Interest in reading has been declining year-on-year in Japan and questions are being asked about how to bring books to people and enthuse the younger generation about writing. A key component of Japan’s literary landscape is a network of over 100 literature museums across the country, some focusing on the work of a single author, others exploring the literary heritage of a region, but as readers dwindle so audience figures are also down.

Kate Griffin is Associate Programme Director here at the National Centre for Writing, where she specialises in international working and literary translation. In preparation for a conference on the future of literature museums Kate set out to explore Japan’s literary heritage.

Don’t miss our Japan Now event in February featuring the launch of Kyōko Nakajima’s The Little House, the first of her novels published in English. She will be joined in conversation by Ginny Tapley Takemori, her translator, and Peggy Hughes.

The Tabata Memorial Museum of Writers and Artists is in the north of Tokyo, in a low, grey unassuming building overshadowed by an office block. In the early 20th century Tabata was a farming community but low rents and proximity to the Tokyo School of Fine Arts drew a number of artists to settle there. Writers started to join them after the leading Japanese author Akutagawa Ryunosuke moved there in 1914.

Other than one short English-language leaflet, all the information in the museum was in Japanese, so it didn’t take us long to look around. Parts I understood included a painting of Tabata back in its village days, photographs of the many artists and writers who lived there, and maps showing the location of their houses.

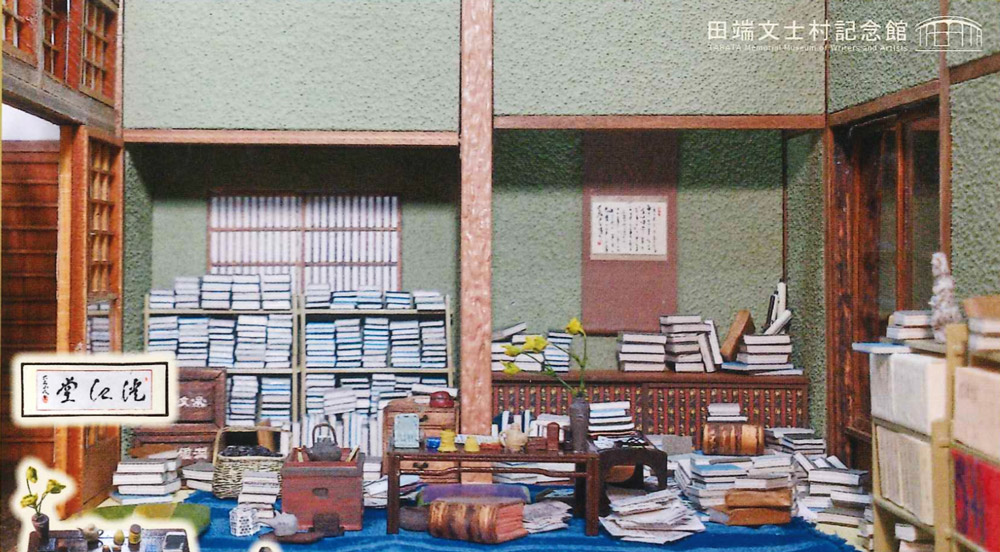

I was drawn to a screen in one corner showing a film about Akutagawa, combining black and white footage with old family photos and shots of a miniature recreation of his house, with a boy asleep on the floor by the garden, and a study crammed with books and papers. The model itself is on a table next to the screen, complete with tiny details of pens and brushes and tea pots. Akutagawa himself is up in a tree, which we see him climbing in the film to amuse his children.

In the next room were displays showing old family photos, letters, children’s drawings, books with hand-decorated covers and end papers, ceramics, bronze statues and textiles, including clothing belonging to one artist, along with his pipe and purse with a small ivory netsuke attached. Alongside photographs of buildings destroyed by the 1923 earthquake was a scroll painting of mountain peaks through clouds with planes flying in formation overhead, a reminder that more of Tabata was destroyed during a bombing raid in 1945.

Curious why Akutagawa had committed suicide in 1927 we looked up David Peace’s 2007 article in the Guardian and found a tale of inherited mental illness, debt and despair. I realised that the light-hearted film I’d seen of Akutagawa playing with his children had been made only months before he took a fatal overdose.

Next stop was the Ikenami Shotaro Memorial Museum, in a couple of rooms next to the busy Taito City public library. The museum itself was quiet, though. Local author Ikenami Shotaro wrote historical novels and period dramas about samurai in Edo Tokyo. The museum offered a map of Edo Tokyo showing the locations of his various novels, with present-day photos of the settings on the wall opposite.

At one end of the room was a recreation of Ikenami’s study, complete with the inevitable fountain pen, paint brushes and tea pot. On the desk on his bookshelf were his favourite brands of cigarette – Peace, Camel and Lucky Strike – and in all the photos he had a cigarette between his fingers or dangling from his lips. Alongside his books, paintings, sketches and scripts for theatre and cinema we were shown the accoutrements of the author’s daily life, from cat-shaped pipes to his hat, watches and collection of cassettes, including Fred Astaire.

Outside, I resisted the temptation to buy souvenir fans, tea towels, bookmarks, calendars or even masking tape illustrated by his animal sketches, but I did pick up a couple of postcards of his ink drawings of Edo Tokyo.

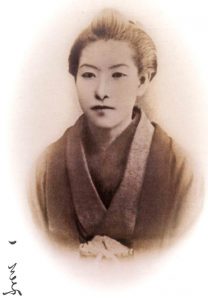

Our final stop was the Ichiyo Memorial Museum, in a quiet back street opposite a children’s playground. The museum is built on the site of the shophouse where Higuchi Ichiyo lived. At the time, her neighbourhood was very close to the Yoshiwara, where girls and young women from poor families were sold into prostitution. On the walls were ukiyo-e prints from that time showing the Yoshiwara milieu in which Higuchi’s stories were set.

Alongside recreations of her shophouse and the confectionary sold there we saw school photos, her kimono, and in one case a head from a kabuki play, though we weren’t quite sure of the connection there. Unlike Ikenami, her writing desk was small and plain. Next to it were her letters and poems on scrolls in the Hiragana running script that women used in those days as they weren’t taught the more sophisticated Chinese characters.

Although Higuchi died of tuberculosis in 1896 aged only 24, she published three novels, poetry and many other pieces. An English-language excerpt from one of her short stories on Ginzaline.

The conference on the future of literature museums took place on our final day in Tokyo, at the Museum of Modern Japanese Literature. The organiser, Yoshitaka Haba, runs a company called BACH, designing libraries and other literary spaces, including the library in the new Japan House in London. He was commissioned to reanimate the literature museum in Kinosaki, a town on the Sea of Japan coast famous for its hot springs (known as onsen). Kinosaki was devastated by an earthquake in 1925, and rebuilt in the old style, including the seven public baths. Nowadays it looks almost the same as it did in the 1930s.

The town entered literary history when the eminent Japanese writer Shiga Naoya started visiting Kinosaki from 1913 onwards, initially to recover from a train accident on the Yamanote line. After him, a lot of writers travelled to Kinosaki, escaping editors, lovers, their families. There are literary sites everywhere in the town, but local people were unaware of the history, so Haba was brought in to raise the literary profile. In the literature museum, it felt as though time had stopped, Haba said. His challenge was to update the museum and encourage contemporary writers to follow in the footsteps of their predecessors by staying in the Mikiya Hotel and writing about the place.

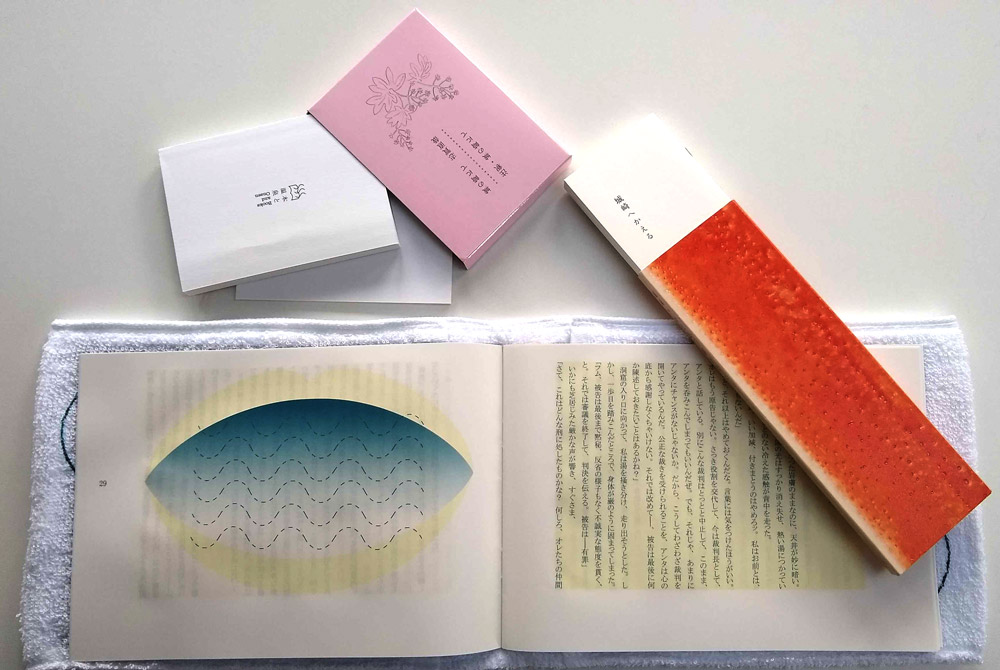

There are 72 hotels in Kinosaki, which has a population of 3,000. A number of young hotel owners contributed 50,000 yen each to form a non-profit called Books and Onsen, producing books about Kinosaki, and only available in the town, to lure people there. One of the books is made on special paper so that it can be read in the hot spring, with a towel as a cover. Another book, about eating crab, one of the main pastimes after the hot springs, has a cover that looks as though it’s made of crab shells. The third book is a small box set containing Shiga’s famous short story, At Kinosaki, with a second pamphlet of contextual notes, as times have changed so much since 1917 when the story was written. The books are available in the literature museum and many of the hotels; so far over 50,000 copies have been sold.

The following day we travelled with Yoshitaka Haba to Kinosaki, to see the place for ourselves. At Haneda airport, Haba and I went off to the Sakura Lounge to look at the library he curated for Japan Airlines. It used to be in a more public space but books started disappearing so now it’s behind locked glass. He chose books about Japanese design and traditional crafts; books about planes; a stewardess outfit and doll; JAL’s destinations and most famous passengers, from a panda to the Beatles.

After two short flights we arrived in Tajima airport, on top of a mountain, and drove to Kinosaki. The town was in a valley, surrounded by wooded mountainsides, colours by now tipping into autumn. There were canals and willows and the clack-clack of wooden clogs as we paraded around in our traditional yukatas heading for the onsen after our crab dinner. We sat in hot spring, outside even though it was late November, looking up at the waterfall and moon through the trees.

Next morning we went to Kinobun, the Kinosaki Literature Museum. From the start I could see the difference from the museums we’d visited in Tokyo. The entrance was welcoming, with a large quote from Shiga Naoya in English on the wall. The ticket desk was in an open space with a bookshop selling piles of Books and Onsen, next to a small café.

The special exhibition was about the journey from page to stage. The author Genichiro Takahashi had written a story about a memorial event for four modern Japanese authors – Futabatei Shimei (1864-1909), who brought the vernacular into literary Japanese; one of Japan’s most famous writers Natsume Soseki (1867-1916); Kitamura Tokoku (1868-1894) a spiritual writer concerned with matters of the soul who committed suicide; and the tanka poet Isikawa Takuboku (1886-1912). Life expectancy was quite short for writers (and everyone else) in those days.

The theatre director and artistic director of the Kinosaki International Arts Centre Hirata Oriza decided to make this story into a play. His theatre company came to Kinosaki for rehearsals and a performance at the KIAC. The exhibition documents this process through a photo diary, a long film of the dress rehearsal, stage props, even a photograph of the inside of Oriza’s suitcase. The display of books used for research included the poetry of Higuchi Ichiyo, whose museum we’d visited in Tokyo.

Another installation used animation projected onto a blank book lying on a desk to demonstrate the process of writing a play, from the story draft to script, ending with little stick figures acting out a scene. The story itself by Kenji Miyazawa, about two children in a train in the galaxy, would be familiar to most Japanese visitors.

Next to it hung a styrofoam sculpture of Chinese characters, carved by Haba himself in the museum’s back yard due to the limited budget. On our way upstairs we passed more styrofoam kanji, red this time, the characters for blood and death. During an exhibition dedicated to the crime writer Minato Kanae, visitors would find their way blocked by a mannequin lying with his head in a pool of cellophane blood.

In the gallery dedicated to Shiga Naoya, we found books, letters, scrolls, and a draft of his essay about Kinosaki. He set up a literary magazine which ran from 1913 to 1923, and encouraged a number of other writers to come to Kinosaki, resulting in cameo appearances for the town in quite a number of literary works.

As we left, the café was full of children in yellow caps listening intently to their teacher. Kinosaki is in a rural area and children often feel quite isolated, leading to low aspirations for their future. One of the aims of Kinobun is to introduce children to their literary heritage and also to writers – whether from Japan or other countries – who can inspire them to explore their own creativity.

Back at the Mikiya Hotel we were shown one of the rooms where Shiga Naoya stayed, with photos from that era and a postcard from Shiga to the current hotel owner’s grandfather. In the hotel lobby I found a small library curated, of course, by Haba, with books about books, from a collection of author photos to book design. The exception was an English language edition of Shiga’s short stories, including At Kinosaki, which, of course, I borrowed for the night.

‘I often walked on this road before supper. As I went up along the small, clear stream through the lonely autumn ravine in the chilly evening, my thoughts were often of unhappy things. They were lonely thoughts. But in them there was this nice quiet feeling.’

Thanks to the GB Sasakawa Foundation, Litstock and the Japan Cultural Agency for supporting this visit. We look forward to welcoming Yoshitaka Haba to Norwich in May 2019.