Associate Programme Director Kate Griffin and Japanese writer and translator David Karashima travelled to Dublin in the autumn to plan a symposium on literature museums with the Museum of Literature Ireland, the International Literature Festival Dublin and Dublin UNESCO City of Literature.

Along the way they encountered some of Dublin’s literary heritage and caught up on contemporary Irish writing.

Monday 14th October 2019

I’m in London, on my way to Dublin, so I visit the London Review Bookshop to stock up on Irish fiction for the journey. The bookseller and I are intrigued by Nobber, by Oisín Fagan. That evening, the night of the Booker Prize announcement, I sit in the Woolf & Whistle at the Tavistock Hotel, reading former Booker winner Anne Enright’s The Green Road.

Tuesday 15th October 2019

I’m travelling with David Karashima, who is in Norwich for a month, on sabbatical from Waseda University in Tokyo, where he teaches creative writing and literary translation. He is also involved in plans to set up an International House of Literature at Waseda, which will house the Haruki Murakami archive.

On board the Ulysses, we choose Leopold Bloom’s Snack Bar over the James Joyce Balcony Lounge as a quiet spot to read and look at the sea. As we disembark I try to take a photo of David in front of the James Joyce mural carved out of wood in the reception area but he won’t let me.

In the evening we meet up with Martin Colthorpe, director of the International Literature Festival Dublin and organiser of our visit. He has plans to introduce us to Dublin’s legendary literary pubs, as places of social and cultural importance. First we try Grogan’s but it’s too full of bohemians, artists and writers so we move onto Neary’s Bar, where it’s quieter and there are seats. We are served Guinness by waiters in white shirts and black bow ties. The regulars in their suits look as though they’ve been sitting in the pub for the past few decades.

Martin tells us that on his way to meet us he walked past a mural painted on the side of a house by Dublin artist Maser. It says simply Don’t Be Afraid, or Noli Timere in Latin, the words that Seamus Heaney texted to his wife shortly before he died.

Back in my hotel I notice a sign on the toilet seat: Sanctified for your protection. On closer inspection I realise that it is sanified, but prefer my first interpretation.

Wednesday 16 October 2019

We start the day with a meeting at the Museum of Literature Ireland, or MoLI, after James Joyce’s heroine. We are joined by Martin, Alison Lyons from Dublin UNESCO City of Literature and MoLI director Simon O’Connor, who shows us around the recently-opened museum. MoLI is based in UCD Newman House, a Georgian building that originally housed the catholic university founded by Cardinal John Henry Newman, who was canonised last weekend. Alumni include James Joyce, Flann O’Brien, Kate O’Brien and Maeve Binchy – all good pyschogeography for a literature museum, notes Simon.

‘The museum is spread over three houses, a maze of rooms and interlinking doors.’

It is an impressive space. We walk through mixed media exhibitions dedicated to literary activist and writer Kate O’Brien; maps and models tracing the footsteps of James Joyce’s Dublin; the River of Words, a digital and sound installation about language and word play; a display exploring the creation of the Free State and the development of publishing and censorship, including a report from the committee on evil literature; the Literary Cities section about Irish writers and their connections with Paris; and Irish Writing Now, showcasing contemporary writers.

MoLI is not a place you should visit in a hurry; the museum is full of soft furnishings and comfortable chairs to encourage people to sit and read and take their time. We pass a number of films, including a 15-minute version of Finnegan’s Wake, narrated by Paul Muldoon; clips of short story master Frank O’Connor; and an artist’s response to Ulysses. Upstairs there is a room dedicated to literary inspiration, with quotes, notepads and sound installations of Irish writers talking about what inspires them and their writing process.

The museum is spread over three houses, a maze of rooms and interlinking doors. After our tour, Simon takes us through a secret passage into the former classrooms that we hope to use for the symposium about literature museums we are planning together as part of the 2020 International Literature Festival Dublin.

Over lunch in the Commons café it’s no surprise to hear that Simon has a background in composition, given the number of sound installations we’ve heard, of writers reciting, reading and talking in the museum. He tells us about Radio MoLI, launched a few months before the museum opened, with its 24-hour digital broadcasting of Irish literary content ranging from commissions and plays to interviews and documentaries.

After lunch we visit the Reader’s Garden, planted to attract sound: white birches for moths to lure in songbirds; lavender for bees; ivy for the sound of rain falling on its leaves. Benches are surrounded by Irish yew hedging, which grows fast and in a couple of years will create reading snugs for sunny days. Some of the planting is inspired by Gerard Manley Hopkins, who taught at UCD and spent his last five years in a room in the building. We admire the ash tree in front of which James Joyce had his graduation photo, and the statue of a Jesuit priest with a book in his hand, who has stopped reading and is listening to the birds.

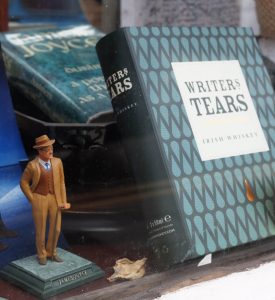

Our visit ends in the bookshop full of Irish writers, notebooks and a cushion printed with a portrait of James Joyce, the only one left as in the couple of weeks since the museum opened they have sold out. Simon shows us the first of the MoLI chapbooks, a series of reprints of old and hard to find Irish essays with new introductions or commissions. He gives us each a copy of The Day of the Rabblement, a student essay by James Joyce. I also buy two anthologies of Irish short stories: The Long Gaze Back, edited by Sinéad Gleeson and Being Various, edited by Lucy Caldwell.

‘Again, we find ourselves in a room full of voices…’

It is a sunny day, so Martin guides us through some of Dublin’s green spaces, past the impressive National Library and through the student and tourist-filled campus of Trinity College Dublin. He leaves us at Listen Now Again, the Seamus Heaney exhibition in the Bank of Ireland.

Again, we find ourselves in a room full of voices, of Seamus Heaney and others reading his poetry, starting with the man himself reciting Digging. It’s a very visual exhibition, with photos everywhere, of Heaney, his family and the landscapes that inspired him. There are piles of peat, displays of texts, letters and typewritten poems with handwritten corrections, digital snippets of his diaries and jottings, fragments of poetry and films. Although the exhibition is chronological, covering Heaney’s early life and works, his engagement with politics, and his later poetry, it is more of a response to his work, landscapes and influences, making you feel as though you’re inside his head.

Inevitably there is a bookshop tempting us with the complete works of Seamus Heaney, including the latest collection, 100 poems, compiled by his family after his death. David and I decide to start at the beginning, with Death of a Naturalist.

‘Dublin reminds me a little of Norwich, with its river, lanes and green spaces.’

We wander around the corner to the legendary Books Upstairs, where I find Rob Doyle’s short story collection this is the ritual, recommended by Simon. I’m struck by this passage:

‘Consider the name of this very ship, said John-Paul Finnegan. In fact, don’t even get me started on the name of this ship, he said. But it was too late, because he had already got himself started on the name of the ship, which was Ulysses. Not a single fucking dickhead in all of Ireland has actually read Ulysses, said John-Paul Finnegan. Except me, of course, the biggest dickhead of them all. Yet everyone in Ireland pretends to have read Ulysses, or acts like they’ve read it, but none of them have. The last person in Ireland to read Ulysses was James Joyce, and even he only read half of it, said John-Paul Finnegan.’

I have to admit that I haven’t read Ulysses either, but I leave the bookshop with a fine selection of contemporary Irish writing, according to the owner, including Mary Costello’s The River Capture, Anne Enright’s short stories and the latest issue of the Stinging Fly magazine. I head upstairs to the café and sit in the bay window reading and looking out at a sea of buses, the same bright yellow as the jacket of Nicole Flattery’s short story collection Show Them a Good Time.

On my way back to my hotel in Temple Bar, Dublin reminds me a little of Norwich, with its river, lanes and green spaces, a city made for walking. In the evening, we go to the Japanese Kitchen, for seared salmon sushi, and to Mulligans, for Ulysses and Guinness. I also buy a small tin of snuff, for no particular reason.

Thursday 17 October 2019

After a brisk walk across town, dodging coach-loads of children, I arrive early at the Trinity Centre for Literary and Cultural Translation, where David and I are meeting the director, Professor Michael Cronin, and Dr James Hadley, director of the MPhil in Literary Translation, who did his PhD at UEA. We sit surrounded by shelves of Irish literature in translation as Michael talks about what Stuart Hall calls vernacular cosmopolitanism, encountering otherness in the corner shop. The demographic in Ireland has changed significantly since the mid 1990s and the start of net inward migration, he tells us, so the Trinity Centre is finding ways to celebrate this cultural richness. We also talk about Irish heritage speakers in England, often congregating in Irish clubs and community centres. At the end of our meeting, James confesses to being a Japanese scholar, so he and David arrange to meet again in Tokyo in November.

David heads off in search of wifi and I duck into Sweny’s, the pharmacy where Leopold Bloom bought his lemon soap. The shelves are full of bottles of unknown pharmaceutical items alongside translations of Ulysses that are not for sale, though the random books on the counter are available for purchase. At the back of the shop, two people are poring over the book of prescriptions (they liked their valium in those days, apparently), while the owner, related to Beckett by marriage, serenades us with an Irish Gaelic song, accompanying himself on the guitar. I feel a fraud for not having read Ulysses, so I buy a postcard and some lemon soap and leave.

Around the corner is National Gallery of Ireland, where I spend an hour or so educating myself about Irish art, starting with the room dedicated to Jack B Yeats, younger brother of WB. A painting of Davy Byrne’s Pub, Dublin, from the Bailey (1941) by Harry Aaron Kernoff reminds me of the previous evening’s entertainment. I take a photo on my phone before noticing the crossed-out camera. In the bookshop I make amends by buying a postcard of the painting, as well as Dublin Streets: a Vendor of Books (1889) by Walter Frederick Osborne, though the booksellers on the banks of the Liffey have long since disappeared.

Before my next meeting I slip into the Dublin Writers Museum on Parnell Square, north of the river. The first two rooms have old-style displays tracing the history of Irish literature to the twentieth century, through text, photographs, letters and first editions. There are cabinets with Samuel Beckett’s telephone, a couple of typewriters, pairs of spectacles, even the odd death mask. Upstairs in the Gallery of Writers, a grand room with tall windows and a chandelier, the exhibition in progress explores the barriers to publication faced by women writers from Iris Murdoch to Edna O’Brien (August is a Wicked Month didn’t go down too well, apparently). In the annex at the back I find a room for children’s activities, deserted, and an empty exhibition room. The bookshop’s shelves are also sparsely populated; nonetheless I buy a substantial volume of Elizabeth Bowen’s short stories.

I’m a little bit late for my meeting across the road at Poetry Ireland, in a beautiful high-ceilinged room with a quote from Seamus Heaney over the fireplace. Director Maureen Kennelly tells us about their plans for renovation: as well as offering space for public events, the refurbished Georgian building will house their library of 30,000 volumes of poetry, which will include approximately 3,000 of Seamus Heaney’s Working Poetry Library, generously donated by his family. Tucked away at a desk in the stock room we meet poet in residence Catherine Ann Cullen, who will be running poetry workshops with disadvantaged communities in this part of the city, a striking mix of formerly grand buildings and rundown blocks of flats. Before we leave, Maureen gives us each a copy of their own publication, Poetry Ireland Review.

‘I’m reminded of Dragon Hall and the hundreds of people who were born, lived and died in our building’

Back across the road we drop by the Irish Writers Centre for an impromptu meeting in their library and café space where you can get tea and biscuits for one euro. Acting Director Hilary Copeland and her colleague Kiki Drost tell us about the different types of residencies that they run, some offering time and space to write at various retreats, others involving workshops with community groups who wouldn’t otherwise access the centre’s courses. I like the idea of their roaming residency, sending writers off on the train around Ireland to run workshops in universities.

Next Martin takes us to the museum at 14 Henrietta Street, but we’re just too late to join the last guided tour of the day. At one point, this four-storey Georgian townhouse turned tenement housed 17 families, leaving a legacy of stories. I’m reminded of Dragon Hall and the hundreds of people who were born, lived and died in our building, and resolve to visit again next time I’m in Dublin. In the meantime I buy a beautiful book of poetry and photography, Museum, by Dragana Jurišić and Paula Meehan.

As we leave it starts to rain, the clouds grey as the skies in an 18th century painting of Dublin Bay in the National Gallery. I take refuge in the Gallery of Photography Ireland, and peruse their exhibition A Modern Eye – Helen Hooker O’Malley’s Ireland, the photographer’s vision of post-Independence Ireland. I’m too late to visit the other half of the exhibition, in the Photographic Archive across the square, so I buy the book instead.

On my way back to the hotel I can’t resist the Gutter Bookshop, where I pick up A Line Made By Walking, the new novel by Sara Baume, who’s going to Tokyo for a literature festival next month. Back in my hotel room, I’m slightly panicked by the number of books I’ve bought over the past couple of days, and the corresponding weight of my snuff-scented suitcase.

Martin, David and I spend the evening in James Toners, the literariness of the pub evidenced by the portrait of James Joyce above the bar.

Friday 18 November 2019

The morning starts unfeasibly early as David and I are on the 8am ferry. I write up this blog in Leopold Bloom’s bar, on the good ship Ulysses that no-one has read.

Explore Dublin UNESCO City of Literature using Kate’s travel diary as your guide. See below a full list of the fantastic books mentioned along the way:

Reading list

- A Line Made By Walking, by Sara Baume

- Poetry Ireland Review, edited by Eavan Boland

- Collected Stories, by Elizabeth Bowen

- August is a Wicked Month, by Edna O’Brien

- Being Various, edited by Lucy Caldwell

- The River Capture, by Mary Costello

- this is the ritual, by Rob Doyle

- The Green Road, by Anne Enright

- Yesterday’s Weather, by Anne Enright

- Nobber, by Oisín Fagan

- Show Them A Good Time, by Nicole Flattery

- The Long Gaze Back, edited by Sinéad Gleeson

- Death of a Naturalist, by Seamus Heaney

- 100 poems, by Seamus Heaney

- The Day of the Rabblement, by James Joyce

- Museum, by Dragana Jurišić and Paula Meehan

- The Stinging Fly, edited by Declan Meade

- A Modern Eye, Helen Hooker O’Malley’s Ireland