, a publisher, a translator, a complete unknown? Which images will the story conjure up for him or her? Will the same words affect different readers in different ways?

When someone translates your story it feels a bit like starting a conversation with a silent but attentive reader, the most perceptive kind out there. Hopefully the chapbooks published by Strangers Press will mark the start of many dialogues that will take us in directions none of us can predict.

Read an extract from Thank you for being with us

‘Egbert’s son had written a thesis on domestic violence. The thesis became a book, the book became a bestseller and Egbert’s son became an authority on dysfunctional families. Every time a teen mom loses it and poisons her child, a stressed-out househusband maims his wife or an unresponsive teenager stabs his parents, Koen is invited to appear on TV and explain, in carefully formulated sentences that everyone can understand, how such a thing could happen.

Egbert never intended to become a father. Children slobber and whine and demand constant attention, Marieke thought so too. So they took precautions. Condoms. The pill. Their doctor said: chances of pregnancy in such cases are less than 0.1%. Egbert still remembers the cold spring day, when Marieke and he heard those words. He’d insisted they go see the doctor. Just to be on the safe side. He remembers leaving the surgery in Amsterdam West, straightening his collar and thinking: why didn’t he just round it off to 0%? It’s such a negligible difference. Now he knows. Koen is living proof that less than 0.1% isn’t the same as 0%.’

Thank You For Being With Us was translated by Moshe Gilula. Thomas’s introduction was translated by Danny Guinan.

You can order the full set of VERZET chapbooks from the Strangers’ Press online shop

You may also like...

‘This is what we do, as translators: we keep listening and we keep adapting’

Cypriot writer Constantia Soteriou in conversation with translator Lina Protopapa

24th September 2020

Poetry Isn’t Lost In Translation, It Is Translation

Somrita Ganguly and Arunava Sinha share their experience of working together on the Emerging Translator Mentorship programme

31st August 2018